A woman hunches over a lifeless body, the muscles in her left arm taught and straining at the weight. Just below her shoulder, the two bodies seem to stretch and merge into each other. It is an almost impossibly visceral image, the woman’s mouth is fixed to the chest of the body as if to connect with the very essence of any remaining life. This is a mother holding her child. It is the ultimate display of despair, and yet it is beautiful. It is resonantly human.

Käthe Kollwitz happened to be born just as the wheels of change, chaos and death had begun to turn again in Europe. Mensch, an exhibition spanning the breadth of her life and the first solo show for the artist in a Danish museum presents the gaze of the artist as nakedly humanist, committed through everything to capturing the human condition at a time of great change.

Earlier pieces find focus through historical events. In works like A Weaver’s Revolt (1893-97) and Peasants War (1902/3) Kollwitz pulls faces from history into her present, making their suffering contemporary in a way that continues to resonate. These images are deliberately raw and unpolished, stripped of sentimental heroism and triumph. In doing so, she gives a voice to the voiceless.

Much has been written about her life and the loss of her son in the opening months of the First World War, and death stalks every corner of the exhibition, alongside the security guards. The room melts away in the face of Woman with Dead Child (1903), presented in multiple iterations on one wall. The seats facing them feel like church pews. Resting on these pews are headphones encouraging visitors to focus on the artwork. It’s a guided meditation on tenderness and death, and a reminder that images just like these are on the news ad infinitum, dressed in modern clothes and constantly relevant.

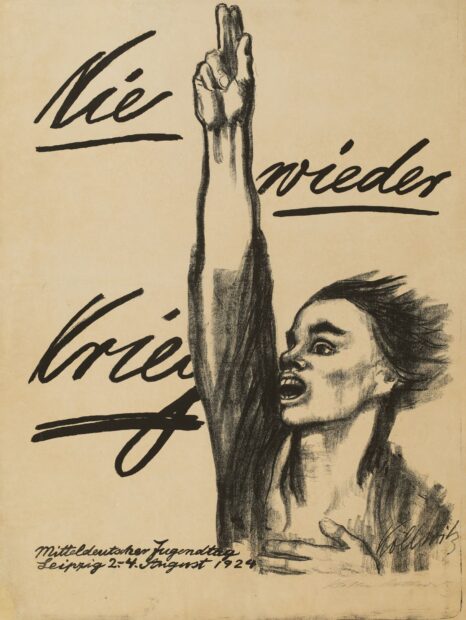

Kollwitz never engaged in party politics, but throughout her work the line between social and artistic effect is blurred to a point of almost complete abstraction. SMK balances this delicately, most clearly when one of Kollwitz’s most enduring images- a lithograph protesting for pacifism (Never Again War (1924)), is framed behind a bronze relief of a mothers embrace, Mother with two Children (1932-36).

Seen together, the sculpture suddenly feels more political. The power and strength of the mother melting her children into her is a powerful study in both love and the fear of loss- a sheltering from a world full of winter or harm.

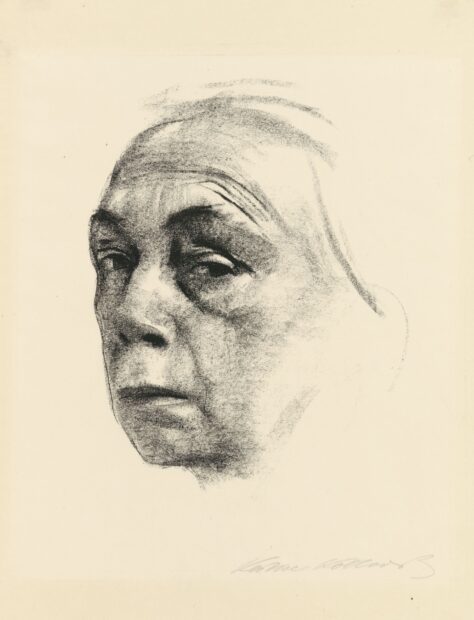

In the adjoining rooms, we finally meet the artist, wearing the same worn eyes of so many of her subjects. You wonder how much of herself was bleeding into her work, or how much of her work bled back in return. But these are also focussed eyes. “It is my duty to voice the sufferings of men” she wrote in a diary entry in 1920, “this is my task, but it is not at all easy to fulfill”.

The exhibition finishes with a sculpture, and perhaps a gasping sense of redemption or hope.

Mother with Child over her Shoulder is tender and naturalistic. A mother struggles to control a child filled with curiosity as it climbs precariously over her shoulder. In her form we see no understanding of danger in a child again merged partially into an embracing mother. It’s a reminder of the core of her focus- a timeless tender human expression, in pain and in love, and a call ultimately to peace and compassion.

Käthe Kollwitz- Mensch is at Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) until 23rd February 2025