Walking through the Copenhagen museum dedicated to Bertel Thorvaldsen’s sculptures, one is struck by the lyrical finesse and grace that the artist coaxed out of a simple slab of marble. As art historian Keld Zeruneith put it, “the stones seem to emit light.”

Born in 1770, Thorvaldsen lived to see one of Denmark’s most politically disastrous periods, the Napoleonic War years, give way to one of its most artistically triumphant, known today as the Golden Age.

In the early 19th century, the nation suffered humiliation after humiliation: first the entire naval fleet was captured in a surprise attack by the British in 1807, and then Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden in 1814, and financial collapse followed.

Having suffered the loss of international political prestige, the county began to focus inward, turning to the arts as a fresh source of national pride.

For the glory … in Rome

The move was on to find artists who could become the new national heroes. Thorvaldsen fitted the bill; hailed early on as a child prodigy, he had gone on to establish a reputation as an exceptional talent and a commanding character.

“With his imposing appearance and charismatic personality, Thorvaldsen was the very image of artistic genius,” remarked Zeruneith.

The fact that Thorvaldsen had left for Rome in 1797 did not keep him from being considered a Danish national icon.

Couldn’t walk the line

A sojourn to the south was regarded as essential for all artists of the day – only most of them returned home soon after. Thorvaldsen did not. For over four decades the sculptor stayed in Italy, where he could be found nightly in the local bodegas dancing, gambling and womanising.

Of all of these vices, the last is best recorded, and Thorvaldsen had a particular taste for married woman. One of these women was the wife of the artist’s most generous patron, the famous Danish archaeologist Georg Zoëga.

But the infidelities did not stop there. During Thorvaldsen’s affair with Zoëga’s wife, the young sculptor also became entangled with the lady’s maidservant, Anna Maria Magnani, who was also married.

Not so Magnani-mous

The affair would last for more than 30 years. In time, Magnani would leave her husband and children to start a new family with Thorvaldsen.

The relationship, however, was not a tranquil one. Thorvaldsen would simply disappear at times, leaving Magnani to take care of their children on her own. When Thorvaldsen finally returned to Denmark in 1840, Anna was not with him. He confessed once to a friend: “How could I marry – what woman would not make a cuckold of me?”

As an artist, Thorvaldsen was enormously dedicated. Beside his bed he had a modelling wheel with clay in case an idea came to him suddenly in the night, and during the 40 years he spent in Rome, he had no less than four workshops running simultaneously.

Sculpting it big

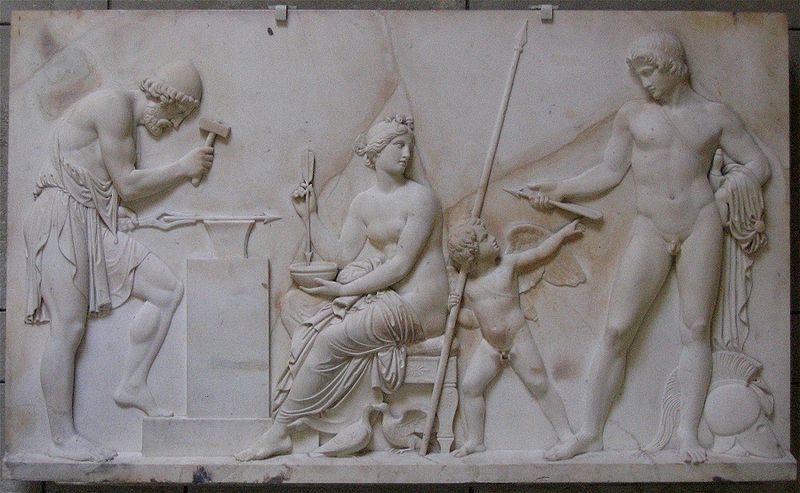

Perhaps his first great breakthrough was his sculpture of Jason with the Golden Fleece. A life-sized statue of the Greek mythical hero, this piece earned Thorvaldsen praise all over Rome. The Italian sculptor Canova praised the work’s “magnificent new style”.

Back in Copenhagen, Thorvaldsen’s work was much sought after, and in 1820 he received a commission to create a statue of Christ and the 12 apostles for the alcoves in the Church of Our Lady.

He accepted the commission and carved the pieces, shipping them back to Denmark. When the statues arrived, however, it was discovered they were too large. To this complaint the artist responded: “I didn’t make the pieces to stand in sentry boxes.”

Buried in museum

Heading into the final stages of his career, the ageing Thorvaldsen revealed that he had long considered making a museum for himself, suggesting publicly that he planned to buy a villa somewhere in Rome and convert it into a showplace.

Fearing this would deprive Denmark of works by its most famous artist, the government authorised the building of the Bertel Thorvaldsen Museum right beside Christiansborg Palace.

The museum was completed in 1848, the year of Thorvaldsen’s death, and the artist was buried in the museum’s central courtyard, where he still rests today, surrounded by his works.