Ask the average Dane to name a major international company from their homeland and they would probably quickly jump to Carlsberg or Maersk. Perhaps they’d stretch to Bang & Olufsen or Novo Nordisk, but it’s likely that few would name Haldor Topsøe.

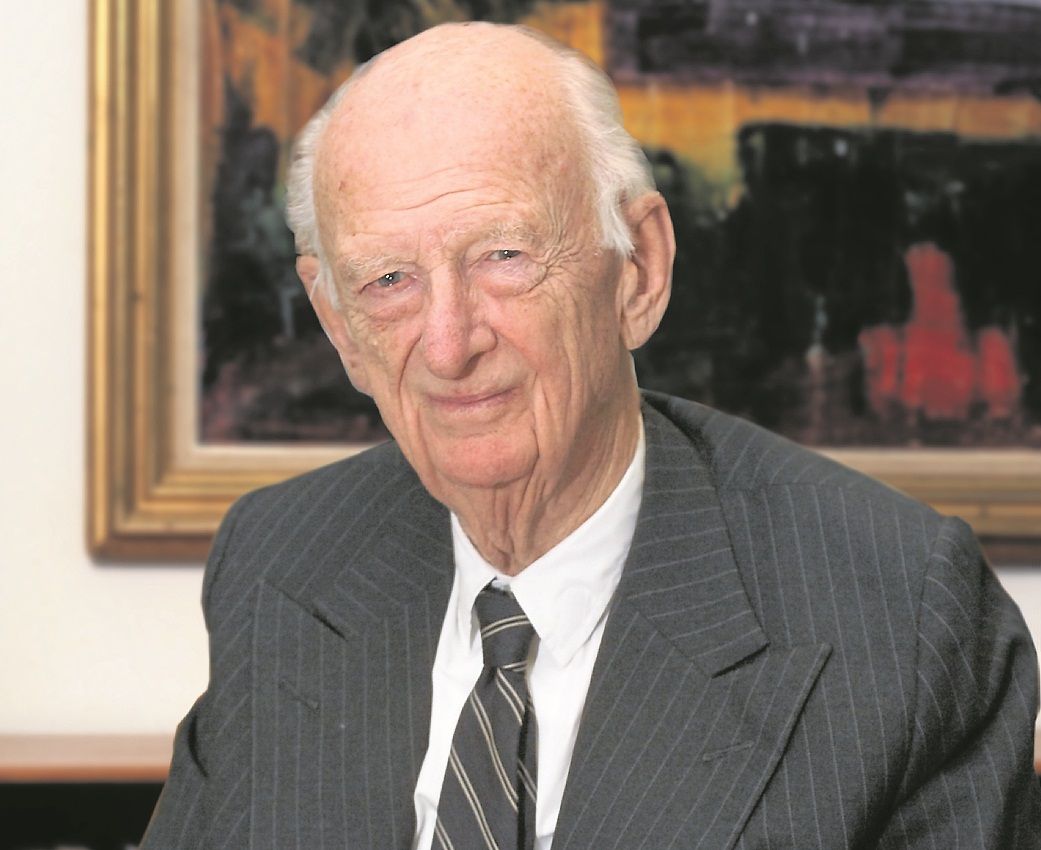

Or that would have been the case up until 20 May 2013. Because on that day its 99-year-old founder, Haldor Topsøe, finally shuffled off his mortal coil. His death grabbed headlines for two reasons. Firstly, there was his extraodinary career to consider in which he founded a firm that went on to become the global leader in its field (chemical engineering, and specifically the development and manufacture of catalysts). And secondly, there was the timing. Topsøe died four days short of his 100th birthday, which saw the media’s milestone tributes swiftly become obituaries.

Like his father, a captain, but of industry

Still an active chairman of his company’s board, Topsøe’s distinguished career had seen him play a pioneering role in an industry that is now essential to modern society, in which he put into practice his admirable personal beliefs every step of the way.

Much of the development of the company was driven by Topsøe’s devotion to welfare. He is quoted as saying that “the corporate world itself means nothing unless it improves the lives of people and the conditions in poor countries”, and no doubt this feeling of social responsibility was passed down from his father. Born in Copenhagen on 24 May 1913, Topsøe was the eldest son of Captain Flemming Topsøe and Hedvig Sofie. During the social unrest that Denmark faced in the 1920s, Captain Topsøe was involved in voluntary social work, including the provision of vital services during general strikes, and his actions encouraged his young son to look beyond social boundaries in his future career.

Changing occupations

The direction of that career was set during the 1930s when Topsøe studied physics under the renowned physicist, Niels Bohr, and chemical engineering at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU). In 1936 he began work as a chemical engineer at Aarhus Oliefabrik, choosing to enter employment rather than continue his studies and secure his doctorate. However, shortly afterwards, he turned down a central role in developing his employer’s research centre and left after three years to start his own business.

His plans hit an immediate obstacle though. Topsøe, his wife Inger and their young family were due to leave for the US in April 1940 as part of his new business plans, but Germany began its occupation of Denmark on the same day as their planned departure. Returning to his studies was not an option during the Occupation, so Topsøe turned this setback to his advantage and made the decision with his wife to start his own company in Denmark, based on his background in chemical engineering.

The catalyst within

Haldor Topsøe was founded in April 1940 with Topsøe’s belief that catalysis (the process of increasing the rate and efficiency of a chemical reaction by introducing a catalyst) could bring great benefit to industry worldwide. It proved to be a self-fulfilling prophecy, and today catalysis plays a key role in 90 percent of the world’s chemical processes and is used in everything from the processing of food to the manufacturing of fuel. Haldor Topsøe celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2015, and there can be no doubt as to the central role this Danish firm has played in the development of its own industry.

Throughout that long history, Topsøe has remained at the forefront of the industry as well as the company he founded – in 2007 the Topsøe family regained sole ownership of their company after 35 years of co-ownership with the Italian Snamprogetti Group. Right up until his death, the chairman still regularly attended meetings alongside his son, Henrik Topsøe, who served as the company’s executive vice president.

Engineer of the century

The company’s progress throughout its first 20 years included several industrial world-firsts as it constantly sought to increase the value of catalysis as an industrial process, and expansion followed with the opening of a US subsidiary. During the late 1960s, its founder’s vision was recognised with two honorary doctorates, from Aarhus University in 1968 and DTU in 1969. Those two honours were the first of many.

A third honorary doctorate came in 1986 from Chalmers University during the same decade that saw Topsøe receive a Gold Medal from the Royal Academy of Sciences and the Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur, the highest decoration in France. In 1999, Ingeniøren magazine named him ’Engineer of the Century’, and in 2008 Haldor Topsøe was made a Knight of the Grand Cross of the Dannebrog Order, complete with a Topsøe crest that features a silver methane molecule to symbolise his work with catalysis.

Today, more than 75 years after its foundation, and with the company’s main manufacturing plant and headquarters both still in Zealand, Haldor Topsøe conducts its business around the world and employs nearly 2,500 people. In addition to its range of catalysts and chemicals designed to make processes more efficient and products cheaper, its research efforts also include advancements in areas such as air pollution control and alternative fuels.

A top place to work

For all of this, and fittingly for the story of his life, Topsøe himself was undoubtedly the most important catalyst in his company’s repertoire. As significant as his scientific knowledge or economic and business acumen was his ongoing ability to build and grow a global Danish company that is still thriving. Of course, putting all of this down to one man would be a step too far, and Topsøe himself would have agreed with that.

Instead of any individual achievements, Topsøe cited the nurturing of talented, dedicated colleagues, and the provision of a “great place to work” as one of his main accomplishments. He received the Hoover Medal, an American engineering prize, in 1991 for his “involvement with leaders in Third World countries, which have significantly contributed to an increase in world food production through technology transfer”. As modest as he was brilliant, he said at the time: “I can only allow myself to boast a little because it is the result of my colleagues’ work.”

While Topsøe didn’t quite see his century through, for a long time to come, his achievements over his 100 years will be a challenge for most other captains of industry to match, in Denmark or anywhere else in the world.