While much has been written about the famous British East India Company, few realise that the British version was one of many private European companies responsible for establishing colonies around the world. The French, Portuguese and Dutch had their own versions as did Denmark, with the Danish East India Company and Danish West India Company responsible for claiming parts of the Caribbean, India and Africa, first for profit and then for the crown.

It is a testament to the power of capitalism that private companies could actually conquer and settle whole territories. This is exactly what the East India companies and their many variants did. Even at the time, the actions of these companies caused concern to their national governments, eventually leading to their dissolution or nationalisation. The concern was well warranted. If you can imagine Nike raising its own army in order to invade Indonesia, simply to gain better trading conditions, you get an idea of what these companies did and the profits they reaped in doing so.

The Danish East India Company was established in 1616. Following approval by Christian IV, it focused on exploiting the lucrative trade opportunities that India offered. After taking some years to raise the necessary capital, the company was ready to send forth its first expedition. A small fleet consisting of four Danish vessels left Copenhagen in 1618.

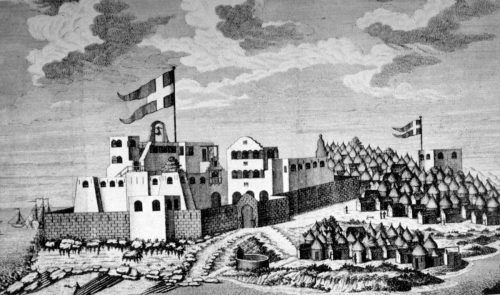

Although Ceylon (modern day Sri Lanka) was the intended destination, hostility from the Portuguese led to the 24-year-old Danish captain, Ove Gjedde, taking the fleet to the Coromandel Coast instead. In October 1620 he arrived at the court of the Nayak of Tanjore. After successfully negotiating a trading partnership with the local ruler, the Danes were given permission to erect Fort Dansborg in the town of Tranquebar.

Rough goings

Nestled on the south-eastern tip of the Indian subcontinent, Tranquebar would become the home of the Danish colonial governor, known as the ‘Opperhoved’. Due to the relatively small size of the Danish colony and lack of merchant vessels, the colony failed to prosper and it was only through a combination of luck and resilience that the colony managed to survive. At one point disease and desertion decimated the Danish garrison so much that only one Dane survived. After it became clear that the colony was commercially failing, unwilling to lose face, the Danish crown took possession of the colony in 1779 before selling it to Britain in 1845.

Like its sister company in India, the Danish West India company was a private corporation designed to extract maximum profit from the weakness of the local population. The company was formed in 1659 and began operating on the islands of St Thomas (1672), St John (1718), and St Croix (1733), a group today known as the US Virgin Islands. These small Caribbean islands, known as the Danish West Indies or Danish Antilles, would provide a steady flow of income from the sale of sugar, becoming part of the infamous ‘triangular trade’ that would see slaves transported from Africa to colonies in need of labour.

Despite benefiting from the slave trade, the Danish colonies in the Caribbean did not maintain their profitability, leading to the Danish government assuming control of the West India Company in 1754. After unsuccessfully attempting to revive it, the company was liquidated in 1776, leaving the islands as a strain on the crown purse until they were sold to the United States in 1917.

Dominating slavery

Another area of Danish colonial profiteering came in the form of the ‘Danish Gold Coast’, an area of modern day Ghana. In 1663 the Danish West India Company made its presence felt along the coast, eventually seizing key forts from arch rival Sweden. After renaming one Christiansborg, the Danes soon built four more, of which Fort Fredensborg was of key strategic importance.

After some more trouble with the Portuguese, the Danes focused on the Volta River delta, soon dominating the region and its lucrative slave trade. By controlling key slave ports and by having Caribbean colonies in which to use the labour, the Danish West India Company enjoyed some years of profitability; however, as the emancipation movement gained momentum this soon ended. The forts were eventually sold to Britain in 1850.

As protests continue around the world against corporate greed, it pays to remember the bad old days when companies not only lived for profit but employed armies in order to extract them. While it’s true that private companies continue to exploit foreign workers under the guise of globalisation, we should be thankful that at least some of their powers have been curbed, even if their motives remain the same.