Today marks the centenary of the Schleswig Plebiscites – exactly 100 years since the second of the referenda – which resulted in what is now Southern Jutland re-amalgamating with Denmark.

Today, this united and apparently homogeneous nation-state is, historian Uffe Østergård explains, a far cry from the ethnically diverse and polyglot composite kingdom of Denmark’s past.

The centenary is a cause for celebration for many Danes, but it also prompts a reconsideration of Denmark’s identity.

Confusing history

Lord Palmerston famously said that only three people ever properly understood the Schleswig-Holstein question. One was Prince Albert, who was dead, the second a Danish statesman, who had lost his mind, and the third was himself, who had forgotten everything about it.

A Danish territory in the 13th and 14th centuries, Schleswig was then united with Holstein between 1386 and 1460. From 1474, that union broke and they were ruled as separate duchies of the Danish crown. Schleswig answered to the Danish monarchy, whereas Holstein remained under the Holy Roman Empire, with the king of Denmark acting as duke. This was the case until 1806, when the Holy Roman Empire collapsed and Holstein was incorporated into Denmark. This changed again in 1815, with the establishment of the German Confederation, when Holstein became a duchy once more.

A fate in focus

As time went on, nationalists on both sides claimed Schleswig. The German ones favoured the reunification of Holstein with Schleswig, whereas the Danish ones wanted Schleswig to amalgamate with Denmark.

In 1848, tensions boiled over and an independence revolt, led by the Prussian-backed German majority in Schleswig-Holstein, developed into the Three Years War (1848-51). A Danish victory resulted in Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg uniting with Denmark. Under the London Protocol (1852), Denmark agreed not to try making Schleswig any more aligned to itself than to Holstein.

A lost princess

In a bid to maintain Danish rule of the duchies, and worried about the future Frederik VII’s lack of children, Christian VIII changed the laws of succession to allow female heirs. This broke the German Salic laws of succession.

When Frederik VII died heirless in 1863, German-born Christian IX took the throne. Story has it, as first recounted by CPH POST editor Ben Hamilton in September 2014, that there was in fact an heiress: a girl born in 1851. The late Irene Ward, a woman from England, believed herself to be the granddaughter of that heiress, a baby girl who was smuggled out of Denmark in a joint Danish-British effort.

It was done out of fear that her illegal succession would cause a war in the duchies during a period when many sought to halt German expansion. Assisted by Queen Victoria, the girl was sent to Wales and raised in secret.

Lead-up to plebiscites

In 1864, Denmark’s Liberal Government tried to influence the Danish king into signing a constitution between Schleswig and Denmark. Doing so broke the London Protocol. A second war began between Denmark and the Prussian and Austrian Empire.

A defeated Denmark conceded Schleswig (including its large Danish population) and Holstein. The Austro-Prussian War of 1866 left both the former duchies in Prussia’s hands, and later, in 1871, they became part of the new German Empire.

The Schleswig-Holstein question did not die, however. The Austro-Prussian Peace of Prague in 1866 permitted a plebiscite to be carried out in the following six years to give the people of Northern Schleswig the power to decide their own fate. It was not until the 1919 Versailles Peace Conference that this clause was enacted.

The people decide

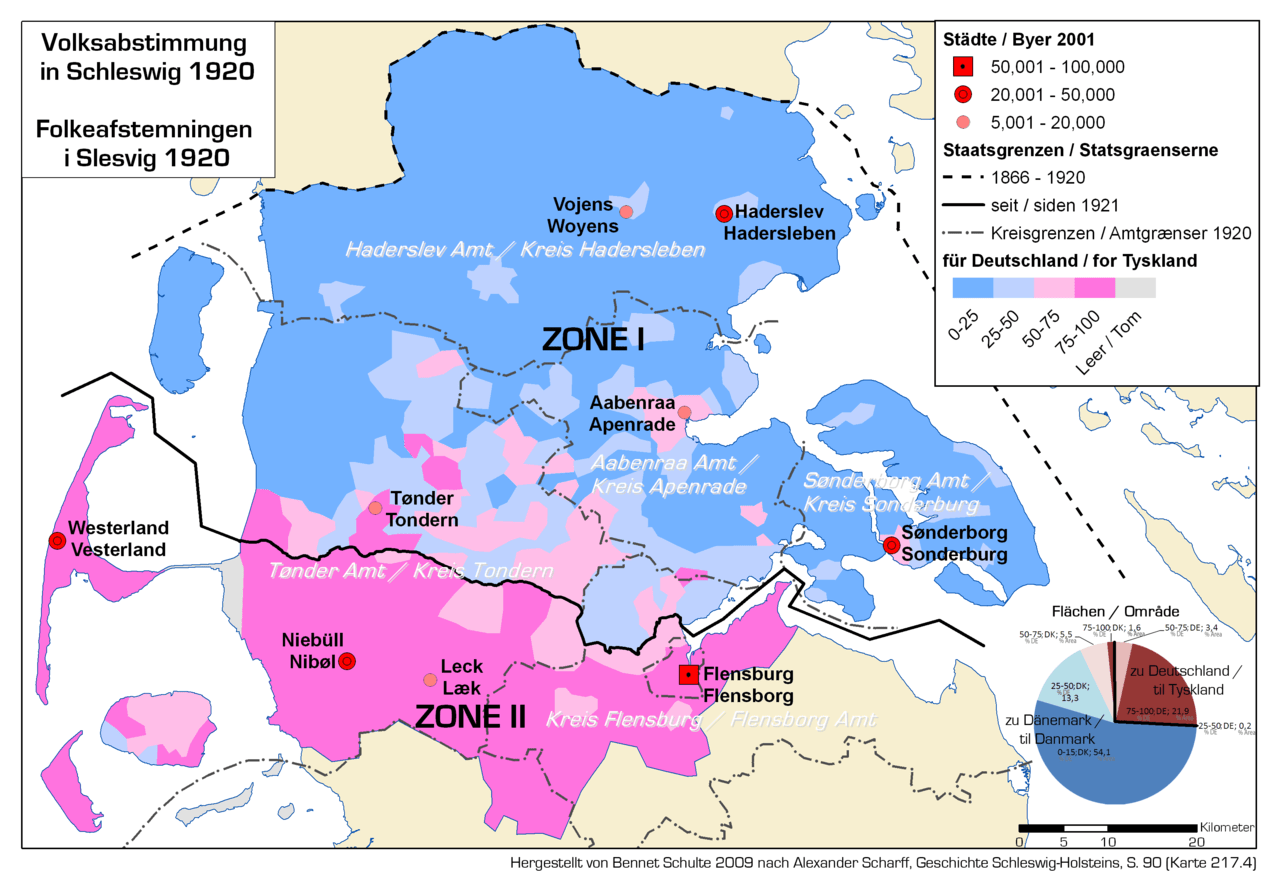

To decide Schleswig’s future, it was split into three voting zones based on demarcations designed to match the inhabitants’ own sense of their nationality (see map).

Zone 1 represented Northern Schleswig from the River Kongeå to the towns of Kruså and Padborg. Zone 2 encapsulated Central Schleswig from Flensburg in the North to the River Eider in the South. Zone 3 covered Southern Schleswig, but was excluded from the vote by the Danish government due to its strongly pro-German support.

Zone 1 voted with a Danish majority of 74.9 percent. Zone 2 voted with a German majority of 80.2 percent.

Celebrations ongoing

Reunification was completed on 9 July 1920 – a day that continues to be celebrated.

On 10 July 1920, King Christian symbolically rode across the new border on a totally white horse. On July 11, around 100,000 people, including the Royal Family and members of Parliament, assembled to sing nationalistic songs in celebration.

Every year, on June 15, all government buildings fly the Danish flag in honour of the reunification. In recognition of the centenary, celebrations began this year on January 10 and will continue until July 12. The Sekretariatet for Genforeningen wishes to “heighten the public’s awareness of the reunion’s epoch-making political and cultural significance to Danish society”.

Many left behind

However, the re-amalgamation is not positively considered by all. Some consider it a ‘loss’, and minority groups were left behind on both sides of the border.

In Northern Schleswig (Southern Jutland), there still live an estimated 15,000-20,000 Germans. Concentrated in the German districts of Nordfriesland, Schleswig-Flensburg and Northern Rendsburg-Eckernförde, meanwhile, are an estimated 50,000 people in the Danish minority.

Although relations appear amicable today between minority and majority groups, the situation is not perfect. The Council of Europe’s News Room, in January of this year, wrote that Denmark needs to do more to “address rising intolerance” against the German minority. They suggested additional steps to “promote intercultural understanding”, such as implementing bilingual signs for South Jutland municipalities.

Still relevant

The Danish and German minorities are not alone. Groups exist around Europe trapped within political boundaries they haven’t chosen. Many Scots, for example, hope for a vote to choose independence from the UK but within the EU.

Closer to home, independence sentiments exist in Greenland and the Faroe Islands, with foreign interests complicating the picture.

Contesting identities and affiliations are a constant in human history. Bearing past conflicts in mind will hopefully avoid more bloodshed and marginalised people in the future.