Lord Palmerston, a former British prime minister, turned the Schleswig Holstein Question into a joke with his anecdote about how he was one of only three people to ever understand it – the other two being long dead or in a loony asylum.

What he neglected to add was that his monarch, Queen Victoria – along with leading members of the British and Danish governments and aristocracies – was complicit in an enormous cover-up to stop the duchies falling into German hands, thus giving it an Atlantic coastline.

READ MORE: How the bloodline of Frederik VII, the childless king, lives on

The lost princess

The ploy failed. Schleswig-Holstein, the southern part of the Jutland peninsula, became part of Germany in 1864, bringing with it the north Atlantic coastline the blossoming superpower so dearly coveted.

But the cover-up remained unexposed until a chance discovery over 100 years later by a British woman delving into her family history in Wales – a quest that eventually brought Irene Lewis Ward to Denmark.

Irene’s findings will astound royals and historians on both sides of the North Sea because they prove she is the granddaughter of a legitimate daughter of King Frederik VII, the last of the Oldenburg dynasty, who died apparently heirless in 1863.

Exiled to save the duchies

Irene’s grandmother Elizabeth Lewis nee Wynn was the daughter of Frederik and his third wife, Louise Rasmussen, a commoner who took the title Countess Danner. It is commonly perceived Danner only had one child – a son from an earlier relationship – but she actually had two.

Her daughter was born in great secrecy in February 1851. She was initially named Mary.

Had she been a boy, he would have been joyously announced to the nation and confirmed as Frederik’s heir and successor to his monarchy and dukedoms. Although the royal couple’s marriage on 7 August 1850 was morganatic and their offspring had no automatic right to succeed, the ‘Constitution Giver’ was a popular king and there would have been no opposition in Denmark or the duchies.

But as a girl, there was a big problem. In Denmark, it was perhaps solvable, but in the duchies, it was insurmountable. Their Salic succession laws prohibited the entire female line from inheriting. The situation was so perilous that the very knowledge of a female heir’s existence would have resulted in a German-assisted revolt and the monarchy losing the duchies forever. As far as Denmark and Britain were concerned, this needed to be averted at all costs.

A helping hand

The infant girl’s swift exile was handled by the then British ambassador, Sir Henry Watkin Williams-Wynn, who served in Copenhagen from 1824 to 1853. It is interesting to note that on 1 March 1851, just one day before Elizabeth’s official birthday, Queen Victoria made the already knighted diplomat a Knight Commander of the British Empire.

The Wynn family found Elizabeth a home with a widowed retainer of the family’s vicar, whose surname was also Wynn, and set them and the widow’s parents up as the owners of a new inn. And so it came to pass, that the daughter of the king of Denmark was brought up in a Welsh pub.

The young squire

All of this would have stayed buried in the past had Irene Lewis Ward, who is now 87, not been intrigued to find out who her grandmother was – a family mystery that hung like a shadow over her father’s life up until his death in 1958. It saddened and frustrated my father throughout the whole of his life,” explained Irene. “Who was his mother and where are his maternal relatives?”

Orphaned at the age of six, he had naturally assumed his father’s side of the family would fill in the blanks, but they knew next to nothing. Instead it was a return to where his mother lived and a chance encounter with an old man who called him “the young squire”, which in hindsight to Irene was a reference to the rumours about her grandmother’s noble parentage.

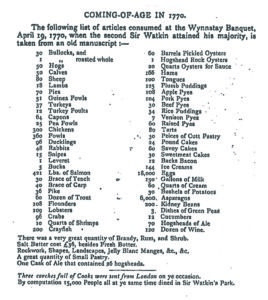

The old man recalled going to one of the Williams-Wynn’s wedding feasts when he was just eight years old at which thousands of people were present. But the young squire was sceptical, as was his daughter at the start of her investigations.

“I could not imagine that gentry would have allowed any Tom, Dick or Harry to dine at their boards,” said Irene.

“Like my parents, I had not given the old man’s words much thought and, indeed, suspected he had been in his dotage.”

A ten-year odyssey

But when Ward discovered evidence that the Williams-Wynn wedding feasts of the time were attended by up to 15,000 people, she changed her tune and started to look into the family’s affairs.

The possibility that her grandmother was the illegitimate offspring of nobility suddenly looked plausible. Little did she know then that she would discover she was descended from royalty and legitimate to boot!

In total, it took Irene and her husband, Bob, ten years of sleuthing in rural north Wales between 1969 and 1979 to unravel the truth.

The closer they got, the more they sensed their research was being impeded.

“One would have thought that sufficient time had passed for it to have no significance now,” she said.

“But on several occasions, during our research, we were aware of the shutters being closed against us.”

Finally revealing all

Irene has spent the best part of three decades writing two books on the subject.

‘The Price of Peace – A Conspiracy of Silence’ (available from lulu.com and Amazon) is a work of fiction based on the historical facts of the cover-up and was released on August 4 as an e-book.

“It is written as a historical novel based firmly upon facts, rather than as a non-fictional work, because I didn’t feel comfortable about putting words into the mouths of – or allocating personalities to – people I had never known,” she revealed.

“It follows my Danish grandmother’s life, from cradle to grave, before revealing her birth parents and the reasons for her exile. While I have allowed imagination, hypothesis and family folk-lore to colour the canvas, no dates have been altered and no known facts changed or ignored.”

The second book, ‘Piece by Piece – a Genealogical Jigsaw’, is a factual account of her quest to uncover the truth. It is due to be released later this year.

Like a princess

Soon after her discovery of who her grandmother was, Irene visited Jægerpris to pay her respects at her great-grandmother’s tomb – an experience she remembers as “very moving”.

It was her first visit to a country that she could, in a parallel universe, have been queen of. After all, it is by such fine lines that royal dynasties rise and fall.

As a child, Irene knew little about Denmark – only parts of its shared history with Britain and Hans Christian Andersen.

“I loved his fairy stories as a child, except when my big brother used to tease me and say that I was like ‘The Princess and the Pea’ because I was so sensitive,” she recalled.

Turns out she was more like the princess than he could ever have imagined.