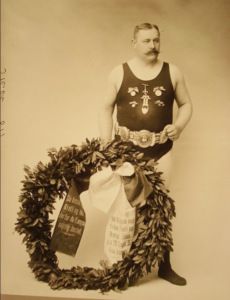

Brian Nielsen, Mikkel Kessler, the Bredahl brothers, no so much the Nielsen brothers – Denmark has had its fair share of high-profile boxers, but few can dispute that its first star of the ring, Magnus Bech-Olsen, was probably its finest ever fighter.

When the former stonemason triumphed in a title fight in Copenhagen in 1897, Denmark had its first and only, despite the aforementioned Nielsen’s best efforts, world heavyweight champion.

But the sport wasn’t boxing, it was wrestling.

Copenhagen clobberer

Born in Copenhagen in 1866, Bech-Olsen came to prominence in the 1890s when boxing was still in its infancy and playing second fiddle to wrestling. After all, ‘the’ Marquess of Queensberry (1844-1900) was a contemporary of Oscar Wilde who the playwright and author unsuccessfully sued for libel after he called him a Sodomite.

Bearing little similarity to the kind of sanitised wrestling we see today, the phrase ‘no holds barred’ meant exactly that in the sport during the latter half of the 19th century.

In order to win a fight a wrestler had to force both the shoulders of his opponent to the floor. Often little more than street fighting, unlicensed public wrestling had been outlawed in Copenhagen some years previously after one combatant seriously injured his opponent with an illegal head-butt.

Among the many colourful characters fighting during the 1890s was a Copenhagen baker, Søren ‘Iron Man’ Saft. The bulky Saft was a journeyman who travelled with his entourage through provincial towns and villages, challenging local tough guys to do battle. Despite offering a princely sum to anyone who could beat him, reputation has it that Saft never lost a fight.

However, it was Bech-Olsen who caught the imagination of the public.

Last orders for the Turk

The fight that made Bech-Olsen’s name was a high-profile match in 1896 against an unbeaten Turkish fighter, Memisch Effendi, who was the favoured champion of the Sultan of Constantinople.

The highly-publicised fight look place at the old St Thomas public auditorium on Frederiksberg Alle, and the hype surrounding the contest would rival that created by today’s boxing promoters. On the afternoon of the event the queue for tickets stretched well down Vesterbrogade towards the city centre.

At the time, a sports reporter wrote an article describing the event (see text box).

Wrestling in those days was lucrative, and with the proceeds of his wins Bech-Olsen, in true sportsman’s tradition, bought a pub, the since closed Cafe Bræddehytten on Helgolandsgade. His continued popularity ensured that customers flocked to be served beer by the vanquisher of the ‘Terrible Turk’.

Greeks bearing gifts

Although he could have happily retired for the rest of his days, Bech-Olsen’s greatest day was yet to come. On 26 August 1897, Bech-Olsen met the Greek world champion Antonio Pierri in front of a massive crowd at the Ordrup cycling track.

Although Pierri was a strong favourite to win the match, his Danish challenger upset the odds with a win that was, if anything, a little easier than his bout against Effendi.

In true wrestling tradition Bech-Olsen offered his defeated opponent a rematch, which took place the following weekend. Again the crowds flocked to the stadium, but the Greek wrestler fared little better. To the adulation of the crowd, the defeated champion handed over his coveted belt to the victor. Denmark had a new world champion.

New kind of ringmaster

More title defences and a tour to the USA followed, before Bech-Olsen eventually retired in 1903, but five years later he was back in the limelight, or spotlight if you like, as the owner of his own circus. For nearly a decade until 1919, he made Åboulevarden in Frederiksberg his home at a venue that could pack in 2,000 spectators a night.

The circus was still going strong when Bech-Olsen died in 1932, but two years was all his son Manne needed to run the operation into the ground.