It read: “Kept 17-year-old as sex slave”. This was the headline of the tabloid Ekstra Bladet on 29 September 2005. Behind the headline was a large photo of an elderly man with curly grey hair and glasses with a caption saying: “I take the cook’s daughter whenever I want. It’s my right.”

A man of many talents

The man in the photo was the multi-artist Jørgen Leth. Born in Aarhus on 14 June 1937, Leth started his career as a journalist and cultural critic for leading national newspapers in 1959 after studying literature and anthropology in Aarhus and Copenhagen. In the 1960s he was part of the avant-garde scene in Copenhagen, and he published a first collection of poems, ‘Gult lys’ (yellow light), in 1962. The following year he made his début as a film director with the short film ‘Stopforbud’ (‘Stop for Bud’).

Since then he has written and directed more than 40 feature films and documentaries, many of which have been distributed worldwide. His most important works are considered to be the 13-minute-long surrealistic short film ‘Det perfekte menneske’ (‘The Perfect Human’) from 1967 and two cycling documentaries: ‘Stjernerne og Vandbærerne’ (‘The Stars and the Water Carriers’) from 1973, and ‘En forårsdag i helvede’ (‘A Sunday in Hell’) from 1977. He has also been affiliated with the Danish Film Institute in high positions as well as having worked as a professor at the National Film School and lectured at Berkeley and Harvard, among other universities.

A poetic cycling commentator

In spite of his success as a filmmaker and author, Leth was mainly known in artistic circles – the general public had little awareness of his existence. During the 1990s, however, that changed; Leth became a household name as a poetic cycling commentator on TV2, working together with his journalist colleague Jørn Mader. The Tour de France was particularly popular in Denmark in those years – a fervor that reached a climax with Bjarne Riis’s win in 1996.

Leth’s nasal voice – singing the praises of the French countryside and telling tales of rising stars and fallen heroes with commentaries such as “he treats the bike like a mean old cow who deserves it!” – became the soundtrack of many Danes’ summer holiday. His cycling poetry slam became legendary, helped by descriptions like the one of German cyclist Jan Ullrich during an individual time trial: “The power station from Rostock, a big stout stomping German, a torpedo shooting through the airspace, a bomb of power, almost ploughing up the asphalt – the legs are moving as big pistons on the German machine.”

For many viewers, the commentary was almost as big an attraction as the race itself, and some of the commentary duo’s remarks have become famous – there are several websites dedicated to the funny and quirky quotes by Leth and Mader.

A dirty old man

At the time of the controversy surrounding the cook’s daughter in 2005, Leth had been doing Tour de France commentary for no less than 16 years. He had also had success with ‘De fem benspænd’ (‘The Five Obstructions’), an experimental documentary he made in 2003 in collaboration with his friend, the acclaimed director Lars von Trier. In other words, most Danes knew very well who he was and, if they did not, they were certainly about to.

Ekstra Bladet’s caption “I take the cook’s daughter whenever I want. It’s my right” was taken directly from Leth’s first autobiography ‘Det uperfekte menneske’ (‘The Imperfect Human’). The book was published on the same day as Ekstra Bladet published the now famous front page and included graphic descriptions of Leth’s sexual relations with the 17-year-old daughter of his cook in Jacmel southern Haiti, where he worked at the time as a diplomat.

As well as accusing Leth of keeping sex slaves on their front page, Ekstra Bladet also published an interview with him by the journalist Kenan Seeberg, which supported the image of Leth as a dirty old man. However, when Seeberg read his own article in the paper, he found it had been changed so much by the editor that he could not answer for it. He quit his job in protest at Ekstra Bladet’s hand-ling of the story.

In spite of this, the story spread like wildfire and Ekstra Bladet sold 11,000 more copies than usual that day, sparking a nationwide sexual morality debate, which turned into a national smear-campaign against Leth. He was scolded and condemned in leading newspapers, on TV and by members of the general public in the following days and weeks. In fact the public denunciation of Leth – especially by angry feminists and often by people who had not even read his book – spread to the extent that he had to resign from his post as the Danish consul in Haiti and was fired from his job as a cycling commentator on TV2. He also received death threats, was ridiculed through crude caricature drawings and even described as a paedophile by a doctor in Politiken newspaper.

A cult icon

After some time, the sentiment began to turn in Leth’s favour. It turned out that many of his fiercest critics had not even read his book, and that nobody had interviewed his supposed sex slave to hear her side of the story or considered that Leth’s book was not just a personal diary, but a staged work of art with critical comments about his own persona.

Some newspapers realised they had gone too far and later apologised for the lack of documentation behind some of their articles. Politiken’s editor-in-chief, Tøger Seidenfaden, apologised on behalf of his newspaper for describing Leth as a paedophile and stated that this was a “groundless accusation”. More and more journalists, as well as famous Danish artists and authors, came forward to defend Leth, ridiculing the sanctimonious feminists and the narrow-minded attitude that had prevailed throughout the debate.

In 2009, TV2 offered Leth his old job as cycling commentator back, which he accepted, and since the controversy he has published two additional autobiographies in which, among other things, he describes his experience of the media storm in 2005. And then in 2010, he released the documentary ‘Det erotiske menneske’ (‘The Erotic Man’) which, with the aid of a lot of scantily dressed young women from Third World countries filmed in moments of simulated post-coital bliss, touches the very subject he got into trouble over. Once again, it’s a highly ambiguous venture, but this time the cries of ‘Dirty old man’ in the media were muffled by the memory of how badly they had got it wrong five years earlier.

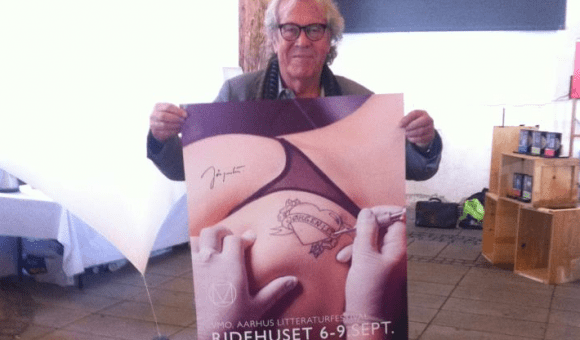

These days he is more famous and popular than ever. The younger generation in particular have taken to the now 75-year-old Leth, almost treating him like a rock star. Young women, some as young as 17, even ask him to autograph various parts of their bodies.

When Leth was asked why he thinks he is so popular with young people, he answered simply: “I think they like my honesty.” In any case, Leth has never been as sought-after as he is now. As the culture journalist Kim Skotte noted: “The smear campaign against Jørgen Leth was the best thing that could have happened to his career!”