Copenhagen is often ranked as being the world’s most liveable city. In 2018, a report released by ECA International revealed that the city provides its residents with excellent amenities: efficient transport systems, healthcare facilities and outstanding infrastructure.

Furthermore, Denmark is a regular on the United Nations Happiness Index published since 2012, which it has topped several times, never once falling out of the top five.

But 200 years ago, the Danish capital was nowhere near as happy, healthy and liveable as it is today. Indeed, Copenhagen’s recent history serves as an example of how a city can undergo drastic change and help the rest of the world tackle issues of air pollution and urban space.

Copenhagen’s journey becoming a model city inspiring other cities to be ‘Copenhagenised’ (yes, it’s an actual term) has been long and noteworthy. Let’s step back to understand how the Danish capital used to be and how far it has really come.

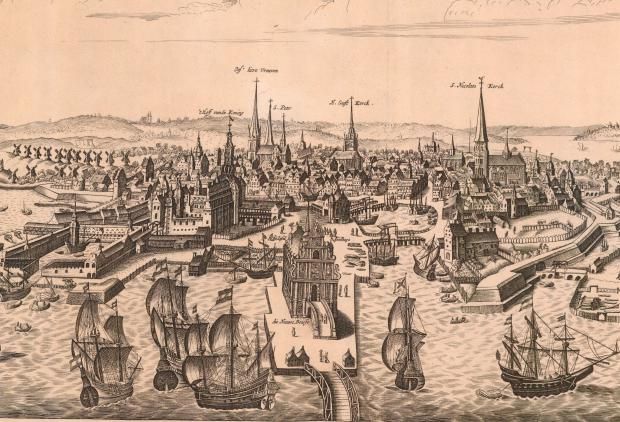

Old city limits

Like most European cities, Copenhagen in the early 19th century was fortified and the city centre was dotted with heaps of soil and earthworks to help defend the city from foreign invasions.

In those days Copenhagen had only four gates: Vesterport, Nørreport, Østerport and Amagerport. Everything that lay beyond these points was considered as being ‘out of town’, including the present-day Tivoli amusement park and the central railway station.

To get a better idea of how far the old Copenhagen extended, the location of the four gates needs to be visualised. Three of them stood in the areas where today’s train stations of the same names are located, while the fourth one, Amagerport, was to the south of the present-day city centre, where the district of Christianshavn crosses over onto the island of Amager.

King Christian IV of Denmark was a man of foresight. He knew Copenhagen would grow. In his reign, these painfully constricted city boundaries were significantly enlarged to include a large mass of land in the north of the city. For the next 200 years, this annex alleviated many of Copenhagen’s growing pains.

Population growth

By the end of the 19th century, the city had nearly 120,000 residents living in a very small area of land. People were forced to live in cramped quarters, with the ever-present threat of fire always looming. As part of the measures to keep the kingdom safe, the king allowed no buildings outside of the fortifications.

However, as the population grew exponentially the city allowed construction made of wood to make it easier to knock down at the first sign of threat.

There were also some less congested farm villages in the northwestern part of the city that appealed to those who desired a more stable lifestyle. Nicknamed ‘the Lakes’, the area consisted of a row of what are now three rectangular lakes – Sankt Jorgens Sø, Peblinge Sø and Sortedams Sø – which today are among Copenhagen’s top attractions.

Much of this area is split between the residential neighbourhoods of Frederiksberg, Nørrebro and Østerbro and sought after by city dwellers because of the tranquil ambience and tree-lined boulevards. It is difficult to imagine its past as the site of one of the city’s poorest neighbourhoods.

Cramped city

Space was becoming an intolerable problem in the overpopulated city of Copenhagen and the rigid line of fortifications left no scope for expansion in the territory.

In 1802, in a rather misguided attempt to tackle this growing problem, the mayor passed a law giving a tax break to landlords renting apartments less than 64 sqm in size. The idea was to give owners an incentive to divide the apartment so more families could be accommodated. This backfired when the landlords starting sanctioning extremely small apartments (28 sqm) to maximise profits. As a result, tenements originally designed for no more than 20 inhabitants now housed hundreds.

Living in a toilet

Residents of Copenhagen will be surprised to know that the fashionably located and spacious apartments they live in today were once four of five separate quarters in slum neighbourhoods.

Frederiksberg, Rosenørns Allé and Frederiksstaden were once home to the destitute and decrepit members of society who lived out their lives crammed into quarters with little sunlight, no plumbing and no facilities.

The plight of the city can be seen by the names given to its quarters – the Puddle, the Louse Club, the Crashing Hut, the Water Closet and the Poor Man’s Cavern – which connoted the conditions under which the poor residents lived.

In many buildings, residents had to climb rickety wooden ladders to reach their homes. But it was the basement dwellers who suffered the most. Their homes had ditches dug in the floors to contain the rain overflow, which amounted to at least six cm of water, street sewage and mud all through the spring and autumn. It’s no surprise that cholera, tetanus and diphtheria were rampant.

The city’s middle class – shopkeepers, merchants, civil servants and artisans – lived under different and relatively better conditions. They could own an entire apartment or house usually above their family business, and they even had servants’ quarters. However, these houses were also often cramped, allowing only a shaft of light to enter. The houses in and around the walking street Strøget are remnants of these.

Then there were the rich and aristocratic classes, who lived in large houses in and around Amalienborg Palace. These apartments were characterised by many rooms, fine interiors, spaciousness, dining areas, parlours and luxuries. You can see these aristocratic homes – which are often now offices and institutions – on the streets of Amaliegade and Bredgade as well as at the great yard at Saint Anne’s Square.

Economic downfall

Overpopulation wasn’t the only problem the city faced. The city gates were promptly locked at midnight until 7 am the next morning under the king’s supervision. However, an exception was made at Nørreport, where a fee of two skillinger (a considerable sum by today’s standards) could be paid to the night watchman in order to be able to enter.

For anyone whose daily affairs led them in and out of the city, the system was rather inconvenient. Every Wednesday and Saturday, hundreds of merchants along with their wagons lined up outside the gates of Copenhagen for admittance, sometimes even from 1 am to secure a place in the long queues.

rduous customs inspections, multiple fee charges and intricate receipts made the process cumbersome. In addition the gates were fairly narrow, making it difficult for large wagons to pass through.

Though originally designed to deter smuggling and robbery, by the 1850s the city lockdown had become an obstacle to its economic growth. Finally, in the late 1850s, the fortifications were demolished, taking away with them much of the city’s aesthetic appeal. To see what an original fort looked like, one must go to Kastellet – the remains of a 17th century citadel – and walk on top of the ancient earthworks.

Copenhagen today

The wealth gap that divided residents in the 18th and 19th centuries is now almost non-existent. Danish government’s welfare programs have helped narrow the income disparity among Denmark’s residents, which is now the second smallest among the world’s 34 most developed economies (according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

The idea of a generous government-provided cushion for ordinary people is deeply rooted in a nation with few outward signs of a pampered elite.

Copenhagen’s visual history has now been digitalised by the Copenhagen City Archives, with over 700 century-old maps and information available online. You can now delve deeper into and understand the medieval city’s development over the past several hundred years.