Since the agricultural and industrial revolutions, man’s impact on the landscape has been a subject of interest to artists. So it seems extremely apposite in these days of global warming and climate change that we should re-examine the changes humankind has wrought on their natural surroundings from an artistic perspective.

A new exhibition at the Hirschsprung Collection attempts to do just that. It takes as its springboard the period scientists term ‘Anthropocene’ – the current geological age viewed as the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.

Although this started rather earlier with widespread tree felling for fuel and to build ships, it accelerated rapidly in the 1800s, so the exhibition concentrates mainly on works from that period up until the 1920s, but with a contemporary twist added.

It’s also a sobering thought that at one time the museum itself was situated outside the Copenhagen city boundaries and was almost in the countryside.

Earth and the landscape

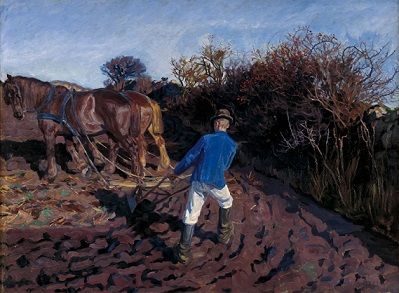

In any case, the exhibition kicks off with a powerful start. In Peter Hansen’s dynamic painting ‘The Ploughman Turns’ (1900-1902), you can almost feel and smell the newly-turned earth. Earth colours predominate – apart from the ploughman’s white trousers and blue coat, which are mirrored in the blue sky above with its skeins of white cloud.

Hansen’s picture is placed close to Frederik Vermehren’s ‘A Sower’ (1859), although that picture seems to show a more romanticised view of the countryside, with the sower seemingly lost in contemplation in the soft morning light and an idyllic landscape in the background.

Enter science

Close analysis of LA Ring’s ‘Landscape, Mogenstrup’ (1888) has detected traces of corn dust and soil in the paint.

It was also around this time that the teachings of the Danish geologist Johan Georg Forchhammer began to influence artists. As well as nature forming the basis for the actual paints they used (i.e chalk for grounding a canvas), Forchhammer’s theories regarding the formation of the Danish landscape were known among artists.

A number of Danish painters were fascinated by the chalk cliffs at Møns Klint, and works by CW Eckersberg and PC Skovgaard are featured showing these dramatic chalk formations.

Digging up the past

Another science that exercised the minds of artists of the time was archaeology. Denmark has a rich heritage of remnants from the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age, as educated men began to map them and excavate the past as part of forging a new national identity.

Along with some fairly fanciful ideas regarding the appearance of these primitive Danes, which hark more towards classical models than reality in Denmark, the exhibition features a number of pictures of barrows and other archaeological features.

Some of these can be seen in the sketches and paintings of Johan Thomas Lundbye. A Danish nationalist, Lundbye was on a mission to record the Danish countryside before it disappeared, although he was not averse to embroidering the truth sometimes. Unfortunately, he was unable to complete his project, being killed in the war with Prussia in 1848 aged only 29.

Darkest Jutland

In the section of the exhibition entitled ‘The Art of Mapping’ there is a salutary reminder that much of the art produced was Zealand and Copenhagen-centric, because that is where the majority of art schools were.

Jutland was still very much ‘terra incognita’. Seeing Jutland, the geographer Edvard Erslev said he felt “almost as if in a desert, with the heather taking the place of the sand”. Lundbye also titled one of his drawings of the heathland ‘Memory from Hell’.

This state of affairs was only really changed by the advent of the railways and proper roads – and that came much later to Jutland than Zealand.

A pride in progress

The enormous growth in agriculture and economic prosperity it brought is also reflected in art. In Harald Slot Møller’s ‘Danish Landscape’ (1891) the ears of corn in the foreground are in relief and made of gilded cast iron. Hammershøj’s ‘Landscape, Falster’ (1897) shows the flour mill – one of the technological wonders of the age – standing proud and central in the landscape.

One of the final rooms in the exhibition is entitled ‘The Productive Landscape’. Here, a large picture by LA Ring, ‘Tilers’, shows a farmhouse under construction in the background with a tiled roof well underway. The foreground is dominated by the workmen who are actually making the clay into tiles, so the whole process is illustrated in the picture.

Conflicts looming

However, conflicts were looming and a number of people were uneasy about the way things were heading. Købke’s ‘Scene Near a Limekiln with a View Towards Copenhagen’ (1836) shows an idyllic farmhouse with grazing cows and meadows in the foreground, but in the background the skyline of industrial Copenhagen is looming – a portent of the future.

The theme of encroachment and change is continued in the contemporary input provided by Rune Bosse and Camilla Berner.

Berner has a series of works on the theme of invasive species, involving modern photos as well as dried and dissected plants placed in displays harking back to those familiar from old-fashioned museums. One of these interlopers is the Japanese Knotweed, originally imported as a decorative feature but now feared by gardeners for its ability to spread and being impossible to remove.

In addition to the art it is also possible to access podcasts, with input from weather forecaster Jesper Theilgaard, TV sustainable farmer and broadcaster Frank Erichsen and the geologist Minik Rosing.

Taken as a whole, this exhibition provides a welcome artistic impetus to a debate that has mostly been conducted in the political and economic arena.