We live in a rapidly evolving, hyper-connected world, where goods, capital, and people are more mobile than ever before. But, whereas countries have shown a willingness to co-operate on exchanging goods and capital, the international community has shown little appetite for improving how it governs human mobility.

Initially global solidarity

After the wide-scale persecution and displacement of people in World War II, world leaders took the bold step of crafting the 1951 Refugee Convention. In doing so, they relinquished a measure of national sovereignty – by accepting the principle of non-refoulement – in order to promote global solidarity towards refugees.

On the other hand, country leaders saw migration as something temporary that could be managed ad hoc through unilateral or bilateral agreements primarily designed to fill specific labour-market needs in developed economies. In hindsight, it is now clear that this approach was inadequate for dealing with the upsurge in human mobility that came with global and regional economic integration.

Migrants aren’t goods

When writing about guest workers in Switzerland, Swiss playwright Max Frisch once observed: “We asked for workers. We got people instead.” He meant that migrants are not goods that can be exported or imported, and they should not be exploited as if they were. Migrants are human beings with rights, and they are motivated by a complex combination of personal desires, fears, and familial obligations. Many migrants are searching for jobs because they have missed out on globalisation’s unequally distributed gains, and they see no future for themselves if they remain where they are; countless others have been displaced by conflicts or natural disasters.

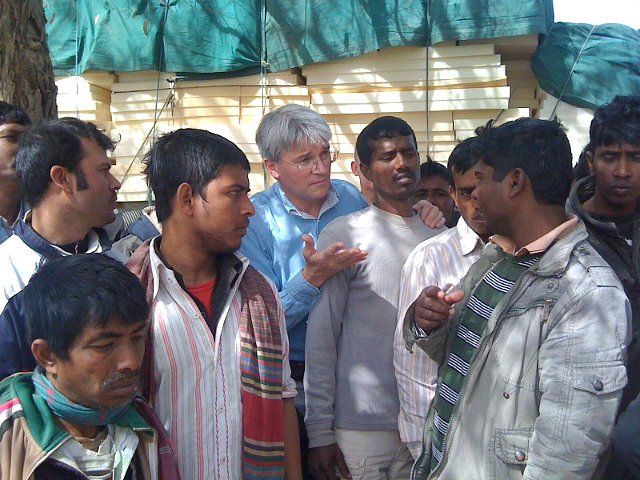

Today, ungoverned migration is threatening geopolitical stability, burdening border controls, and creating chaos around the world. The current mechanisms for managing migration have clearly failed to meet existing needs. The world needs a new, comprehensive global-governance framework to address all issues relating to human mobility. Achieving such an outcome was Bangladesh’s primary objective as chair of the 2016 Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD), which culminated with the Ninth Annual Forum Meeting in Dhaka on December 10-12. In attendance representing Denmark was Morten Jespersen, the under-secretary for global development and co-operation.

Positive contribution ignored

In 2015, as part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, world leaders pledged to co-operate on migration issues and to “facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration”. The SDGs acknowledge migrants’ positive contribution to inclusive growth and sustainable development, and it is high time that our leaders follow through on their promises.

Sadly, governments worldwide have become preoccupied with deterring migration and restricting people’s movement, rather than creating safe, dignified channels for human mobility. Unsurprisingly, this obsession with control has had little impact on irregular migration flows, because it runs counter to the pull of market forces and the push of personal aspirations.

Hope despite the populists

Populist politicians have taken advantage of the current situation by politicising migration and scapegoating migrants for socioeconomic problems such as unemployment, welfare-system strains, and deteriorating social cohesion. But there is still room for hope. When world leaders gathered at the UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants on September 19, they reaffirmed migrants’ human rights and committed to strengthening global governance on this issue. At the centre of the summit’s unanimously adopted New York Declaration is a commitment to develop two global compacts: to share responsibility for taking in refugees, and to ensure orderly, safe, regular, and responsible migration.

The government of Bangladesh proposed the second compact in April 2016. That compact, which will be adopted at an inter-governmental conference in 2018, offers an historic opportunity to improve the way governments and other stakeholders co-operate on migration. Building walls and discriminating against migrants or refugees on the basis of ethnicity or religion is antithetical to the 2030 SDG agenda, which aims to free people from the shackles of poverty, reduce inequality, and promote shared prosperity.

International community must act

The international community must now ensure that the new global compacts promote these broad ambitions. This will require national governments and global-governance institutions to implement bold policies that make migration both easier and more orderly. It will also require them to protect migrants and refugees’ rights, prevent ethnic or religious discrimination, and provide emergency assistance when needed. And it will encourage them to maximise migrants’ positive economic impact on both their new countries and their countries of origin, by reducing financial and human costs and integrating newcomers into the labour market.

To achieve the best outcome, the two global compacts will need to be pursued in a co-ordinated fashion and treated as two parts of a single framework for governing migration. In 2017, governments will begin to negotiate the details of this future framework. This may include a legally binding convention; a political declaration of principles to guide conduct; or operational commitments with goals, targets, and indicators of success, combined with a robust monitoring mechanism.

The potential is huge

These options should not be seen as mutually exclusive. If diplomacy prevails, and international arrangements are crafted carefully, one could imagine an outcome similar to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement: binding commitments in some areas, non-binding guiding principles in others, and a shared promise by member states to take concrete action and to report their progress regularly. Such an approach would help to guarantee effectiveness.

As the chair of the GFMD, Bangladesh will communicate the Dhaka summit’s recommendations to countries’ negotiators. We will push for an agreement among political leaders at the inter-governmental conference in 2018 that vastly improves how migration is managed. With international co-operation, we can unleash the full social and economic potential of migration. And, in doing so, we will make migrants safer, societies more harmonious, and economies more prosperous.