From humble beginnings in the town of Ribe on Jutland’s west coast to being called the ‘ideal American’ by President Theodore Roosevelt, Jacob Riis was a Danish immigrant to America who brought about social change through a mixture of police reporting, journalism and documentary photography.

However, had the disapproving father of Riis’s childhood sweetheart not rejected the young carpenter as being unsuitable marriage material, making the young Riis determined to get as far away from Denmark as possible, it is likely that the Dane’s influential career as photographer and social reformer would have never happened at all.

Shunned and armed

Born on 3 May 1849 in Ribe as the third of 14 children, Riis’s upbringing in Denmark was typical of the time.

After his initial schooling he trained as a carpenter in Copenhagen before returning to his hometown in the hope of marrying his longtime childhood girlfriend.

His subsequent rejection by her father, mixed with a general lack of work at the time, meant that in 1870, at the age of 21, he decided to head to America to find his fortune.

Arriving in a New York that was burgeoning with new immigrants, Riis noted that the city was far from being the civilized place that Copenhagen was, and he recounted in his autobiography that one of the first things he did when he arrived in the city was to follow the “custom of the country” – which he did by immediately buying himself the largest revolver he could find.

Journalism politicizes

Times were tough over the first five years for Riis who wandered from place to place doing whatever work he could find, including stints in mining, building, bricklaying and farm work.

It wasn’t until 1877 that he found his true calling when he started working as a police reporter for the New York Tribune newspaper.

In his book ‘The Making of an American’ he described his new job as ‘‘one that gathers and handles all the news that means trouble to someone: the murders, fires, suicides, robberies, and all that sort, before it gets into court’’.

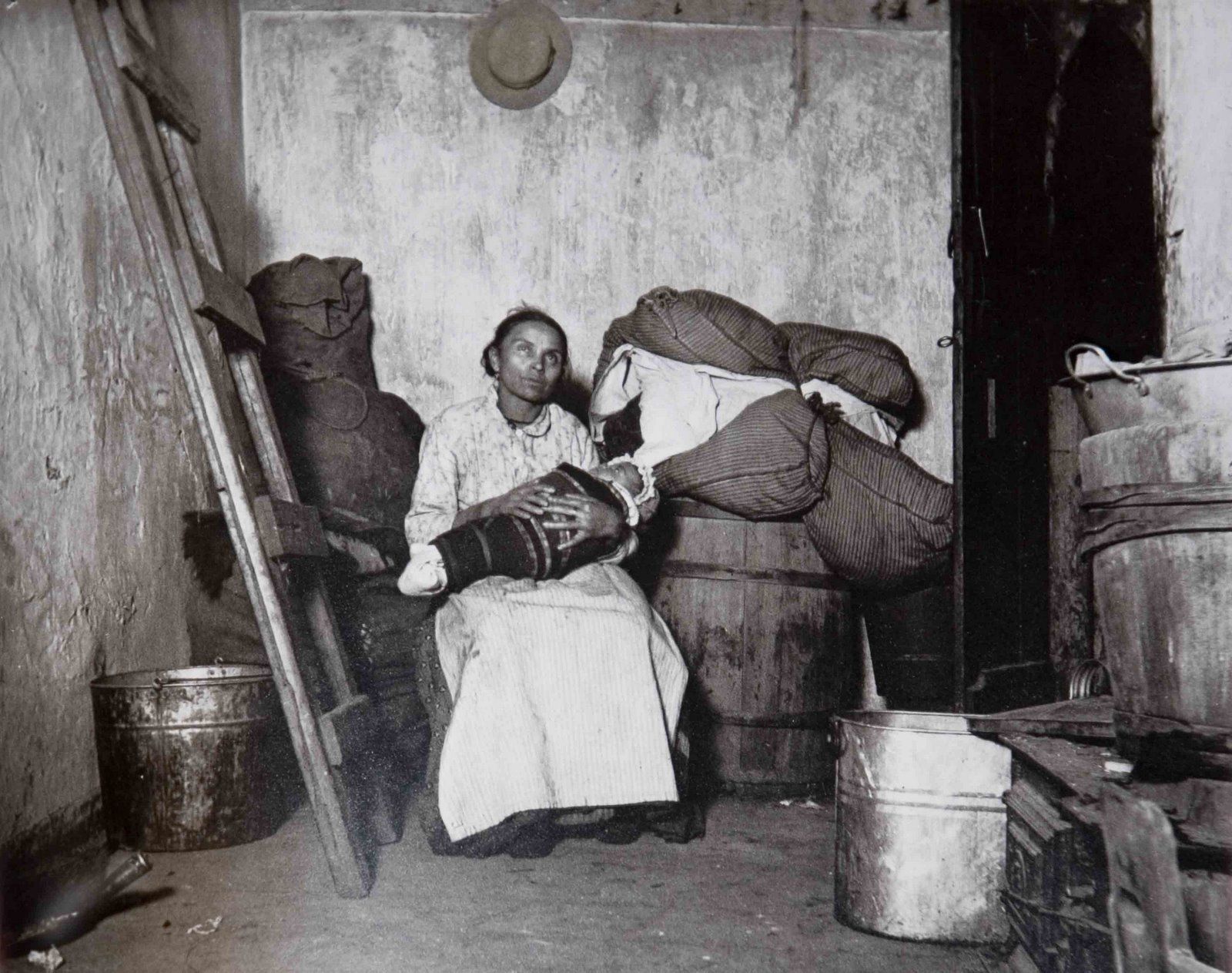

It was through this work that Riis first experienced the city’s slums and tenements – the overcrowded buildings filled with mainly new immigrants living in squalour and abject poverty, and where typhus, cholera and tuberculosis ran rife.

As an immigrant himself, Riis not only sympathised with those living there, but eventually started to shift his focus from merely reporting what was going on to searching for an understanding of the causes of the problems.

Riis questioned the link between the poverty of recent immigrants and the role that environment played in that poverty, and he would go to become a major campaigner for housing reform.

The most useful citizen of New York

In an article he wrote for the New York Tribune, Riis argued that “it is not the squalid people that make the squalid houses, but the squalid houses that make the squalid people.”

He called for better housing, adequate lighting and sanitation, and the construction of city parks and playgrounds.

It was through his enthusiastic campaigning that he met the then police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt.

The two became good friends and the future president would later call Riis “the most useful citizen of New York” for his social work.

Visual impact

As well as the numerous amounts of newspaper articles he published, his quest for social reform saw him author a number of books, the most famous of which is entitled ‘How the Other Half Live’’, and he also toured and gave regular talks and lectures on the subject.

It was during these lectures that he started employing photography as a tool to help give middle and upper class New Yorkers an insight into the shadowy underbelly of the city and to help prove his claims of the misery and poverty existent there.

In those days lenses were slow and required long exposures and ample light, but Riis experimented with recently-invented magnesium flash photography and for the very first time recorded the darkest corners of this seldom-seen world on his glass plate negatives.

Treasures on the attic

Despite describing himself as ‘’no good as a photographer’’, Riis is now acknowledged as a pioneer of documentary photography and has gone down in the history of the genre for the role he played in its development.

However it wasn’t until the 1940s, 30 years after his death, that his skill as a photographer was really acknowledged.

After stumbling across an old book of Riis’s photos in a second hand shop, photographer and historian Alexander Alland decided to track down the original negatives.

However, despite the meticulous care Riis took archiving his written work, the same couldn’t be said about his photos.

Eventually Alland persuaded Riis’s oldest son to search the attic of the family house where he came across a collection of glass plate negatives and glass lantern slides.

From these original negatives, Alland made high quality exhibition prints that would be viewed on museum walls all over the world over the remainder of the century.

Many of these photos now hang on the walls of the Museum of the City of New York and play testament not only to the role that Riis played in the evolution of photography, but also the role that this Danish immigrant played in the history of social reform in America.