‘Expect the unexpected’ was the slogan when the pandemic arrived. We had not, or at least in the queen’s reign, seen anything like it.

Two years and several mutations later, we are still living with it, but we are not worried anymore – more irritated than anything. But normal life is back, and the masks are gone.

Beast in the east

President Putin’s mask has gone as well: we can see his true face in Ukraine now. How it ends remains to be seen, but it has turned our attitude towards Russia upside down.

When the Cold War ended and the WWII generation in Denmark could finally relax, we adopted a mitigating attitude towards Russia – long overdue, we optimistically said at the time.

For almost three centuries, Russia had been a dominant factor in Danish politics, arguably from the moment Peter the Great famously rode up and down the Rundetårn in 1716, and in 1945 they took a foothold when its troops occupied Bornholm for a year following the end of WWII.

Denmark wisely ended up in NATO, but Russia remained a threat, unseen but still feared by generations of conscripts from their positions at Køge Bugt, guarding against a possible invasion from Warsaw Pact forces. This was a very real possibility, as such plans were confirmed shortly after the Soviet Union collapsed 30 years ago.

These are unusual times

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a huge all-round shock. Tzar Putin is attacking to paralyse an independent nation of 40+ million people, and very few of them are on his side. Of the 6 million Russian-speaking minority, only 35,000 are pro-Russian separatists. They hold a strong position in the Donbas region in the very east of the country, but it won’t sway the result.

Already the invasion has had a major influence on the political theatre. Parliament has given standing ovations to the Ukrainian ambassador – not too dissimilar to the one given in the US Congress following the State of the Union address. These are unusual times – to put it mildly.

On top of that, Denmark has presented Ukraine with hundreds of anti-tank rockets and ripped up its asylum policy to open up the country to Ukrainian refugees and instant integration.

Looking ominous

The support for the Danish actions was unanimous, bar some noise from Enhedslisten where some old-timer communists expressed some sympathy for Putin, but they were voted down, so united we stand.

It reminds older Danes of the attitude in 1956 when the Hungarian refugees poured into the country – the door was opened to many, of whom a fair number are still here and well.

NATO does not want a confrontation with Putin, but Russia is not what it thinks it is, and the sanctions imposed by the rest of the world will change the game.

It has already jump-started a rise in the defence budget in Germany and probably in Denmark too. They and others quickly want to become independent of Russian energy – an export shortfall for the gas giant that will be hard for it to sustain.

It is early days, but Putin may have really overstepped the red line this time. An exit strategy will be on his mind when the Russian people realise that it is not a reality show but a tragedy.

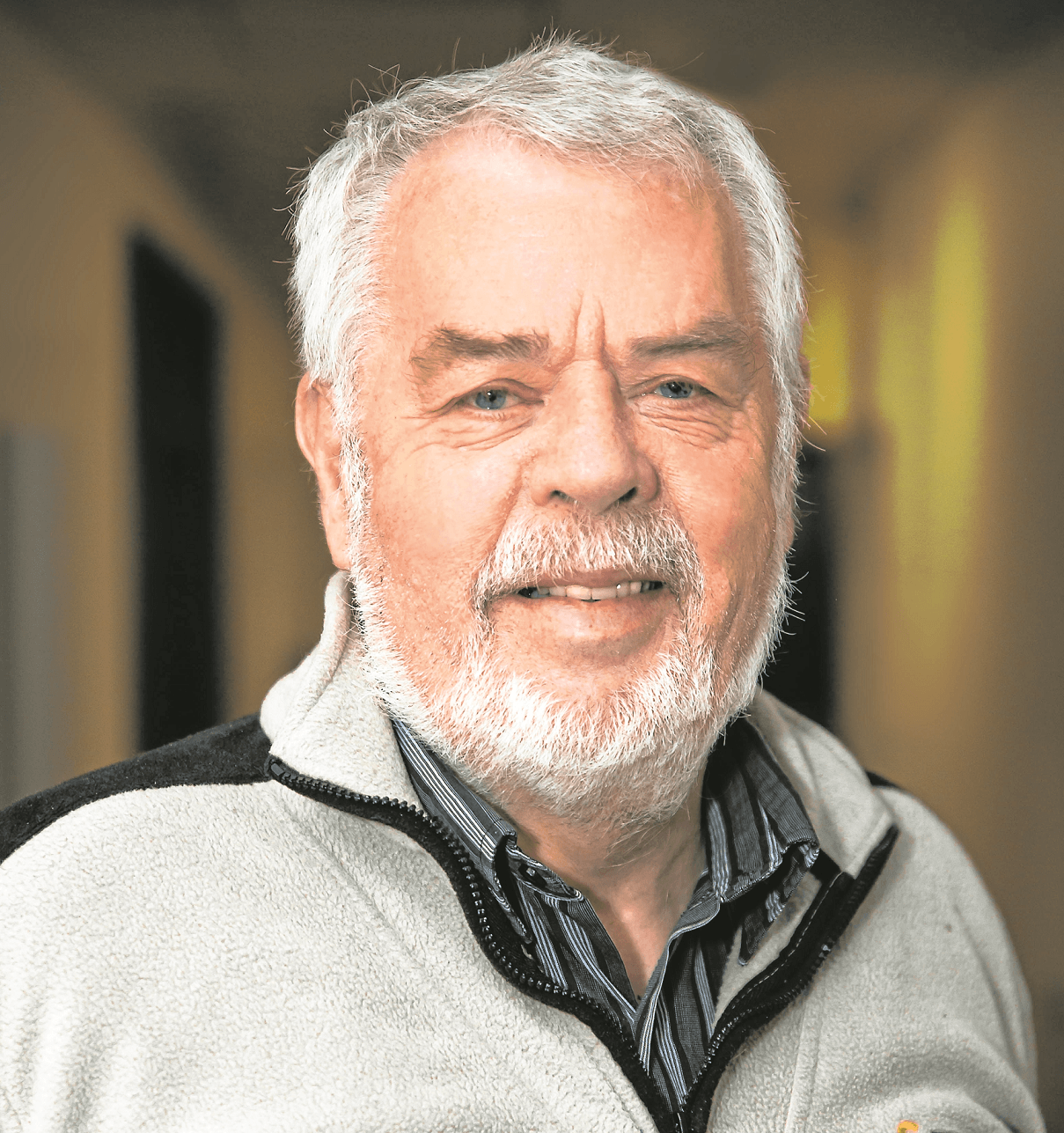

Ejvind Sandal

Copenhagen Post co-owner Ejvind Sandal has never been afraid to voice his opinion. In 1997 he was fired after a ten-year stint as the chief executive of Politiken for daring to suggest the newspaper merged with Jyllands-Posten. He then joined the J-P board in 2001, finally departing in 2003, the very year it merged with Politiken. He is also a former chairman of the football club Brøndby IF (2000-05) where he memorably refused to give Michael Laudrup a new contract prior to his hasty departure. A practising lawyer until 2014, Sandal is also the former chairman of Vestas Wind Systems and Axcel Industriinvestor. He has been the owner of the Copenhagen Post since 2000.