And to think we thought fake news originated during the 2016 US presidential campaign, and that spoof news was invented by the BBC’s flagship current affairs program ‘Panorama’ in 1957, when it fooled thousands into believing spaghetti was a plant grown in Italy. To be fair, it was back when the banana was still considered an exotic fruit, although it was on April 1 …

No, set your clocks back to 1904 – yes, over three decades before Orson Welles’ famous ‘War of the Worlds’ radio broadcast in 1938, which caused panic across the United States – and how a now infamous advert for a coffee house on the front page of Politiken caused panic by deliberately masquerading as a serious news story about extraterrestrial life.

Some 101 years later, the publication of the Mohammed Cartoons in Jyllands-Posten would go on to provoke a backlash across the Islamic world, but in its own way, the reaction to the advert for Dalsgaard’s Coffee Company was no less fervent amongst the religious community in Denmark, with its creator even receiving a death threat.

A world in tune with sci-fi

In the long and prestigious history of Politiken newspaper, it has never received as many complaints as when the ‘Telegram from the Moon’ article appeared on its front page on 4 August 1904. The incident served as a warning to newspaper editors all over Europe that disguising advertising as serious news can have far-reaching consequences.

It was an enthusiastic worker at the advertising bureau Sylvester Hvids who was responsible for the out-of-this-world promotion. Charged with designing an advertisement for Dalsgaard’s Coffee Company on Højbro Plads, the idea of a fake newspaper article was suggested, and all parties involved agreed it was an excellent idea.

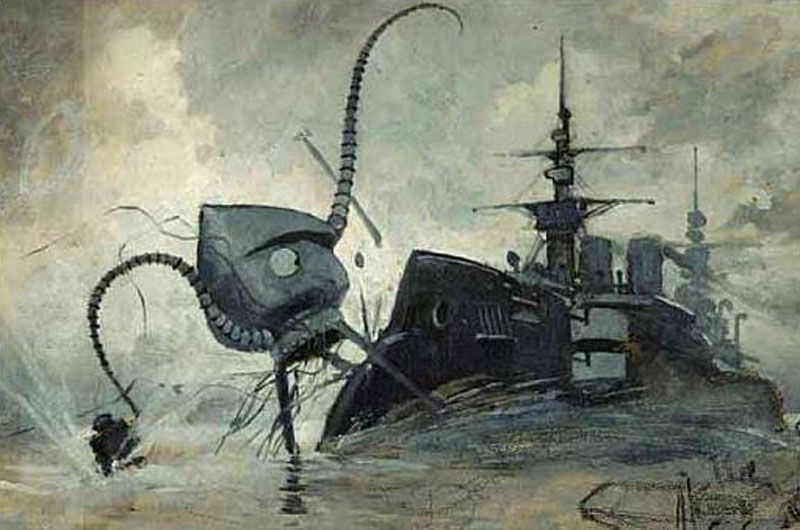

For a topic, the bureau opted for a sci-fi angle. Thanks to Jules Verne (‘A Trip to the Moon’, 1865) and more recently HG Wells (‘The Time Machine’, 1895; ‘The War of the Worlds’, 1898), it was a popular genre. And thanks to films like Georges Méliès’ ‘A Trip to the Moon’ (1902), the world was waking up to its suitability to moving pictures. As far as the public were concerned, therefore, the sky was no longer the limit.

A telegram from where?

Nevertheless, it must have been a surreal experience to be greeted by the headline and lead-in “Revolution in Space” – “History-making telegram arrives at astronomy observatory. Connection established between the Earth and Moon.”

The story began with the utmost gravity: “Since yesterday morning at 9:16 US time, it can be confirmed that the Earth is no longer the only inhabited planet in the universe. Moon-dwellers have made direct contact with our planet via optical telegram.”

A dramatic description of the methods used by the observatory – apparently situated on a snow-covered volcano in Mexico – then followed, explaining how the so-called optical telegram was received. However, as the article continued, its credibility faded, as it became increasingly nonsensical, culminating in talk of the prophet Elijah’s “mysterious disappearance in a huge, flying train rising up in the direction of heaven”.

Then came the pay-off: “The telegram … is written in an ancient script that by a remarkable coincidence can be understood in Danish when you read it backwards.”

The so-called first message to mankind, when reversed, read: “We, the moon-dwellers, have Dalsgaard’s fine coffee shop in our sights.”

Think before you preach!

It would be a mistake to assume that everyone had a long attention span in 1904! There could be no doubt about the article’s lack of credibility to anyone who finished it, but skimmers and presumptive readers were as common then as they are today.

Sophis Müller, a priest from St Thomas’ Church in Frederiksberg, was among the many readers taken in by the article. And alas for the naïve churchman, this was a Sunday! Upon reading the first part of the text he flew out of the door in great haste to bring the “amazing news” to his Sunday congregation. This he did, proclaiming loud and clear from the pulpit that the messages currently being received in Mexico could signify the end of the world and that Judgement Day was imminent.

Those in the congregation who had not read the article stared at the priest in open-mouthed bemusement. Others, stifling their ever-growing guffaws as the by-now over-excited parson urged his flock to repent all their sins, played along. A recording of the out-of-this-world sermon has survived until the modern day.

“Be grateful that we know entirely the divine dispensation of heaven,” Müller boomed. “Because now it is granted to us to walk hand-in-hand with our brothers from the Moon.”

There goes ‘Moon-Müller’!

Thankfully the poor pastor was not allowed to continue to the end of his most famous sermon. When talk of interplanetary travel began – a forerunner of scientology perhaps – a merciful member of the flock discreetly tapped him on the back for a quiet word.

News of the parson’s blunder soon spread, and it is said that from that day he was never called any other name than ‘Moon-Müller’.

Despite the news being a major publicity coup for the coffee house, it did not escape the wrath of other irate citizens who had also been caught out by the story. One angry reader reportedly threatened to visit the person responsible for the ad and “lead him in the direction of heaven”.

Despite the publicity, the ad campaign was pulled shortly afterwards, and the furore led to the bosses at Politiken newspaper having a major rethink of their future editorial policy.