Two hundred and eighty seven years ago, Vitus Bering reached America by travelling from the west, just as Christopher Columbus had done by travelling from the east. His legacy lives on in atlases: Bering Island, the Bering Sea (the section of Pacific Ocean between Asia and America to the north of the Aleutian Islands) and the Bering Strait, which links the Pacific and Arctic oceans. All of them are named after the doughty Danish explorer from Jutland.

It was during a Russian Expedition in 1728 that Bering discovered that Russia and Alaska were not joined together but were in fact separated by a 96 kilometre wide strait now named after him. At the same time, he was the first to reach the Gulf of Alaska and plot the Alaskan coastline, and discover the Aleutian Islands.

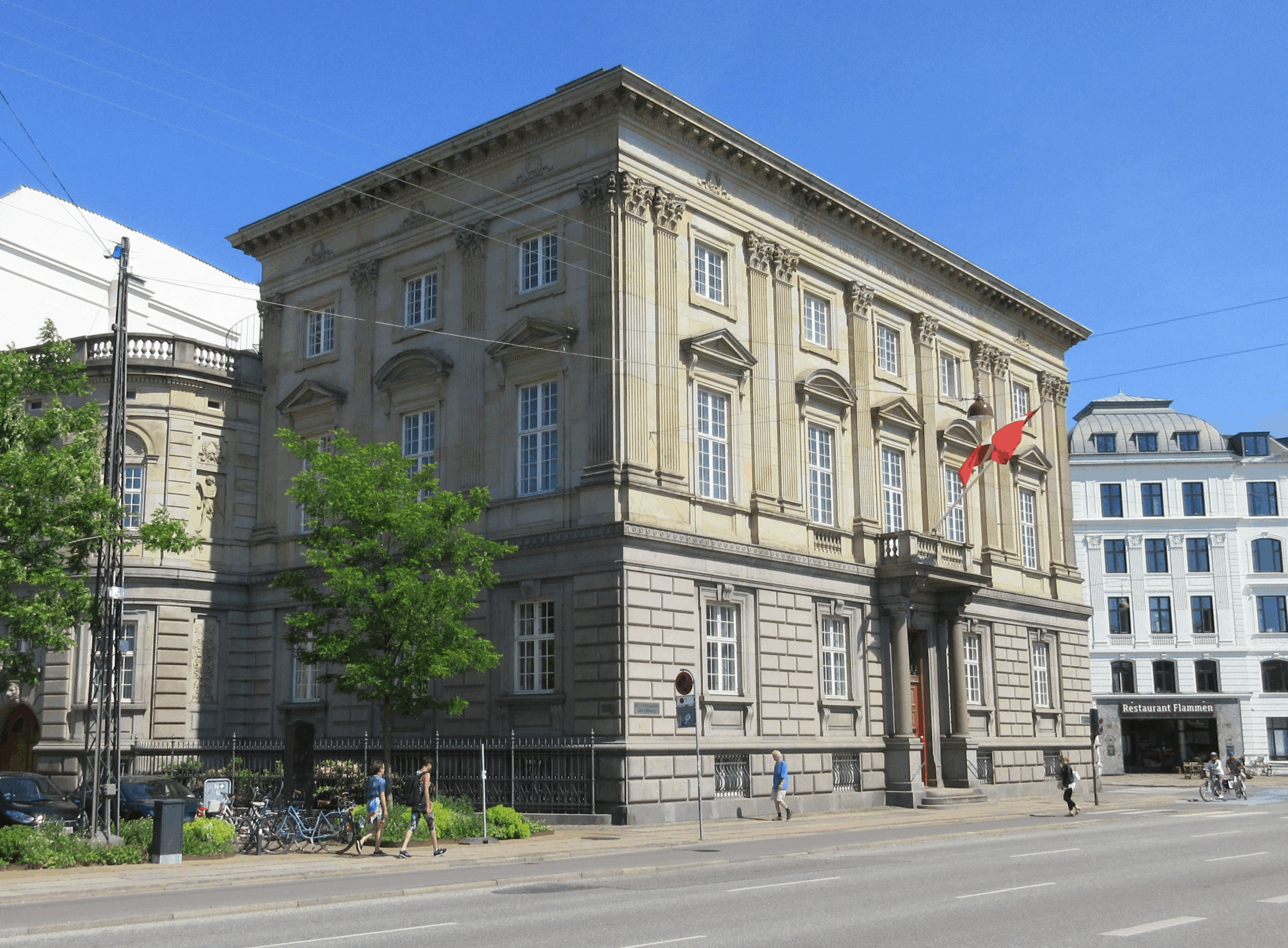

At the age of 22, Bering, with a voyage to India behind him, enlisted in Tsar Peter the Great’s Imperial Russian Navy. He would only see his native Denmark one more time during his life, during a short visit to Copenhagen in 1715. After fighting in the Swedish Wars (on the Russian side) Bering was put in charge of the mission to chart the easternmost extremities of the Russian realm – the idea of Peter the Great and the Russian Academy.

Gruelling voyage

The expedition was one of the longest and most arduous ever planned. Its primary aim was to ascertain whether or not the continents of North America and Asia were linked, a discovery of major consequence for Russia’s later role as an East Asiatic power.

After a two year long, 9,000 kilometre trek from St Petersburg to Ochotsk through some of the grimmest, coldest and bleakest areas of icebound Siberia, Bering’s party set up base in the Kamchatka, where they built the two-masted St Gabriel in which they sailed northwards in the summer of 1728. Another Dane, lieutenant Morten Spanberg, was second-in-command of the 44 man crew on board.

After copiously charting the coastline of northern Siberia, the Danes, observing the coast disappearing to the east in the mist, and convinced that Asia and America could not be connected, felt that they had accomplished their mission, and, fearful of the imminent prospect of winter storms and ice, turned back to Kamchatka.

Blasted in P’Burg

Back in St. Petersburg in 1730, Bering’s failure to fully complete his mission and actually land on the American coast met with strong criticism, but this did not deter the Russians from entrusting the Dane with the command of a second Kamchatka expedition. It was to be the most ambitious such venture yet with 10,000 participants, and began in 1733 with the express aim of finding and mapping the west coast of America.

It was a tired, frustrated and scurvy-ridden 60-year-old Bering who set off in June 1741 from Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka peninsula aboard his new Brig, the St. Peter, flagship of the Alaskan expedition. Accompanying him was the sister ship, the St Paul. The two brigs, named after twin fortresses in St. Petersburg, set an easterly course for Alaska. On 21 June, they lost each other in the north Pacific, never to meet again.

The St. Paul, under the command of a Russian, Alexei Chirikov, first sighted Alaska at cape Addington, on 15 July. In the ensuing days the two boatloads of men sent ashore to reconnoitre the newly discovered territory never returned, after falling victim to savage tribes; after which the St. Paul headed back home.

Shipwrecked on return

Bering’s St. Peter reached Kayak island further to the north in Alaska, near today’s Anchorage, on 18 July, the crew setting eyes on mighty snow-capped Mount St. Elias looming up before them. After a one day stay on the American coast, Bering turned back, zig-zagging a course past Kodiak Island and other islets to the south of the Alaskan peninsula before passing through the Aleutians.

After suffering incredible hardships on the difficult voyage back, the St. Peter was finally wrecked off what is today known as Bering Island, 185km to the east of Kamchatka. It was on this mountainous outcrop that Bering died on 8 December 1741, along with 29 of the St. Peter’s 78-man crew. The survivors finally reached Avacha Bay on the Kamchatka peninsula in August 1742, in a makeshift vessel made from the wreckage of Bering’s proud brig, after a 15-month ordeal.

In 1991, Bering’s grave and those of five seamen were unearthed at a remote site on Bering Island, and the remains transported to Moscow for forensic investigation, enabling scientists to recreate a bust of the explorer, before his bones were reinterred in their original burial place.