Anyone who has seen a Hollywood film about a famous artist will be familiar with the clichés about artistic creativity.

Our man (for it is usually a man) is often portrayed as a troubled, romantic genius – sometimes emotionally unstable – usually also desperately poor. Despite all this, in a frequently drug or alcohol-fuelled creative frenzy he still manages to produce monumental works of art that amaze and delight.

Although there is a grain of truth in the Hollywood version, a new exhibition at SMK shows that craftsmanship, technique and sheer hard work play a vital part in the process. It is actually quite rare that masterpieces spring fully-formed from the brow of Zeus.

The exhibition collects more than 150 drawings, sketches and finished works from the 15th to 20th century to make its point. They are displayed in several distinct sections so that it is possible to trace the entire process – from the initial idea, through sketches, cartoons and reworkings – to the final work of art.

Radical modifications

It is surprising to see how an artist has modified his initial ideas quite radically, for example by repositioning figures or altering the perspective.

For example, in Alessandro Casolani’s picture ‘Woman contemplating a skull’, dated to around 1591, we have a two-sided sketch, of which one side shows the woman in full length on a chair and the skull on her lap.

On the other side, we see something more like the final picture, where the woman is seated at a table. Casolani even toyed with a third version where the woman is standing and the skull is on the table. Interestingly, this version was not totally discarded. Andrea Andreani used it as the basis for a woodcut in 1591.

The sketches for Diziani’s ‘Casting out devils from Monte Cassino’ show that the artist moved figures around, zoomed in on a particular area of the picture and even reversed the action in the picture before he was satisfied with the final result.

Honing their craft

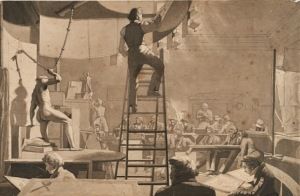

The exhibition also shows how artists traditionally honed their craft. There are a number of detail studies on display that can be anything from parts of the body to animals. They were often drawn from models or posed mannequin dolls.

Art education pre-18th century was largely carried out through training with experienced masters. Later, royal academies took over; it was necessary to ensure a supply of pictures to palaces and other royal residences, and the human form then became the most important aspect. In Copenhagen’s academy of fine arts, painting as a subject was not taught until the 19th century.

Softly, as in a morning sunrise

The part of the exhibition entitled ‘Creations’ takes four pictures from four different eras. The featured artists are all Danish: Abilgaard, Krøyer, Købke and Weie.

Christen Købke’s delightful ‘Morning view of Østerbro’ from 1836, which shows the end of Sortedam Lake where it meets what is now Østerbrogade, starts with some detailed figure sketches showing fishermen’s wives on their way into town from Skovshoved to sell their wares.

We know that Købke spent almost every morning in the summer of 1836 at the spot observing the sunrise and the people passing by. The artist then made three drawings, one of which even has extra paper struck onto it, which show the general street scene and the people. These are finally all fused into one large canvas. The painting was unusual for its time because it was rare for an artist to paint such a commonplace scene on such a large scale.

Getting it right

In the same section, the preliminary oil sketches for PS Krøyer’s ‘Portrait of Sophus Schandorph’ show how the figure of the poet and novelist was repositioned several times during the process to obtain the final result.

Schandorph, an extremely imposing figure, seems to be looking at something over the viewer’s right shoulder. Exuding joviality, cigar in hand and glass of wine on the table in front of him, I couldn’t help being struck by his resemblance to the English character actor James Robertson Justice!

Not just for art buffs

This exhibition may sound as if it is rather technical and ‘art nerdy’, but there is a great deal to enjoy. For a start there are works by some of the world’s most famous artists, albeit often sketches or graphic works, which are not shown that often. Rembrandt, Degas, El Greco, Carpaccio and Holbein, to name but a few, are all represented here.

But ultimately, what’s on show goes a long way to dispelling the ‘troubled genius’ myth and reminding us that art exists within an existing cultural framework as well as being of its time – and it is also very hard work.