The National Gallery of Denmark yesterday opened a major exhibition of the work of CW Eckersberg entitled ‘A Beautiful Lie’. Eckersberg, who lived from 1783-1853, laid the foundation for the creative period known as the Golden Age of Danish painting.

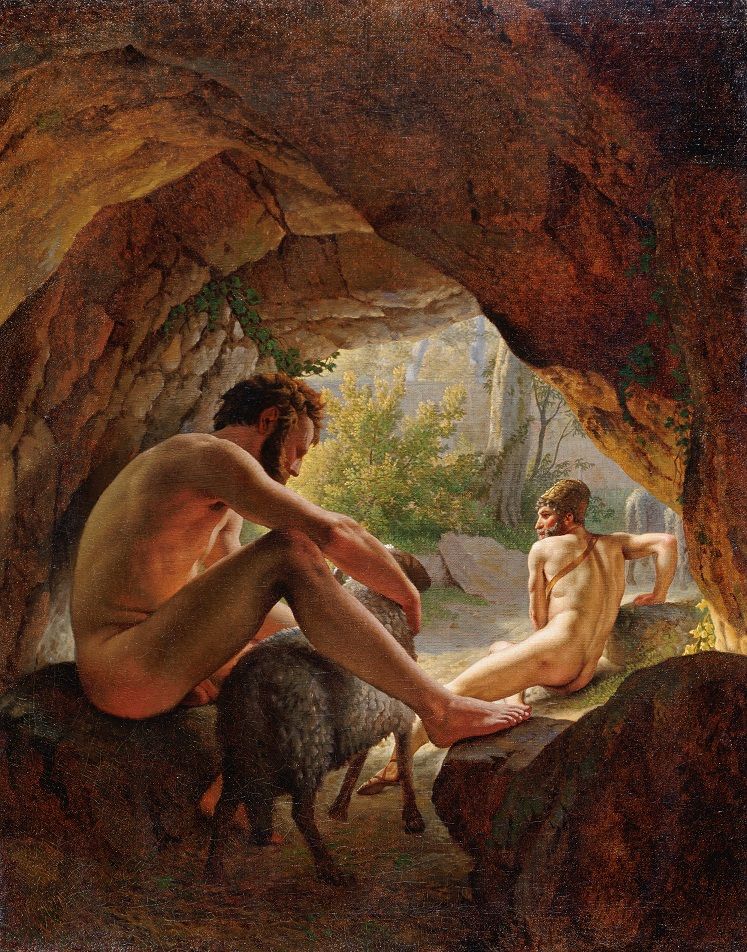

Eschewing the strictly chronological approach, the exhibition is divided up into five sections: views of nature, face to face, image construction, the human body and storytelling.

What you get is not what you see

Although at first glance, Eckersberg’s work appears to be a very accurate picture of the world around him, the title of the exhibition, ‘A Beautiful Lie’, suggests that Eckersberg was a master of manipulation. He carefully pared away details that spoiled what he saw as the aesthetic perfection of his subjects.

A good example of this is his famous view of Rome through three of the arches of the Coliseum (see above). When this is compared with reality, it is clear he would have been unable to see the views through the individual arches at the same time. Eckersberg presents us with an idealised snapshot of the world, where beauty and harmony take precedence over accuracy.

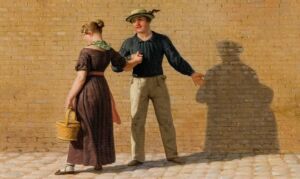

Another example is the delightful picture of a sailor taking leave of his girlfriend (see above). At first glance a straightforward scene, but look closely and you can see the shadows cast on the wall intertwined as if in an embrace.

Tightly framed

His Roman landscapes bear witness to just how carefully controlled everything is. The framing of the picture is all-important and the world has been neatly arranged to form a harmonious whole.

Eckersberg was also a master portraitist. His picture of his mentor, the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, is so life-like you can almost reach out and touch the material of the sitter’s gown.

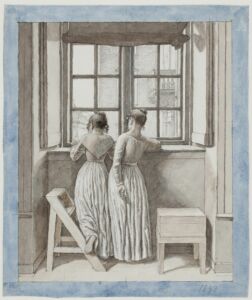

The double portrait of Bella and Hanna Nathanson (see above) shows one girl standing face on and the other in profile, contemplating a parrot in a cage. The green of the parrot and its red neck feathers are mirrored in the green of the girl’s gown and her ruby earrings.

As the many fine maritime subjects on display testify, Eckersberg was very interested in ships and the sea. For most of his life, he meticulously kept a diary recording details of the weather, clouds etc.

A great find

On display for the first time is a small oil cloudscape study, recently identified by a sharp-eyed curator as being by Eckersberg. It had been partially overpainted and hung in the toilet of a hippy’s flat in Østerbro. After restoration, the study was valued at around 1.9 million kroner.

This is presented beside a picture of the Russian ship of the line Azow, in which the almost identical cloudscape provided a crucial clue to attribute the study.

This excellent exhibition shows just why Eckersberg is considered one of the key figures in Danish art.