This column is a declaration of love for Danish libraries.

For years I have had a guilty conscious. I have felt that I was enjoying the paradise all by myself.

Before I tell you exactly how remarkable the Danish libraries are, I must tell you what libraries are like elsewhere in the world, so you have something with which to compare.

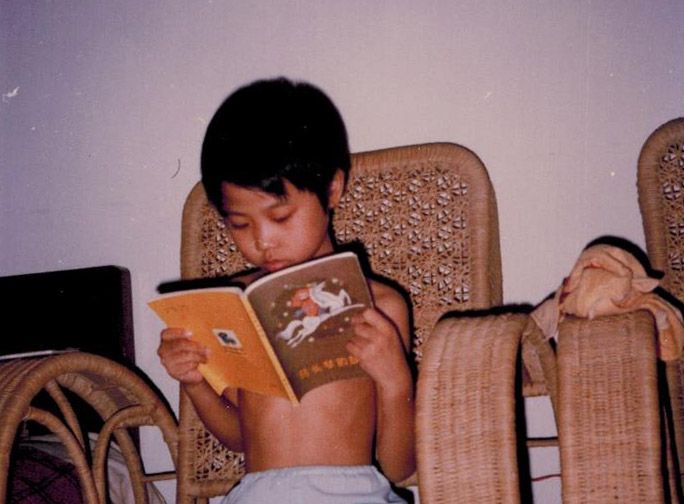

I grew up in different parts of China, both city and land, north and south. One thing all those places had in common was people’s thirst for knowledge. Until 1950s, around 90-95 percent of the Chinese population was illiterate, so knowledge was obtained through oral traditions.

Today, there is less than 3 percent illiteracy in China and reading has become accessible for the vast majority of the population. But because my grandparents’ generation suffered from illiteracy, reading is still considered a great privilege.

Most people take advantage of the joy, freedom and value reading provides. Libraries all over China are well stocked and well visited. However, when it comes to rare books, the number they are able to acquire is limited.

Rare books are typically antiques and limited editions, and there may be hundreds of prints or even fewer, worldwide. Because a large number of people in China seek out those books, the waiting list immense. Scholars, students, authors and others often have to wait months – if not years – to gain access. Most of the time, you will only get a supervised visit with the book for just few hours.

Most authors in China who work with historical fiction would only write about one era, as the research workload would be too heavy otherwise. To learn to read Chinese from the era in question is often the heaviest labor for an author. However, most writers that work with Republican era also work with end Qing dynasty, as the two eras are greatly connected.

Amongst authors in China, we often say that the end Qing/Republican authors are the luckiest and unluckiest of authors. Luckiest, because the amount of material available is astonishing – in both Chinese and all the colonial languages, as China was colonized by many Western countries in that time period.

Unluckiest, because on top of the massive amount of materials to read in Qing dynasty Chinese and Republican era Chinese, there are also mountains of resources in English, German, French, Danish etc.

I’m one of those lucky/unlucky authors, as end Qing/Republican era happens to be my era of preference.

But I view myself as mostly lucky, as being in Denmark provides me many advantages with my research.

The Danish libraries are God’s personal gift to exactly my kind of writer.

When I was growing up, I lived in a former German/British concession in Tianjin. Many times a week I passed historical sites like The German Club, The former Danish consulate, the English church.

This sparked my interest in colonial history, so I learned as many colonial languages as possible growing up. The Danish libraries own many original books from 1800s and early 1900s that are crucial in my research. Most books I order are in English, Danish and Chinese.

Denmark being a maritime country, it has a large number of books about the maritime world history from Qing/Republican era. The Danish libraries also own an impressive amount of books in Chinese about the Qing era maritime history, justice system, culture and literature.

I have been a longtime admirer of the Danish libraries. But my recent research for my upcoming Qing dynasty pirate novel still surprised and amazed me – especially when I found a rare British publication about an English merchant who was held for ransom by Chinese pirates in 1800s. I knew that many libraries in the world (USA, China) only allow supervised visits with this book.

When I told my father (also an author) that I simply ordered this book, and few days later it arrived at my local library and I was allowed to take it home for 30 days, he was blown away. I then told him about this even more rare book printed in 1800s about an English sailor who was kidnapped by Chinese pirates, it arrived at my local library also few days later, and I was free to read the book in that library any time during a 30 day period, as often as I liked.

My father simply does not understand, how no one else seems to want to read such treasures. In my youth, out of necessity, he helped me develop the skill of absorbing and analyzing as much as possible from library book visits of four hours.

The only way this skill would become relevant in Denmark, is if this column made people so interested in historical rare books that they all went out to read them, and caused a significant waiting list.

But not to worry – if that happens, I will write a column about how to develop that skill.