The same year Károly Németh left Hungary, a girl named Beáta Bella was born in Szirák. Twenty-eight years later, this girl would go on to meet a Danish man with the purpose of honing their German skills together – he was on a visit and a friend set them up. They would eventually fall in love and move to Denmark together. This is where their son, Daniel Fabricius would be born – in Kolding, Jutland.

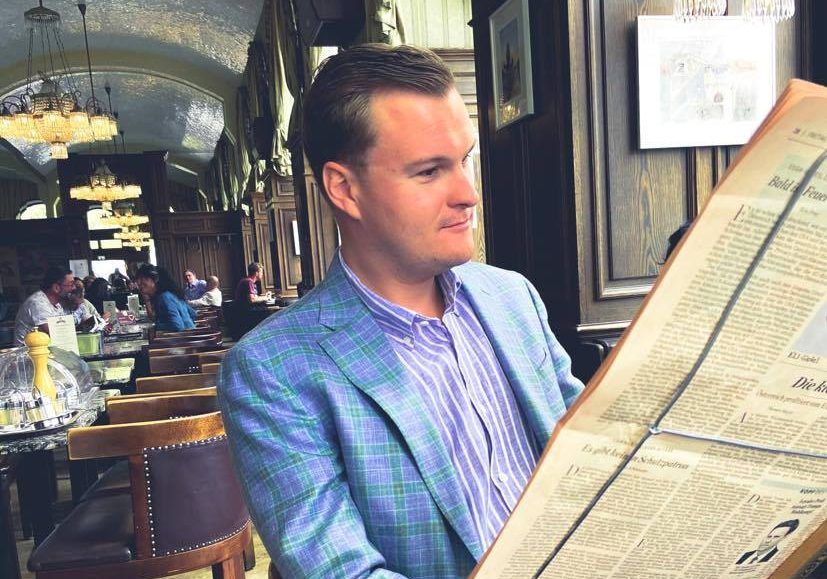

I met Fabricius at the Danish-Hungarian Association where he’s a member of the board. He is also an economist and the former vice president of Young Conservatives Copenhagen (Konservativ Ungdom I København). “I have a fire in my belly, I can’t stand still. If I’m interested in something, I want to be active in it, pursue it further.”

Though Fabricius grew up in Denmark, he speaks Hungarian – that is how we talked when I called him one chill Thursday night.

Tell me, how was it growing up as a half-Hungarian, half-Danish kid in Denmark?

I always felt I was different from most of my Danish peers. I saw things from a different angle. For example, the position of the family in Denmark. In Hungary, the family is more of an institution. It carries a greater importance. And I have always gravitated more towards that approach.

Can you give me a concrete example of this difference between conceptions of family?

For example, it wouldn’t be uncommon to pay rent – however symbolic it may be – to your parents after turning 18. I don’t think that would happen in Hungary.

And there were other differences too: I’ve never had the same excess admiration for the US as many of my compatriots. America is, of course, an interesting and large country, but we have so many nations with older and richer histories around us. I was more interested in exploring those instead of visiting New York high-rises. I think this comes from my bilingual background and the Central European culture running through my veins. Take a look at Russia, Poland, Hungary or Austria. These are countries that have had enormous importance in European history. And they’ve been around much longer than the US. Yet, Danes know very little about them.

You often write political pieces and take part in debates. Can you give me an example of something that you had to explain to a Danish audience – perhaps something that’s misunderstood in Denmark about Hungarian politics?

Or take the fence at the Hungarian border. The thing about that is: Hungarians might put a fence at the border, but in Denmark there are also fences, metaphorically speaking, but they’re in front of homes, not at borders. Hungarians say: ‘We will only let those in our country who enter legally and who are willing to contribute to, and be part of, our society.’ But once they let you in, Hungarians actually let you in – though a foreigner at first, you will become one of them. Danes, on the other hand, believe that they are very accepting of everybody because they let them in their country. But once these foreigners are in Denmark, that’s it – in the minds of Danes, they remain foreigners, and thus they can’t assimilate to society in the same manner. Ask a hundred foreigners this question: “How many Danes have invited you into their homes since you’ve been here?” It’ll be a very low number. Thus, many foreigners remain in their own international communities while living in Denmark. So there is a Danish fence as well – it’s just not at the border. I fear that it is what the Danes call a ‘bear favour’.

What is the reason for some of the greatest misunderstandings in your view?

I think it’s a lack of historical context for most people. Once you sit down and explain to someone, for example, how communism has affected Hungary and how a given initiative today could be an attempt to fight those repercussions, they will usually at least begin to understand.