The Danes arrived a little late to the colonial party in the West Indies during the European expansion into the Americas, and by the time they first settled on the Caribbean island of St Thomas in early 1672, many European nations had booming trades on nearby islands and in North American colonies.

First the Scandis, then the slaves

These pre-existing economies facilitated Danish growth in the area by virtue of the well-known ‘Triangle Trade’ – the route of cargo from America to Europe, Europe to Africa, and from Africa back to the Americas. While commodities such as sugar and cotton were sent to Europe for profit, it was the cargo that came west that drove the entire venture: slaves.

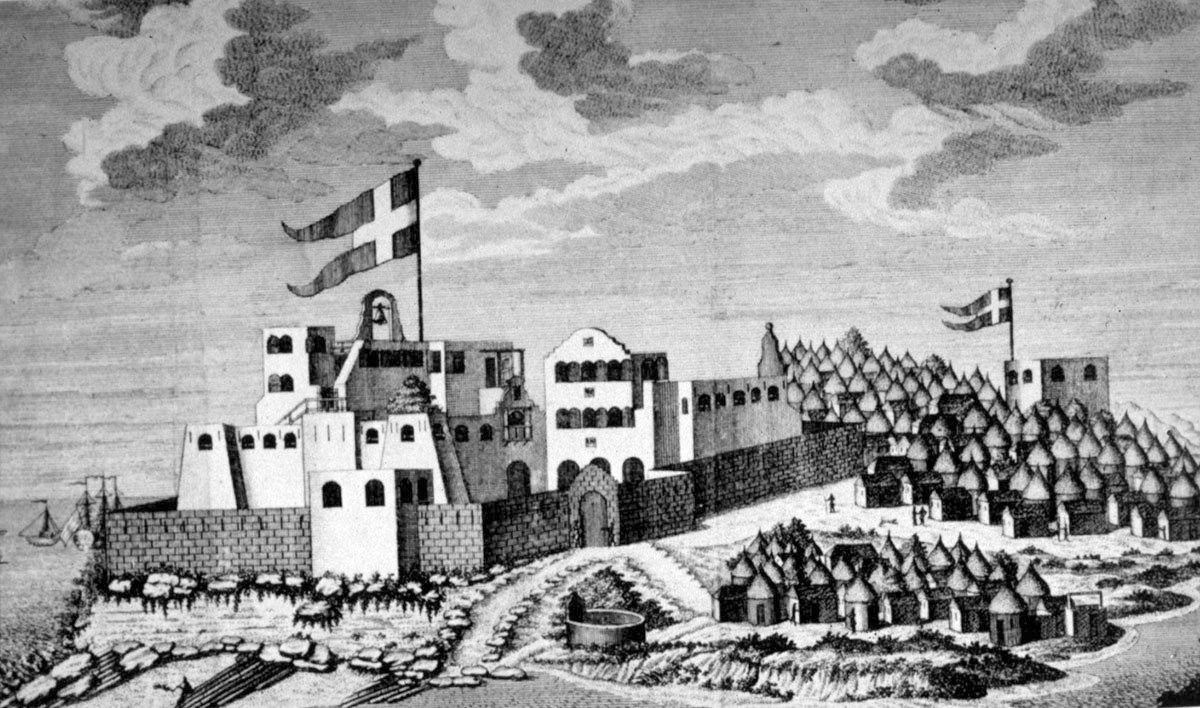

The first Danish mission to the colonies was an arduous one, leaving just 29 survivors to settle on the island of St Thomas. A year after its establishment, the first ship bearing African ‘cargo’ arrived, bringing 103 slaves to the colony and immediately establishing a slave-majority population.

Heavily outnumbered

As St Thomas developed into a prospering economy thanks to the labour of the slaves, producing sugar, cotton, indigo and tobacco, the Danish West India and Guinea Company laid claim to the island of St John in 1684, expanding their colonial presence. But that didn’t necessarily mean more Danish settlers: in 1688, 338 white inhabitants populated St Thomas along with 392 slaves.

In 1724, when St Thomas opened its harbour to ships flying the flags of most western European countries, the Danish economy and the slave population that drove it reached a new high. On St Thomas in 1725, there were 4,490 slaves and only 324 white inhabitants. The island of St John had a similarly disproportionate number of slaves to non-slaves. In 1733, it’s estimated that the island had nearly 1,100 slaves and only 200 non-slaves.

All roads to Accra

The Danish colonies imported their slaves from just one place: Accra, a port town along the southern Guinean coast in modern-day Ghana. When the Danes first entered the slave trade in 1657, the port was owned and operated by the Accra tribe. The Accra tribe used another tribe, the Akwamu, to facilitate the flow of merchandise to the port from inland Africa through trails in the forests and jungles. It was an arrangement that was ultimately going to prove costly for Danish operations.

The Akwamu, notoriously skilled warriors, demanded a part of the profit being made by the Accra tribe as an allowance for passage through their tribe’s territory. When they were denied, they allied with the Accra’s neighbouring tribes and eventually led a successful attack in 1677, conquering the Accra tribe and becoming the dominant tribe in Accra and along the ‘slave coast’ of Africa.

Not your typical subservient

But the Akwamu abused their power, mistreating those they conquered, and eventually faced a rebellion themselves. When they were defeated in 1730, thousands of Akwamu men, women, and children – citizens of a tribe whose members considered themselves to be warriors and nobles – were sold into slavery at the Danish fort in Christiansborg and put on ships to St Thomas and St John.

In 1733, approximately 150 slaves – all Akwamu tribesmen and women – staged a rebellion on the island of St John. The slaves, who outnumbered colonists at a rate of nearly 5:1, assumed control of the fort at St John’s Coral Bay and proceeded to take possession of many of the plantations through violent means, often killing the white plantation owners.

An Akwamu wake-up call

Although French and Swiss ships arrived from nearby islands to help Danish forces end the rebellion, the success of the slaves gave Danish authorities an obvious wake-up call. Many residents of St John left the island for St Croix, an island purchased by Denmark from France in 1733, located south of St Thomas and St John.

St Croix, like St Thomas and St John before it, relied heavily on slave labour. By 1792, the population of St Croix amounted to 22,000 slaves and only 3,000 non-slaves. In that same year, King Christian VII commissioned an investigation into the slave trade. Finding high mortality rates, low fertility rates, and a slave population incapable of reproducing itself, Christian declared the first official ban on the slave trade, to begin in 1803.

In 1847, King Christian VIII declared that all slaves would be freed in 1859. But in 1848 (the year of Revolutions in Europe), a large group of slaves gathered in Frederiksted, St Croix to demand their immediate freedom. The then governor-general of the island, Peter von Scholten, outnumbered and facing another potential rebellion, signed an emancipation proclamation on 3 July 1848.

Offloading its territories

Two years later, Denmark ceded its territory in western Africa to Britain. In 1915, a labour union was established to facilitate the employment of the freed slaves. And in 1917, Denmark sold the islands (St Thomas, St John and St Croix) to the US for $25 million. The US renamed them the Virgin Islands of the United States.

In very recent history, the question has been raised whether or not Denmark should apologise for its involvement in the slave trade, but the answer isn’t as simple as whether or not the country is sorry. For starters, an apology from a state often leads to some financial compensation, and it is believed Denmark may be waiting for a UN verdict regarding compensation due to the transatlantic slave trade – an issue that was raised in 2001 but has not yet been resolved.

Additionally, as the Virgin Islands are now a part of the US (99 years ago this Saturday!), a Danish apology may have a negative effect on diplomatic relations between the two countries. The US only apologised for the slave trade in 2009. Denmark’s apology may be seen as interference in US domestic affairs.

But according to Astrid Nonbo Andersen, a researcher on the politics of apology, it could still happen. “If the US one day offers Denmark the possibility of apologising and possibly paying some form of compensation,” she told Science Nordic. “Then it may happen.”