He put his right hand behind my head and pulled it to the right. Meanwhile, his left hand lifted my right arm in the same direction. I was on the ground in a few seconds and Coogan almost fell after me as he finished the move. He pulled me up with two hands and it was my turn to try. “It works and guys are afraid of you — they think you know more, even though you don’t. I used it twice in action and the guys were immediately going: ‘Nej, nej, undskyld, det var ikke det jeg mente.’”

Walls and shelves full of history

We started talking karate soon after he showed me a green engraved plate given to him as a gesture of appreciation by his fellow members at Copenhagen Celtic – the football club he co-founded – and a picture of his shocked expression in the moment the door opened onto his surprise 60th birthday party about six years ago. “But this is the most impressive one,” he said, pointing at a large framed piece of paper with a picture and some writing on it, including some Japanese letters. “My son’s black belt diploma,” he said proudly with an Irish accent. “I was standing in the kitchen one day, cooking, and I felt this slap on my head,” Coogan told me and slapped me lightly. “I said: ‘Fuckin’ eh, what’s going on!?’ I thought Sean was slapping me to get me pissed off. I turned around and it’s Sean, but he’s not slapping me, he’s kicking me with his right foot. He said: ‘Dad, I need to practise my kicks.’ Imagine how hard it is kicking the top of someone’s head while standing.’”

Coogan assisted Sean in teaching some kickboxing for a while and that’s where he learned the move I was taught. Besides being a skilled martial artist, Coogan’s son is now also a journalist at DR and a player for CPH Celtic. “Sean is Irish,” Coogan said. “He has Celtic scores in his head,” he added, referring to Glasgow Celtic, Ireland’s most beloved team outside the country and the namesake of his own club. “As for my daughter Megan, she’s more Danish. She thinks people in Cork are a bit …” said Coogan, gesturing circles at his right temple jokingly.

In the corridors of Cork

Yes, Aidan Coogan comes from the second largest city in Ireland: Cork. Growing up there, he went to a school for learning trades (“I have never experienced so much violence in my life”), when one day an unexpected new opportunity presented itself. “I’ll tell you a very quick story now, and I hope I’m not boring the pants off you. The teacher came in and said: ‘Does anyone want to become a chef or a waiter?’ For fuck’s sake, I thought, that was a surprise. ‘There’s an interview in the afternoon and you get the afternoon off if you go for it’. So we went and there were guys from other schools there and we were kicking the shit out of each other in the corridors when the interviewer came out and said: ‘If there are any more fights, all the interviews are off!’ Then, it was my time to go in and the interviewer said: ‘Why do you wanna become a chef?’ I started telling him: ‘I work in Blackrock Castle’ – it was the place in Ireland.

Then, the guy asked: ‘You work in Blackrock Castle?’

‘Yes, but only as a bar boy.’

‘Do you know Jim Gallagher?’

‘Yeah.’

‘He … I taught him!’

All of a sudden, there was no more talk about me, it was ‘How’s Jim doing and all that, and ‘Oh, by the way, you got the job, you’re through.’ So what you know is who you know. My mother was so proud.”

Chop that flour son!

Coogan packed up and moved to Maynooth to attend the two-year catering college course. He was 15 at the time: “That’s where I became a man. When you go in for the first time, you have never put on a chef’s uniform before. You haven’t a fucking clue. And you know what the guys in their second year had us doing? Chopping flour. For six hours, til we got blisters. That’s cruel. They were takin’ the piss. That was just tradition, but when we became second year students we stopped it; we said that’s not fair to anyone. There was no more shit.”

Today, the place is a college in Ireland but it used to be a seminary. “We were catering for the guys who were studying to become priests. It was actually child labour. We weren’t getting any money and we were working fuckin’ six days a week. Catholics, huh? Fuck off.”

A tale of many cities

After he graduated, Coogan’s job and desire to travel took him many places. First there was Killarney in Ireland (“It was a shithole”), then Kinsale (“I fell in love with the place”), Hotel St Gotthard in Zürich (“They spoke French, German and Italian and no-one spoke a fuckin’ word of English. Bastards. And they treated me like shit. But they taught me how to cook … really”), Swansea in South Wales (“It was an experience that changed my life. I’d been a virgin up until then, because I was waiting for this girl I was in love with, and, well, the Welsh women have no morals, so I died and went to heaven. And I mean that. Also because the price of a pint was 39 pence at the time in Ireland, and in Swansea it was 15. I got over my heartbreak eventually as you can imagine. But after almost three years, I realised that if I didn’t leave now I was gonna die soon. Between drinking and screwing around there wasn’t much else and that’s not good. You need to focus in life”), Frankfurt (“I knew I needed a kick up the arse and I got a kick up the arse because Germans won’t take any shit”), Munich (“the most beautiful place I’ve ever been to. By then I spoke German”), Perth, Australia (“Put your clock forward eight hours and travel back in time ten years – it was so old-fashioned, and I thought Ireland was bad, but Perth is the arsehole of fuckin’ nowhere”). And Denmark.

Got some shampoo?

The restaurant Coogan worked at in Copenhagen is called Peder Oxe. “The women were … I swear to god, you had to be a model to get a job there. And in Denmark in general, girls would come down with no clothes and say: ‘Coogan, can I borrow some shampoo?’ Just unbelievable, you know. But it was natural – it wasn’t teasing or anything. It was very difficult for an Irish guy to see girls so natural. And sex was just, no problem, you know. No-one got jealous if you had sex with someone else – it was just free and easy.”

However, it was actually an Australian girl Coogan fell in love with while in Perth. Her name was Tracey: “A good girl.” Their road was long and winding: Coogan moved to Denmark, Tracey got married, they reconnected, she divorced, and finally she decided to follow Coogan to Copenhagen. “She phoned me and she said: ‘I’m giving up my job, I’m getting divorced, I’m coming to live with ya.’ Can you imagine that? I mean, I was in shock. For a girl to take such a risk on me …” Coogan’s eyes started to well a bit. “That’s why, though we’re divorced now, we’re best friends. She gave me two great kids and she gave up a lot for me. A lot. She gave up her teaching job and came over here to do dishwashing. Can you believe it? Until she got a job at an international school later on.”

Coogan’s Copenhagen Celtic

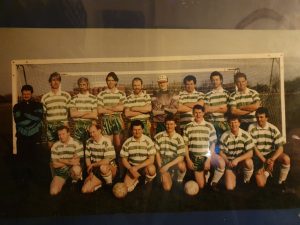

Then, in 1981, Coogan and two colleagues started the football club that would eventually become Copenhagen Celtic. “That was the best thing we ever did. I was sous-chef in Peder Oxe, and so I was hiring staff. And a very important question was whether you could play football. If you could cook and play football – but playing football was a little bit more important in those days. We won the league the first year. Mostly Irish, English and Scottish players and two Danes. If it wasn’t for the football team, a lot of guys would’ve gone home. A lot of them stayed for the football and then eventually they met some Danish girls and settled. Now we have nine teams. One of the guys we can thank for that is Baller, who I just need to mention because he has done a lot for the club. The club has got huge. This is also very sad in a way. In the old days, we knew every player. Now there are so many teams and it’s mostly Danes. I can’t keep up with it.”

There are CPH Celtic pictures all over the walls at Coogan’s and, walking around in Kennedy’s Irish Bar the next day, I came upon another one, right across the end of the long bar with its 20 taps. Tim Tynan, the co-founder of Kennedy’s, used to play for the team himself.

Tim and the kibbutz

Like Coogan, Tim is a true adventurer, an Irishman who travelled and saw the world before eventually settling in Denmark. “You can tell everyone I was a refugee of the heart. The classic story.” Tim met ‘the girl’ at a kibbutz in Israel in 1988. “Many people had the same experience: met some young Danish girl in a kibbutz. The amount of Danes that used to be out there was unbelievable actually. There was also a history of zionism after the Second World War in Denmark. The story goes that Danes helped many Jewish people get across to Sweden on boats and stuff. The thing that you went there – became a volunteer, helped out and met others from all over the world – was a thing people did back then. And I just ended up there … After a drunken night with somebody I met in Crete. We decided we would go to Israel via Turkey – where we spent six weeks first.”

Prior to that, Tim worked in a taverna in Greece: “That was pretty cool; money was shit, but it was sunshine all year long”. Prior to that, he had a job in Germany, and prior to that, he travelled around Europe in a camper van with a friend. He left Ireland at the age of 21.

One large Irish family

All of the rest of Tim’s family stayed in Ireland, and what a family that is: he has six sisters and two brothers. Tim remembered going camping around Ireland in a Renault 4L: “With eight kids on the backseat and the baby on my mother’s knee in the front. And there were no seat belts. But my father drove what, 55 km/h? Eventually he bought a minibus … or, an old van he tried to turn into a minibus.”

Tim also remembered another side of growing up in County Wexford: sports: “Back then, if you went to a match as a kid, playing hurling or football, your parents never went to see you play when you were 10 or 12 years of age. You just went down to the neighbour, who was the trainer of the team, and he would take 10 kids in the back of his Hillman Hunter and we would drive off to the match. He’d drive us home again, sometimes stopping in the pub on the way or even having a couple of pints of beer. And he’d be smoking at the same time as driving us. We’d go into the pub as well and he would buy a large bottle of soda and we’d share that between us.”

“There wasn’t much money going around,” so Tim worked on occasion from the age of 12. He picked strawberries in the summer. “Whole families would pick them sometimes. Also, some people used to move out of their homes and live in a caravan for the summer so they could rent out their bedrooms to people from Dublin. Airbnb!”

Pray first, pleasure later

Religion was also a dominant element of many lives in Ireland in the 70s. When I inquired about the reach of Catholicism into the Tynan household, Tim simply smiled and then responded: “We used to say the rosary at night-time. Yeah, most days. And the fun bit was when you tried to go out Saturday night, and your mother tried to get you to say the rosary before you went out. And the most embarrassing thing was when a friend came to collect you, and they would also have to say the rosary before you went out. There was a lot of tongue and cheek about it, but there was a lot of religion in the house.”

Back to the kibbutz girl

But back to the Danish girl Tim fell head over heels for: after the kibbutz, she went with Tim to London, where he worked in construction. She then moved back to Denmark a year and a half later and it was Tim’s turn to go after her. Thus he arrived in 1990.

However, their relationship eventually “fizzled out”, as Tim put it. “Heart got broken, boy was shattered … but boy regained his confidence. I left Denmark and travelled some more, did a round-the-world trip and came back again and settled down. And I do like it here. It’s a funny thing about Denmark, and a lot of people realise this when they’ve been here for a while: you get used to the system, the way of life here. You feel safe and comfortable. And then, of course, I met another woman, who I married and have children with, so you can say I got stuck here, but I’m happy to be stuck here.”

“This second woman: was she also Danish?” I asked. “Yes … might not be the second one though; there might have been a couple in between. But we definitely don’t want to talk about them.”

Ode to Irish coffee

Now, let’s stop for a moment here for a word on Irish coffee. Around the middle of our conversation, after he told me how good he is at making them, I asked Coogan if I might have a try. He didn’t have all the ingredients, but he offered me some hot toddy instead: whiskey with hot water poured over it. Then in Kennedy’s it finally happened. “We have the best Irish coffee in town. You can put that in writing,” asserted its server with a finger pointing in the air in front of him for emphasis, either before or after I ordered one for myself. Let’s just say, I had three of them and that Tim wouldn’t let me pay for a single one. It’s the only one I’ve tried, but I don’t have much doubt that Tony is indeed telling the truth. By the way, Coogan also revealed to me the origins of Irish coffee, as well as duty free shops (both happened the same day and in Ireland), but that’s for another time, a different place and a longer word count.

Being Irish in Denmark

“The ladies love the Irish accent,” the Irish coffee provider now identified as Tony Kennedy told me from behind the bar while I was interviewing his partner in crime at a corner table. The two are the masterminds behind Kennedy’s.

Tony also told me about his first girlfriend in Denmark: a Hungarian woman. The relationship didn’t work out though: “Us Irish boys are a little wild. It’s hard to pin us down.”

“The first relationship never works out here,” Tim added, so I inquired: “Why is that?”

“I can’t answer ya!” he replied before answering: “What it is, is … when we get here, we go, wow so this is what freedom is like!” ‘I love Rock ’n’ Roll’ was playing in the background at this point. “Whether it’s freedom of the women or just the way of life.”

“Things were very laid-back here. You could do what you wanted and nobody really worried about you. They mightn’t interact with you sometimes, but they still didn’t mind that you did something different than them. I think that attitude has changed. Now a lot of people want you to conform to what they are. But there is still an element of Danes being relatively non-judgemental.”

“We totally embraced the nightlife here, us Irish lads. We partied all night,” added Tony, who also explained to me that he made his hobby his living when they opened the pub.

“I used to love going home 7 o’clock in the morning, watching people go to work,” added Tim.

Tony laughed: “Walking the dogs. But yes, everything was more liberal here than in Ireland.”

“Yeah, and you were never judged. Other than … by your girlfriend of course.”

Hvad siger du?

But being a foreigner also provided some trials and tribulations. Once the guys were here and decided to stay in Copenhagen, they had to deal with the strange creature who inhabited their new home: the Dane.

“Here’s another story for ya. It’s a classic actually,” Coogan said with a smile on his face. “The first Danish school I went to, they told me that my pronunciation was very bad and I should go and learn to read and write. So I went and learned to read and write Danish in a different school. One day, the teacher called me aside and told me that I was doing really, really well. First compliment I ever got about my Danish. So, I go down to get the train home to Lyngby and there was a kiosk at Nørreport Station. It was covered in signs of Mars bars all over the place. So, there I am, thinking: ‘I’m fucking fluent in Danish now.’” Coogan clapped his hands together, rubbing them enthusiastically, ready to go into that kiosk again, living the moment retold.

“So, I go in and say: ‘Må jeg bede om en Mars chokolade?’ and the woman says: ‘Hvad siger du?’

‘Mars chokolade.’

‘Hvad for noget?’

‘Mars …’ and then I said ‘Fuckin’ stupid…’’’

Coogan stood up from the couch and walked up to an imaginary Mars sign: “I fucking started kicking the sign and banging the fucking sign and shouting: ‘Mars! Mars!! Fucking Maaaaars!!!’

‘Nå… Mars’.

“Jesus Christ, I just wanna … fuck this, I thought, I don’t give a fuck anymore. I mean, come on, the whole kiosk was covered in signs of fuckin’ Mars chocolate and she didn’t understand. ‘Nå… Mars’. I mean, seriously, come on. It’s ridiculous. But Danes are not used to foreigners speaking their language and they’re very fuckin’ lazy. What else could it be?”

“I’m here 41 years in Denmark and people still say: ‘Jeg fortsår ikke hvad du siger,’” Coogan admitted, though he actually speaks the language very well and can occasionally drop near-perfect imitations of typical Danish accents when recounting a story.

As for Tim, he told me: “What I found is you have to almost mimic people – how they’re saying it. I think the Danes don’t really care if you get the grammar wrong, but if you don’t pronounce it right, they can’t understand it.”

Social obstacles

“Danes can be a bit standoffish,” jumped in Tony while passing by behind Tim and me. “They keep to themselves, whereas in Ireland, they’d be asking you: ‘Just where are you from?’ Irish people are more curious.”.

“You have to break down barriers sometimes,” said Tim, taking over again. “I find that if I’m with a group of Danish people, even at a school meeting or something like that, people talk to somebody else instead of talking to me. Because I’m not Danish. Sometimes I think I’m just paranoid, but if I’m there with my wife, they talk to my wife. They don’t talk to me. It’s like I don’t understand them or something, you know. So very often there’s that barrier to start with.”

“Somebody said this to me one time: the difference between an Irish person and a Dane is about five beers. It takes them that much to relax and fuckin’ loosen their tongue,” Tony explained.

“But I’m a quiet Irish man,” Tim responded, taking part of the blame himself.

“There’s a shyness there as well, okay, so then you have to do some of the work. They are more inclusive, Irish people. But, you see, I haven’t lived there for a long, long time. And how do foreigners in Ireland feel? Maybe they feel the same as we feel over here. I don’t know that either.”

She died and you never told me!?

For Coogan, another difficulty he could never quite adjust to is the Danish relationship with death. “I can’t handle their attitude to death. I find it very, very cold. There was a paint factory in Lyngby with about 18 Irish and English working there. When a guy died, all the Irish took a day off to go to his funeral. But for the Danes, it’s no big deal, you know. The woman who lived upstairs, for example, I looked after her for years – taking small messages for her and all that. Very frail woman. But she had a medal for the resistance during the war. And I was very proud to do her messages. But when she died, nobody told me! So when the daughter came back to the apartment, I said: ‘Come here … what the fuck, why didn’t you tell me she died!?’ She didn’t really answer. So I said: ‘Who was at the funeral?’ She replied: ‘Me and my brother.’ A war hero! How sad is that? But Danes are just funny like that.”

“Where I come from, there come hundreds, you know. And in Ireland the wake afterwards, that’s a party in itself. In the old days, the body was laid out in the kitchen and people would come in to look at the body and they’d have a drop of whiskey and someone would bring a violin, another would bring an accordion and there’d be a party for two days. This still goes on in the country. In the city they bring the body to a funeral parlour. My cousins, when their father died, they had a wake. This was about ten years ago. People drink all night, there’s tea and food and illegal whiskey called poitin, made from potatoes – it’s very dangerous because you don’t know how strong it is.”

Community spirit

According to Tim, another difference between Ireland and Denmark can be found in the way people relate to their communities: “Here, you pay your taxes and everything is done for. That’s nice and that’s great. But, on the other hand, what it also does is that it stops people from getting involved in the local community. It’s okay regarding your doctor or having your rubbish collected, where not much involvement is needed anyway, but what about your local sports club, for example? In Ireland, people are more involved because they don’t get money from a central fund and they have to fundraise for it or pay for it themselves. So the community spirit in Ireland is probably better than it is here in Denmark. That’s one thing that you could miss.”

Where they are now

Tim is currently still going strong with Kennedy’s … and Tony of course. Regarding the future, he told me: “Well, I don’t know what I’ll do. At least until my kids are grown, I don’t think I’m going anywhere. And then maybe I’ll go to the sunshine. Spain, perhaps.”

Though he’s soon retiring, Coogan is now responsible for feeding the next generation of Danes and expats at a kindergarten. He has cooked for many types, famous people even (has an autograph from Pelé), but children are by far his greatest customers: “The kids … the look on their faces, the joy they get. There are these rockstars that wouldn’t even look at ya, just walk past, thanks and fuck off. But the kids come up and go ‘Tak for mad!’ Okay, I’ll give you one last story, very quick: we were waiting by the elevator with one of the kids. He goes ‘Coogan! Coogan!’ and signals for me to get closer. I bend down and listen, and he whispers to me: ‘You went bald!’ Then he says: ‘Look in the mirror.’ So I looked and went ‘Jesus Christ!’ I acted all surprised and told him: ‘It’s between you and me.’ And he was fuckin’ delighted. The innocence of a kid telling ya that you’re bald! Do you understand? It’s so beautiful. ‘You’re going bald, shhhh, let’s keep it between us.’ And he was so proud – you could see the way he was walking. That we have a secret between us, you know. Isn’t that a lovely story?”

As Coogan’s face lights up with an enormous smile, I see the man he once was, still young-at-heart today.