The words ‘Black Death’ or ‘bubonic plague’ usually conjures up a reverence with feelings of dread and, for most Europeans, the images that accompanied nursery rhymes and stories we were taught as children: the doctors wearing those sinister bird-like masks, both iconic and terrifying; the crosses painted on doors to ward away visitors from homes already infected; and the horse-driven carts loaded with putrid corpses and the unassailable stench that followed them.

Killed every third person

While ‘The Great Plague’ that ravaged London in the 17th century, quelled by the Great Fire in 1666, is very well documented in the English language, a further outbreak in the following century on Danish soil is less so. Records suggest that as much as a third of Copenhagen’s population was wiped out by the devastating disease.

Likely to have started in China, the bacillus (Yersinia pestis) bacterium, and the subsequent Black Death that it brings, quickly took hold in many European countries during the 14th century.

At that time, Scandinavia was one of the last places for the sickness to reach due to the disease being spread from the south: from great trading ports like Constantinople and along the established shipping routes of Europe’s south coast. Thereafter periods of containment and resurgence prevailed across the continent over the next 400 years.

A resurgence in Sweden

As early as 1710, reports came of one such resurgence in Sweden – it was quickly confirmed that Stockholm had fallen prey to the sickness. At that time the Great Northern War (1700-21) was raging, and Denmark was part of an alliance fighting against the Swedish Empire. With Denmark’s borders closed and guarded, the authorities were confident that the disease would not reach Denmark. Therefore, they were quite unprepared when it did just that.

Reports suggest that the disease arrived at the port of Helsingør and entered the capital via the postal routes. The speed of the spread of the highly contagious disease, carried by rodents and fleas, was literally breathtaking. The incubation period is a matter of days (between two and eight) during which fever, vomiting and lesions give way to death.

Taking hold in the capital

By the last week of June 1711, there was a sharp rise in mortality and the state only then began issuing precautions to be taken against the plague. Many citizens were fleeing the now heavily-affected region around Helsingør, and the state has quick to advise Copenhagen’s population against misplaced charity towards those potentially infected. Those who did not comply with their precautions were punished, and particular severity reserved for those who did not bury their dead immediately – the state was adamant there was not time for a service or ceremony.

A priest was assigned the unenviable task of serving the city’s plague-stricken. For the following year that priest commandeered a former military grounds at Wodrofsgård. It was here that the disease was treated and would hopefully be contained. Some days after the priest’s appointment, a health commission was also set in place.

Perks of being rich

Many began to flee the city. King Frederick IV was already in Jutland, and soon the remaining members of the royal family followed. Government officials remained until August before retreating to Jægersborg.

The east side of the city was cut off by police so they could better monitor the flow of incoming and outgoing traffic. A total of 90 officers were assigned to handle the containment of the sick houses. The wealthiest were allowed to flee to their residences outside the city, but most of the poor had nowhere else to go. Many were even forced to stay against their will.

As one might expect, there were mass lootings of the abandoned houses across the city, but the main problems facing those containing the disease were avoiding infection themselves, the impossibility of burying the vast numbers of dead, and finding those willing to treat the sick.

Problem finding nurses

Nurses were of increasingly short supply, and so a unique arrangement was reached. Those treated who had survived the disease, thereby having developed immunity, should then themselves serve in the hospital for a period of no less than one month.

However reasonable this may seem, many evaded the duty by running away. Even some of the trained staff resented the risk of treating the sick and became negligent and careless in their duties. Some would turn to alcohol to carry out their work, leading to many clashes with their superiors, and there are even accounts of hospital staff stealing the belongings of the patients.

Corpses aplenty, but too few coffins

With regard to the dead themselves, the number of bodies grew overwhelmingly. The stench was so strong as to be paralysing, and worse still, they remained highly contagious. It was decreed to be imperative that corpses should be disposed of within 24 hours of death to minimise the risk to others, but of course, this was impossible to enforce.

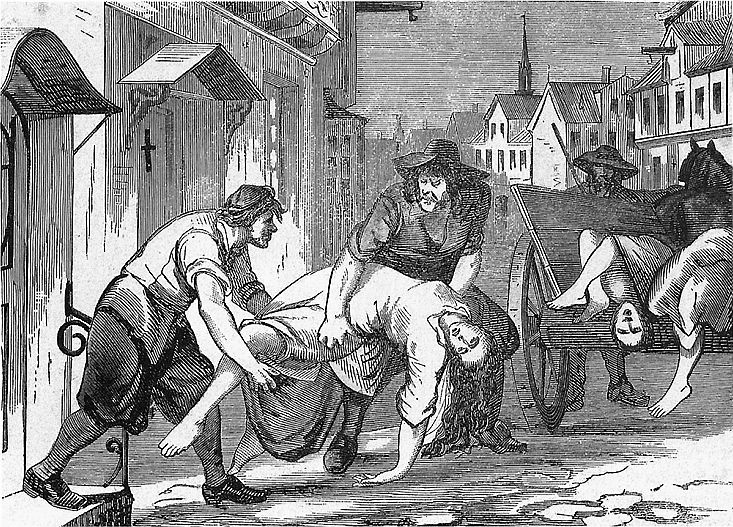

Furthermore, even for those few who could afford one, there was a shortage of coffins (and coffin makers) – so much so that it took at least a day to track one down. In many cases, corpses would be left in the clothes they died in, wrapped in the sheets from their beds, and left for collection by the so-called ‘stink wagons’ (lugte-vogne).

The highly contagious nature of the corpses required that they be buried at least six feet deep. This required man power of a large scale, the likes of which was unachievable at that time. Recognising the measures required, the military (still at war) donated 200 soldiers to do the digging on the condition that members of the Copenhagen bourgeoisie filled their vacant posts. By late August, thanks to co-operative initiatives like this one, the scales began to tip in the favour of the health commission battling to contain and stop the outbreak.

Containment and rehabilitation

It was this commission, led by one Johan Eichel and composed of prominent members of both the civil and military services, which oversaw the containment and rehabilitation of Copenhagen. Gathering twice a day at the town hall, reports were heard and decisions made. The decisions were then executed by a growing team of volunteers: priests, doctors, diggers, barbers and watchmen.

Although the outbreak was not fully contained (reports of new infections were still coming in from Roskilde by late August) and an estimated 23,000 lives were lost, it seems the Danish penchant for holding meetings is well founded and contributed considerably to their victory here. This was the last time that den sorte død visited Danish shores.