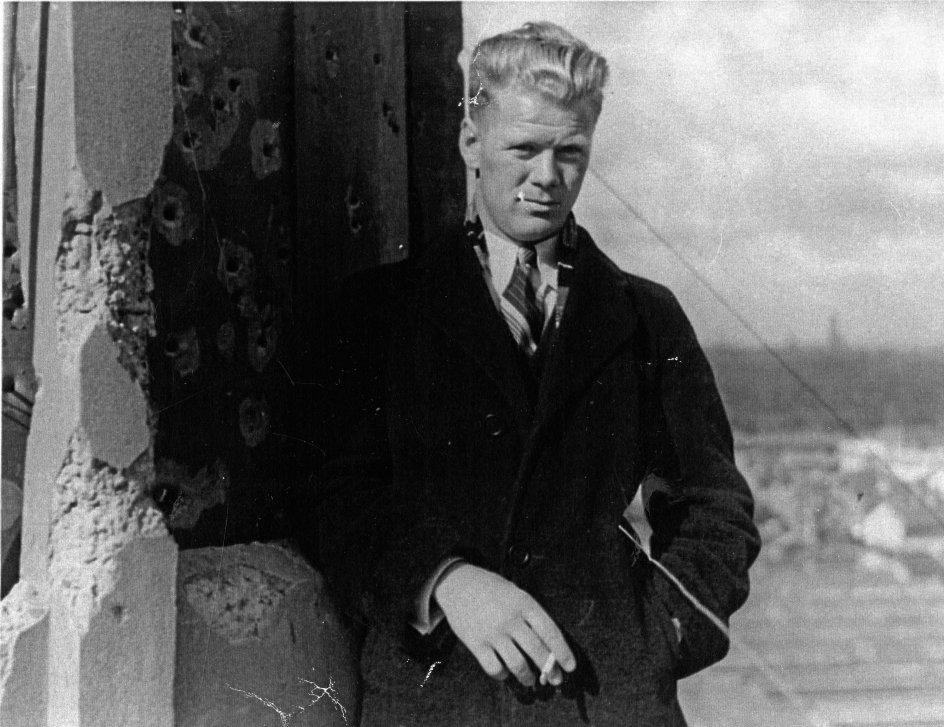

Finn Juhl, who would have turned 103 this year had he not died in 1989, is one of Denmark’s most celebrated designers, best known for introducing Danish Modern to the US and his work at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

He was educated as an architect, but his real passion was furniture design, an area in which he was self-taught – a fact that he never failed to remind everyone about. He is best known for producing soft-edged furniture with a focus on form over function that broke with the traditions of the time.

His entry into the world in 1912 was a difficult one, and his mother died shortly afterwards.

He was brought up together with an older brother by his authoritarian father, who was a textile wholesaler. As a child Juhl wanted to become an art historian, but his father disapproved and convinced him to become an architect instead. He duly studied architecture from 1930 to 1934 at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, where noted architect Kay Fisker was one of his lecturers.

Blazing new trails

Juhl was a hard-working student – an enthusiasm that granted him the opportunity to work for Vilhelm Lauritzen after university. Nevertheless, he still found time to focus on his true love – furniture education – and following his graduation it wasn’t long before his hobby became his line of business.

From his design practice in Nyhavn, which he opened in 1945, he specialised in interior and furniture designs, working with, among others, cabinet maker Niels Vodder. He quickly became known for making unusual, expressive and sculptural pieces, which were influenced by modern, abstract art.

The works broke with tradition, putting more emphasis on form than function, and initially they were met with much criticism. “Aesthetics in the worst possible sense of the word,” commented one detractor in 1939 about his Pelican Chair. Nevertheless, the reaction was mostly positive, and his soft edges and organic shapes became popular.

American connection

Still, it wasn’t until a chance meeting with the American architect Edgar Kaufmann Jr that Juhl’s career began to take off internationally. It was Kaufmann – the leader of the Department for Industrial Design at Merchandise Mart in New York, who would go on to become one of the Dane’s life-long collaborators – who got Juhl involved in the design of the new headquarters of the United Nations in New York, which opened in 1952.

Juhl was commissioned to oversee the interior design of the Trusteeship Council Chamber – an accomplishment that sealed his name in design immortality. While his career went on to dip somewhat in the 1960s and 70s, interest in his work soared in the 1980s and today his designs are sold by Onecollection, the duo Ivan Hansen and Henrik Sørensen who obtained permission from Juhl’s second wife, Hanne Wilhelm Hansen, to carry on producing his work.

“The special thing about Finn Juhl’s furniture is that they smile at you,” enthused Hansen in a recent article in Weekendavisen, explaining his love of the designer’s work. “If you for instance place a group of colourful Pelicans in a modern office, something happens. They bring art, colour and happiness into the room.”

The legend continues

It is sometimes overlooked how versatile Juhl was. He designed refrigerators for General Electric, as well as numerous glassware and ceramic pieces and, lest we forget, he was a trained architect. During the Second World War he started building his own house and family home, a building that today is part of the Ordrupgaard Art Museum. Juhl felt it was important to interact the rooms in the house with the outside surroundings.

The house was the home of his second wife until her death in 2003, after which it became a national heritage site and part of the art museum. Since then the Wilhelm Hansen Foundation has every year awarded the Finn Juhl Prize to a furniture designer or manufacturer with a special reference to chairs. The recipient receives 175,000 kroner and the award ceremony takes place at the museum.

“One cannot create happiness with beautiful objects, but one can spoil quite a lot of happiness with bad ones,” Juhl remarked in 1951.