On a Store Bededag bank holiday marred by the coronavirus quarantine, few Danes would have given the May 8 celebrations of the 75th anniversary of VE Day much thought – particularly in a country that spent most of World War II under their own kind of lockdown.

But they should be rightly proud, for ranging the blue Mediterranean during the enemy occupation of many of its lonely islands was a young Dane whose exploits became legendary.

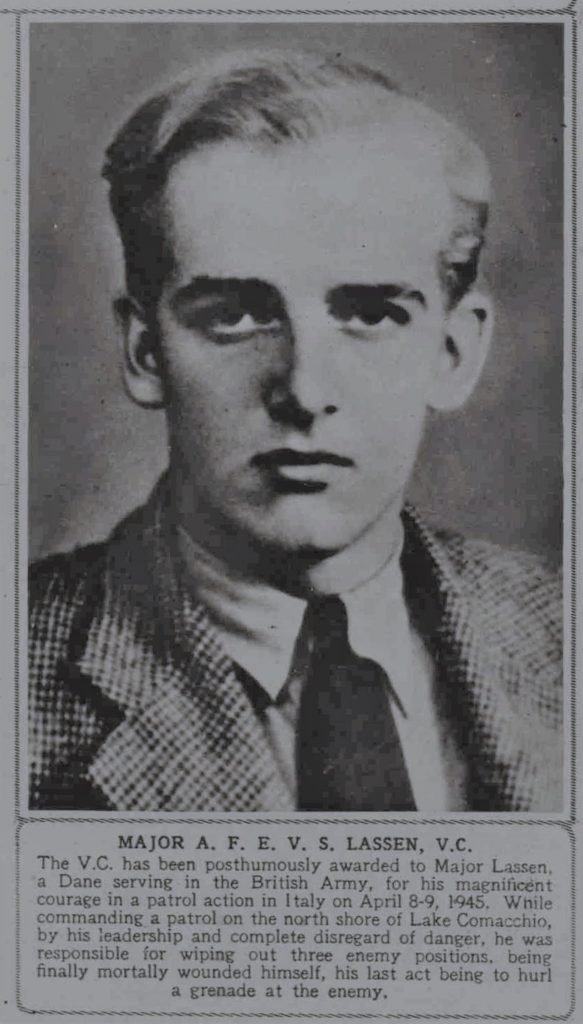

Such was Major Anders Lassen’s impact that he became the only non-British or Commonwealth recipient of the Victoria Cross druing the war.

Modest and charming, this true descendant of the Vikings of old had a vivid personality. Night after night, he would lead his men of the Special Boat Section (later the Special Boat Service) in silent, daring raids – news of which could not be released until the war was over. He sailed in a small Greek caique (traditional fishing boat), hiding behind the rocks in daytime, preparing to strike when the shadows lengthened across the waters.

Overseas during Occupation

Born in 1920, Landers Frederik Emil Victor Lassen lived a privileged life in Nyhavn, but also an adventurous one.

Holidays from Herlufsholm, Denmark’s foremost boarding school, were spent shooting on his father’s estate with his younger brother Franz. They made their own bows and arrows and became so expert with them that they could kill a bird in flight. In the games they described innocuously as ‘Snakes and Arrows’, the weapons were no playthings: the arrows would pass right through a stag and penetrate a tree beyond!

At the age of 17, Anders decided to see the world and he joined the Danish Merchant Navy. A year later the war began, and by the spring the Germans had occupied Denmark while the young Dane was away. He joined the British Army and volunteered as a Royal Marine commando, just like his brother Franz who would rise to the rank of captain. Their father would also fight on the side of the Allies as a captain in the Royal Navy.

Within a month or two of being commissioned, he was awarded the Military Cross “for carrying out special duties with complete disregard for his own safety”. The citation for his actions in Operation Postmaster referred to his “sound judgment and quick decision” when, with all hell let loose around him, he carried on with his job with skill and ingenuity and regained his ship without mishap.

Singing the Führer’s moustache

In an earlier operation on 3 October 1942, Lieutenant Lassen was part of Operation Basalt, a tiny raiding party that sped across the English Channel to the Channel Island of Sark in a small motor launch named ‘Little Pisser’.

They scaled the cliffs and captured some of the German garrison, but while attempting to remove their captives as a propaganda coup, all but one of the Germans broke free, and in the dark and confusion some were shot. The bodies were left on the shore, hands tied behind their backs and the German press claimed they had been executed.

When Hitler was informed, he flew into a rage and a few weeks later (18 October 1942) the ‘Commando Order’ was issued, stating: “Soldiers in demolition groups, armed or unarmed, are to be exterminated to the last man, either in combat or assault. If such men appear to be about to surrender, no quarter should be given to them – on general principle.”

The edict was extended after the D-Day landings in June 1944 to include parachutists, and the Commando Order would later lead to the execution of nearly all of those who escaped from the Stalag Luft III prisoner-of-war camp depicted in the 1963 film ‘The Great Escape’ featuring motor-bike riding Steve McQueen.

Lassen was therefore an obvious choice for the Special Boat Section formed to carry out raids in the Aegean. Before long, a stream of more stories of his incredible adventures were being recounted.

Killing Germans in Greece

In July 1943, he landed on Crete to destroy German aircraft. Accompanied by a gunner, he created a diversion on one side of Kastelli airfield, passing three groups of sentries and answering them in German, claiming he had dropped his rifle. When a fourth sentry had to be shot, the alarm was raised.

The raiders were forced to withdraw under a hail of heavy machine-gun and rifle fire. Back they came, however, half an hour later. This time, they were forced into the centre of the airstrip under the glare of the searchlights. However, they somehow managed to dodge the trap and escape to the mountains where they hid for several days before getting away from the island.

The diversion plan succeeded, and many aircraft and tonnes of petrol were destroyed at Kastelli airfield. Lassen received a bar on his Military Cross.

Barely three months later, the Dane earned a second bar on Simi, one of the Dodecanese Islands. Arriving on a small boat just ahead of the German forces, he sent a corporal to find out from the local people if the water was deep enough for the base ship to come alongside. When the peasants argued among themselves, the impatient Lassen jumped off the quayside in full kit. “All right,” he shouted. “Signal her in. It’s deep enough.”

Lassen’s force was 20-strong and equipped with a variety of weapons including an old German 20 mm gun. The Germans – a hundred of them – came in caiques (sailing ships), and there was no time to build defences. Although crippled by a badly burned leg and internal trouble, Lassen stalked and killed three Germans at close-range.

Throughout the battle he was an inspiration to his men and the few Italian ‘co-operators’ who joined in the fight. The Germans were finally driven from the island at a loss of 16 men killed, 35 wounded and seven taken prisoner. The Allied losses amounted to just one man killed and one wounded. Next day, German stukas dive-bombed Simi.

Lassen, deeply troubled that the peasants were suffering, was genuinely happy when an order to withdraw came two days later. He remained worried about the islanders, though, and when a big German force did occupy Simi, he made risky night trips taking food parcels to the people.

Rough, ready, respected

Such acts of kindness by the supposed cold and callous marauder earned the undying respect of his own men and the affection of the civilian population. Men would follow him anywhere. He had escaped from so many tight corners that they began to think of him as indestructible.

Lassen’s raids on the Aegean islands continued. The enemy never knew where to expect the next lightning swoop. Just before the Germans landed at Samos, Lassen evacuated hundreds of Greek civilians to the mainland.

Unfortunately, the enemy arrived before the operation could be completed. The quick-thinking Dane ordered ropes to be tied together and supported at intervals by boats. Along this lifeline to the mainland many more natives escaped.

Lassen had little time to worry about his comfort or personal appearance. Mostly, he wore a shabby greatcoat, knitted scarf and thick studded boots. The rosettes for his MC ribbon were cut from a cigarette tin. “Rough and ready. But according to regulations, I am properly dressed,” was his wry comment. Food never worried him. He lived off the land or feasted on shellfish prised from the rocks.

A man of few words, it is alleged a post-operation report by Lassen was one of the most succinct ever written: “Landed. Eliminated Germans. Fucked off.”

Slain in heroic fashion

Lassen’s last and most gallant action came during the final stages of the war in Italy, when commandos were given the task of dislodging the Germans from the northern shore of Lake Comacchio in Operation Roast.

Lassen was ordered to take a small patrol across the lake and attack the town to cause confusion and to simulate a major landing. The tiny force set off in canoes. Soon after it landed, the brave men in the patrol had to run a gauntlet of heavy fire. On and on they fought until their ammunition was nearly spent.

Lassen approached to within a few yards of a German blockhouse and called on the defenders to surrender. But a burst of fire from the left struck him down. The dying major told his men to withdraw. They wanted to take him with them, but he ordered them: “Save your own lives, and get out quickly.”

The highest honour

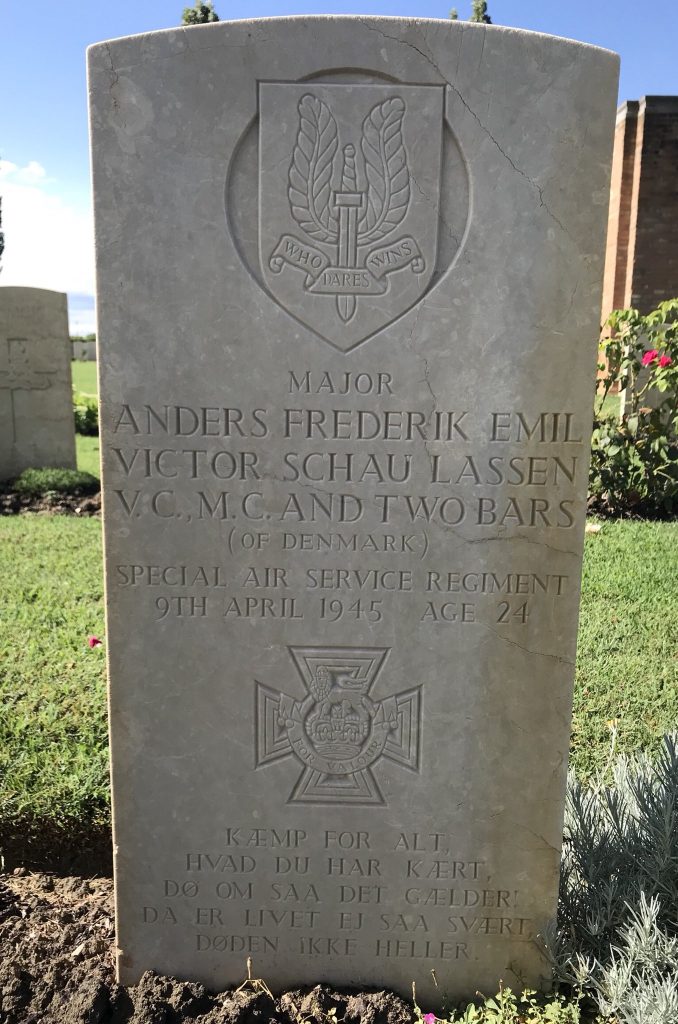

Major Lassen is buried in the Argenta Gap Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Ferrera, Italy beside those who fell with him.

When his award was announced on 8 September 1945 there was a discussion in the British War Office about whether it should stand as he was Danish, although two days later the decision was upheld. A War Office official remarked: “As Major Lassen held a commission in the British Army the [Victoria] Cross has been granted.”

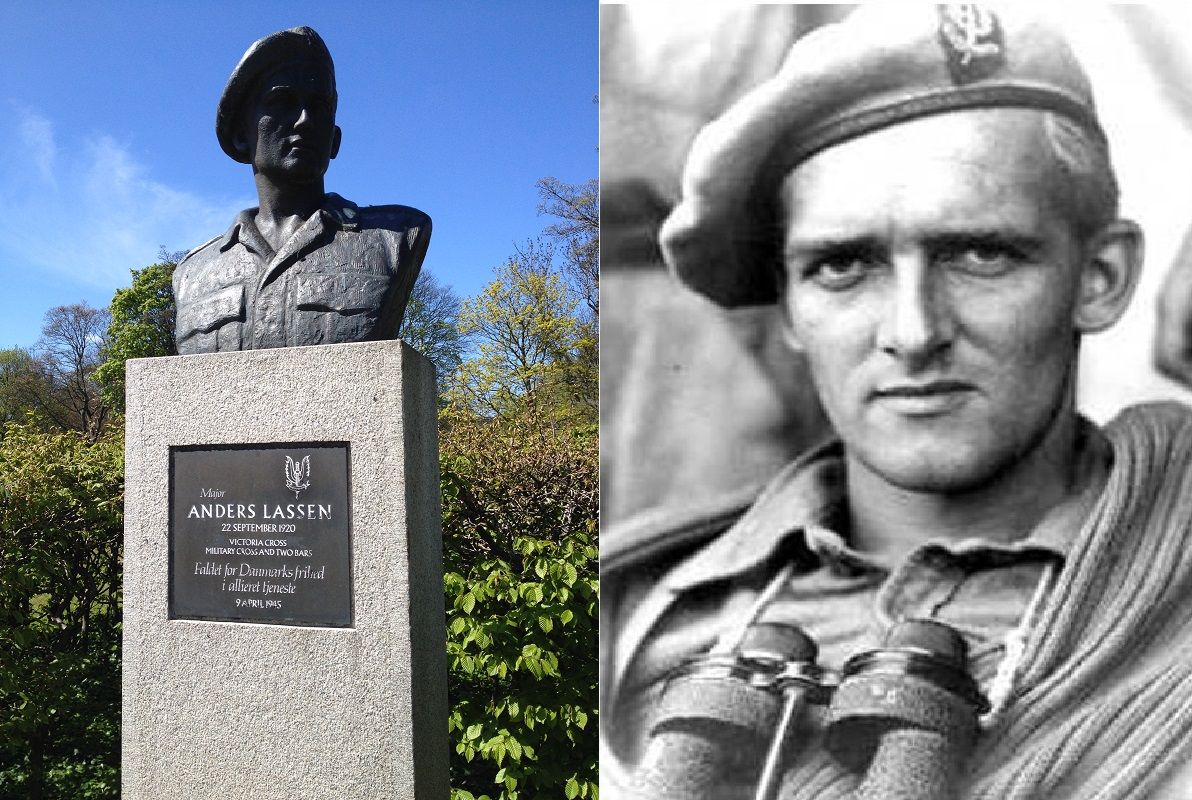

His family, including his parents Emil and Suzanne (who published his biography ‘Sømand og Soldat’ in 1949) and sister (later Countess Bente Bernstorff-Gyldensteen) received the VC and MC and bars from King George VI at Buckingham Palace in December 1945. These medals along with his King Christian X Memorial Medal and the Greek War Cross are on display at the Frihedsmuseet (Museum of Danish Resistance) in Copenhagen. Fittingly there is also a memorial bust dedicated to him in the park christened in honour of his ‘boss’, Churchillparken.