Ali Al Mokdad once led humanitarian operations in Syria. Days later, he was sleeping in a tent, having fled his home, his city, and everything he had built. “I was managing these kinds of projects,” he recalls. “Then suddenly, I was sitting there, learning how to wash my hands.”

That rupture — from leader to refugee — is one of many “red pill moments” that shaped his view of the humanitarian sector. Over the next decade, he lived in 13 countries, working in crises across Afghanistan, South Sudan, Nigeria, and beyond. He held roles at every level — national staff, international coordinator, regional manager, board advisor. And yet, what stayed with him weren’t the positions, but the patterns: the bureaucracy, the distance, the disconnection from people on the ground.

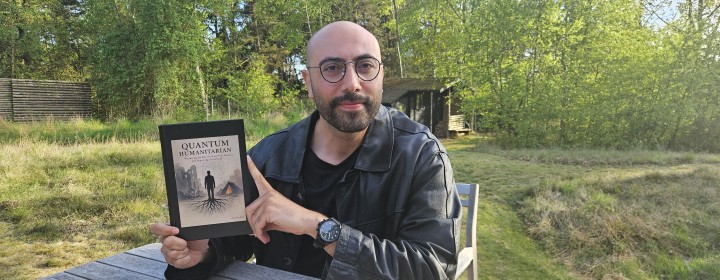

Quantum Humanitarian, his new book, is his response. It’s not a memoir or a policy critique — it’s something more raw. Written in a rare format called “quantum narrative,” the book brings together three versions of Mokdad — past, present, and future — as they reflect, challenge, and remember. It is, in his words, “a love letter to frontliners, a challenge to leadership, and an act of remembering.” But above all, it’s a call to look harder at what we’ve normalized. “Many of us took the blue pill,” he says. “We wanted stability. We wanted to be called ‘hero’ from time to time. But I chose the red pill. And now I want to ask better questions.”

You have worked across some of the most complex humanitarian crises in Syria, Afghanistan, Sudan, Nigeria. For those unfamiliar with your journey, how did your humanitarian path begin and what kept you going through such high-risk roles?

When I started, I didn’t even know it was a job. I was a student in Lebanon, volunteering out of a sense of responsibility, not ambition. I joined a local team and became active with the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement. One day — I was still quite young — I was paid for a voluntary activity, and I felt uneasy receiving a salary for something I believed should be done from the heart. Maybe I was too idealistic. But I would take my salary, pay my rent, cover the basics — and donate the rest. I thought that was the right thing to do.

I started as a national staff member in Syria, and very quickly I ran into the invisible ceiling that many of us from the Global South know too well. I was told I couldn’t lead — that to be a manager, you had to be international. I was removed from technical teams because I didn’t have the “right” degree from the “right” university. I remember saying once that I wanted to apply for a managerial role — and people laughed. But I wasn’t the only one: many brilliant national staff were never given a real chance.

How did the war in Syria change the course of your life?

When the war began, I was displaced from my home. I lost everything. I fled to northern Syria with nothing but a small bag and ended up in a camp, sharing a tent with strangers too afraid to even share their names. NGOs came to train us on hygiene, including how to wash our hands. Just months earlier, I was managing these kinds of projects. Going from a humanitarian leader to a displaced person, was one of the “red pill moments” I write about. It shattered something in me. But it also opened my eyes. Why are our programs designed like this? Why do systems built to protect dignity so often end up taking it away?

From there, I started again. I’ve lived and worked in 13 countries. I’ve led responses in Afghanistan, South Sudan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Iraq, and more. I’ve worked with NGOs, UN agencies, and the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement. I’ve sat in boardrooms and walked the back roads of remote frontline operations. But what shaped me most weren’t the titles or the deployments, it was the people. What kept me going wasn’t ambition — it was conviction. I believed in this work. I still do. And every time I witnessed injustice — the bureaucracy, the discrimination, the distance between headquarters and real life — I felt a responsibility to push back. Because I’ve lived on both sides.

How has this work shaped your identity — both personally and professionally?

Many people think you lose yourself in this job — that you become numb or traumatized by all the things you witness. But for me, it was the opposite, I found myself in it. I started in the sector as a teenager, and my entire adult life was spent on deployments — moving from one crisis to another, never really settling. The first time I experienced what people call a “normal life” was when I arrived in Denmark. It was the first time I had a regular routine, a bit of stillness, a space to breathe. I wasn’t constantly preparing for the next evacuation or thinking about security risks. I still remember the moment I wrote my name on the door of an apartment for the first time in my life. It was in Denmark. And it felt… grounding. Like something I never realized I had been missing. Denmark gave me space. Space to breathe, to slow down, and to sit with the past — sometimes over and over again. And in that quiet, the words that became Quantum Humanitarian finally started to come out.

Coming to the book, you said you have held some leadership roles in global organizations but the book focuses on what you say proximity, presence, memory. How did those frontline experiences shape your leadership philosophy?

I like to call the book a love letter — to frontliners, to humanitarians, to those who stayed when the funding left. First, it’s a love letter. Second, it’s a challenge — to institutions, to leaders — to rethink how we work. Third, it’s an act of remembering. I remind myself — and the people in this sector — of its core values: supporting, empowering, enabling, and being present. I’ve seen the power of those who stay. And I feel responsible for sharing their stories — because I’m one of them. There are so many who go unrecognized, unseen, unheard — yet they’re the ones doing the real work. From my perspective, leadership is one of the most misunderstood terms in the humanitarian sector. I’ve met countless people across countries who held no official title — no “leader,” no “manager,” no “coordinator.” But we followed them. We trusted them. They inspired us through presence, care, and genuine interest in others. I’ve also seen many with titles — director, manager, and so on — whom we followed only out of fear, simply because of their rank. So my book is a love letter to those we followed because they cared — and a challenge to those with titles who remain distant.

Your book doesn’t read like a policy critic or a memoir, it’s more like a part reckoning, part poetry, part call to action. What made you choose this format to express your experience?

This is the first book written in this style about the humanitarian sector. It’s based on a rarely used form called quantum narrative — a technique that first emerged in the 1980s and reappeared in 2006 through a few experimental authors. It explores different scenarios across timelines, which resonates with me deeply, because I always say there are 13 different versions of myself. When people ask, “Who are you?”, my answer depends on the country I’m in. In the book, my past, present, and future selves write together. Most people don’t know this, but I usually write for myself — not to publish. But something shifted, and I decided to share these words with the world. So the three versions of me sat down and wrote. I shaped the quantum narrative with my own voice, inspired by the stories I’ve lived and want to tell. Some readers have told me the book feels like I’m speaking directly to them — sometimes using “you,” other times “I” or “we.” The truth is, they were my reflections. I don’t see myself as an author. I see myself as a storyteller. That’s how I tell stories: I live the different sides of them.

In the book you talk about the collapse of the humanitarian system as we once knew it. What, in your view, has collapsed — and what are we clinging to that no longer serves us?

What’s happening in the humanitarian sector isn’t new — it’s been building for years. The only difference now is that there’s finally a spotlight on it. In my opinion, the sector has reached its limits. First, there’s the financial limit: needs are rising, while funding is steadily shrinking across the board. Second, we’re hitting major operational limitations. This isn’t talked about enough, but if you look at large-scale crises around the world, the sector is constantly battling serious access challenges. Sometimes we can’t reach affected areas; other times, it’s internal inefficiencies. COVID-19 made this painfully clear. When the pandemic hit, we couldn’t deploy people, we couldn’t operate as before — we were stuck. And while that was years ago, the example still stands. If a global or regional crisis were to hit today, would we be ready? I don’t think we are. We’re not equipped to respond at that scale.

Beyond funding and access, what else is holding the sector back?

In my view, we’re facing a bureaucracy crisis. I write about time and bureaucracy in the book because I’ve seen, firsthand, how damaging it can be — not just for staff and volunteers, but for the communities we’re meant to serve. In the drive to professionalize the sector, we built layer upon layer of compliance, procedures, and policies. And in doing so, we created a system that often gets in its own way. We set goals we can’t realistically achieve. First, they haven’t invested in the people expected to carry them out. Second, they haven’t focused on improving operational efficiency in a way that would make those goals achievable.

You talked about following leaders out of fear and invisible leaders. You write also about the illusion of impact without presence. Can you share a personal moment when this illusion broke for you and how that moment changed your understanding of aid work?

There were many moments — in the book, I call them “red pill moments.” In the humanitarian sector, I believe we’re offered two options, like in The Matrix: the blue pill or the red pill. The blue pill is staying inside the system. You build a career, get promoted, collect titles, maybe even join the big panels and summits. Sometimes they’ll call you a “hero.” But the red pill — that’s about clarity. It’s offered to you when something shakes you awake. When you realize, for example, that what’s often called “localization” is just outsourcing risk. When you see local staff and partners taking the dangers that internationals avoid. It’s happened to me many times. I want to share three moments that stand out.

The first was during an evacuation from a country going through a security situation and crisis. Planes were arriving to extract international staff and diplomats. Armed groups were taking over various areas. I was among those moved to a safe haven, along with few other internationals. As we sat in the vehicle, the local driver — from that same country — turned to us and said, “Are you leaving us alone?” I’ve never forgotten those words. They echoed everything we claim — “We leave no one behind,” “We’re here to support” — and they collapsed in that moment. I saw locals clinging to departing planes. I saw our teams left behind. And I heard that sentence: Are you leaving us alone? That was one of my many red pill moments in the humanitarian sector.

The second moment was when I was in another country where we were having long meetings about whether to use blue ink or black ink when signing official documents. Just meters outside our office, children were dying of malnutrition. And we were debating ink colors. That absurd contrast hit me hard.

The third happened during a major earthquake that affected two countries. People were buried under collapsed buildings. I lost friends. I couldn’t reach colleagues. We were leading the response, moving fast, with no time to grieve. In the middle of all that chaos, someone came up to me and said, “I want to go home. I’m stressed. I didn’t have lunch.” That sentence, at that moment, landed like a punch. It exposed a disconnect — not just from the situation, but from the purpose.

What do you do with those moments, once you’ve had them?

I’ve had many. The sector offers you these wake-up calls, whether you want them or not. In the beginning, many of us take the blue pill. We want stability, career growth, maybe a bit of praise, to be called “hero.” That’s human. But I chose the red pill a long time ago. With this book, I hope others will too. We need more moments of clarity — more people willing to look at things as they really are. That starts by returning to our first principles. Supporting, empowering, being present. That’s what this work is supposed to be about. Sometimes the shift begins by simply asking better questions. I believe the sector is going through a leadership crisis and a bureaucracy crisis. We can’t fix those without changing the way we think — and the way we ask questions. I don’t pretend to have all the answers. But I do claim this: I’m still trying to find the right questions to ask.

Many humanitarian actors now work in hybrid setups, often far removed from the communities they serve. Do you think the distance is a problem — or is it something deeper about how we understand responsibility and leadership?

I think the problem doesn’t begin with physical distance — it begins with mental distance. It starts when people build glass boxes between themselves and the communities they work with. Yes, most headquarters are in the Global North, while the majority of operations are in the Global South. There’s a geographic gap. But that’s not the real issue. I once managed a team for an entire year remotely. We never met in person, yet we ran an excellent program. So distance alone isn’t the barrier. The issue is when people place themselves in a glass box — or under a glass ceiling. You may not see it, but it’s there.

From ERP systems to donor compliance, you have also led large-scale organizational reforms. How do we reconcile this technical side of aid with deeply human, almost spiritual reflections you offer in your book?

Technology is not the problem — transformation is. I could repeat that for days. The reason I say this is because I’ve seen excellent systems, software, and tools fail — not because they were flawed, but because of how they were implemented. Digital transformation is becoming yet another form of distance. In some of the organizations I’ve worked in, the people designing digital tools had never spent a single day in a field operation. And many don’t realize that in most humanitarian contexts, there’s often no electricity, no internet, no access. The tools simply don’t reach the people who need them. Even now, if you look at AI — those two letters might have been the most typed letters in 2022, 2023, and 2024. The sector panicked. But the real issue wasn’t the technology itself — it was the bureaucratic layers and organizational silos that blocked meaningful integration. In my book, I tried to bring the soul back into that conversation. The real question is: Where are the people in this transformation? Technology can empower, support, and optimize the way we work — but only if we remember who we’re doing it for. People must remain at the center.

The book is born from lived pain, but also fierce hope. So was writing it a healing process for you or kind of an unburdening?

I think I’ve been writing since I was a child. Writing is how I think and reflect — I do it about many things. This book was just one part of all that writing. But this time, I chose to express my vulnerability publicly. It was partly about expressing appreciation for the people I’ve worked with. It was also a way to challenge other leaders. And it was part of my own reflection process. I always say: I spoke from my heart — to the heart of the humanitarian sector, and to the people in it. I kept it simple, in short chapters, on purpose — to give readers the space to reflect, too. Someone once told me they read the book while waiting at the airport before a deployment. I said, exactly — that was the intention.

To answer your question — I think I’ve been in a healing process this whole time. After each red pill moment, after each deployment, each time I was with people in crisis — there was a part of me that needed to process. And for me, this work also comes with a responsibility. I’ve been given a platform where some people will listen — and that means I have a duty to hand the microphone to those who don’t have one.

If a young humanitarian reads your book, Quantum Humanitarian, today and wants to follow your path, what is the one thing you would urge them to hold on to and one thing they should be ready to let go of?

I’d say — don’t follow my path. Learn from what others have done and what they’ve gone through, but don’t think you need to replicate it. Don’t assume that you have to go to X or Y location to be of value. Try to look at it from another angle. If you want to understand the message of the book, it’s not about you being deployed and leading. It’s about recognizing those who are already leading. As I say in the book: the future has already happened. The future is here — they are leading, they are supporting their communities, they are doing the work. That’s why I don’t believe anyone should try to follow my career path exactly.

What I would say to those who feel called to leadership is: lead with care. Lead with presence. Listen. And always remember — it’s not about you. Look at the leaders who are already there, and learn from them. I criticize the sector because I care about it deeply. I want it to be better. I want us to be efficient — to make the most of every single dollar, euro, or whatever resource is invested.

My hope is that the book offers space to reflect — and to start asking better questions. I’ve received so many messages from people who bought the book, who are thinking about it, questioning it, reflecting on it. I’ve seen it listed as a number one hot release on Amazon in categories like philanthropy, refugee studies, and current events. It’s now a bestseller in Germany, Scandinavia, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. Seeing all that makes me feel humble. But more than anything, I feel glad that more people are becoming curious — that more people want to understand. That’s what matters to me, not the rankings. It makes me proud that people read it and said, this is about me. That they felt seen. That they felt like they were part of it.

Ali Al Mokdad’s book, Quantum Humanitarian, is available in bookstores and online.