Vinland, oh mythical Vinland, where art thou? The most significant contest in North American archaeology has been ongoing for centuries: to find the original site of Vinland, the landing spot of Leif Erikson’s expedition in 1000.

Not L’anse aux Meadow!

National Geographic magazine thought it had found it a few years ago. But despite sophisticated satellite surveillance and hundreds of thousands of dollars, its best effort turned out to be an abandoned farm from the 1930s.

And archaeologists know with certainty that the Canadian Viking site L’anse aux Meadow on the island of Newfoundland is not where Erikson landed. Their work, over the last 40 years, has confirmed that women lived at L’anse aux Meadow and that domestic animals were present as well. That would indicate that the site would have been a subsequent settlement location.

Recent carbon dating research has shown that it existed in the year 1021. Erikson’s voyage of 21 years earlier, when he ‘discovered’ Vinland, was solely to harvest timber for house building in Greenland. The sagas tell us that 30 men accompanied him. No women, no animals.

Many theories abound about the exact site of Vinland, and the most esteemed Icelandic historian even claimed the location would never be found! Magnus Magnusson stated that the Icelandic Sagas are too vague and contrary to decipher an exact geographic location.

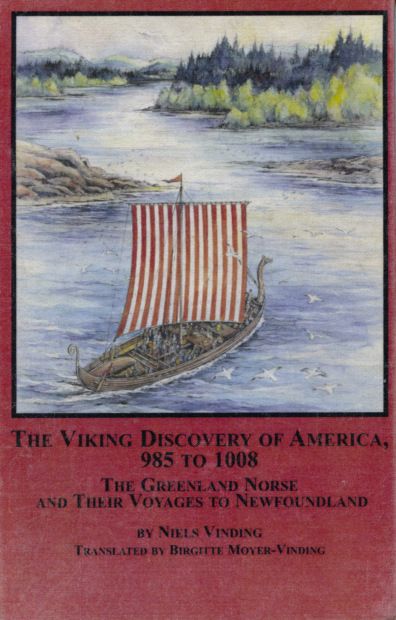

But what if a dedicated Dane has already cracked the case? I believe that the late Niels Vinding of Copenhagen established the location of the Vinland landings in 1997. He wrote a book about it, but he died before fully proving his case.

Stumbled upon a boulder

My story is crazy as I pretty much stumbled into one of the greatest mysteries of the last 1000 years: where is Erikson’s Vinland?

I am a Canadian interested in indigenous rock art. Much of my work is discovering obscure inscriptions written in exotic scripts on hidden rock faces in the wilderness of Canada.

That search led me to the wilds of Newfoundland to see an unusual Iberian inscription near the only known Viking site in Canada. During that exploration in 2011, I was told by the head of archaeology from the local university about a recently discovered inscription boulder in southern Newfoundland with what appeared to be several Viking runic inscriptions.

I travelled to see them and was impressed by their age and the skill needed to carve them into a granite boulder. The lichen covering parts of the script spoke of hundreds of years of exposure.

A Canadian Viking runic expert who I consulted claimed to be able to read what was a vague statement about ice and cold and being stuck there for the winter. But the owner of the boulder claimed her daughter had carved them when she was a teenager. I doubted the wisdom of a teenager to know Viking runics and then the tenacity to complete such a skilled job.

I shared the images with Lisbeth Imer from the Danish National Museum, and she claimed they were recent. I later discovered that the boulder had been known about for at least a hundred years prior, but at some point was removed from its original location. I was intrigued by the discrepancies of the stories and started a broader search.

On the same trail

I was stunned to discover that Niels Vinding, the Dane at the heart of this story, had come to this same harbour to search for Vinland. He was looking for discarded ballast stones after learning the location from a Canadian writer who had theorised that this was the most logical place for Erikson to have landed. In his book ‘West Viking’, the well-known Canadian author Farley Mowat observed that discarded ballast stones would be the clue to finding the original Vinland.

Thus, Vinding travelled to Canada and spent the summers of 1997 and 1998 searching for unique and suspicious stones at Bellevue Beach on Trinity Bay. And he found some! The local university’s geology department identified the stones as columnar basalt but of unknown origin – definitely not Canadian. No-one seemed to care to push this mystery any further. In 1998, Niels published his discoveries in a book, ‘The Viking Discovery of America, 985 to 1008: The Greenland Norse And Their Voyages to Newfoundland’, shortly before dying of cancer. The book was not translated into English until 2006.

Wary of vested interests

Now I love a good mystery, and this all seemed very logical. Viking runes – check; ballast stone – check; a well thought-out theory – check; an appropriate beach location – check.

But why wasn’t anyone in Newfoundland interested in pursuing this fascinating story? I finally realised that the government has spent millions of dollars on building a replica Viking longhouse and interpretative centre at L’anse aux Meadow and was not keen on having some amateur change the paradigm. Yes, for sure, L’anse aux Meadow is still an excellent Viking site but not what it was initially claimed to be!

Since I am not an academic and had no reputation to protect, I jumped into this story and have worked on it for eleven years from all possible angles. All of the site specifics that Erikson described exist at Bellevue Beach. It is a beautiful fjord-type setting with a big sandy landing beach – more beautiful than the barren rocky shore of the presently known Viking site. Like a lot of archaeological finds, it is hiding in plain sight! It is in a public park now overgrown with trees and scrubby underbrush.

Sourcing the stone

In 2014, I travelled to the harbour for a second time and convinced the owner of one of the ballast stones found by Vinding to let me have a sample for analysis.

He obliged, and I was able to have it analysed by a high-tech lab through a process called ‘Spectrographic Analysis’. Using nuclear furnaces that burn the stone at impossible temperatures, the gases that are driven off are analysed and recorded. The easy explanation is that it is like doing the DNA of a crime scene.

The problem is that I then had to find the stone’s source location to get a sample for comparison. Knowing that Erikson had initially come from Iceland, I figured that the columnar basalt ballast stones were from there. After all, the main cathedral in Reykjavik is built to look like columnar basalt. I obtained a sample from Breidafjordur Bay, where Erikson lived before moving to Greenland, but to the naked eye, the internal colour was obviously different.

After struggling to make that theory work, I switched my focus to Greenland. It would make sense since that is where Erikson was living with his father Eric the Red on what was called Ericksfjord (now Tunulliarfik Fjord). He sailed from there in a knarr that he had bought from Bjarni Herjolfsson, another Icelander. Herjolfsson was the first to see a mysterious wooded island west of Greenland after being blown there during a major storm.

Mining the truth

My research started by scanning tourist photos from Greenland on Google Images. I spotted similar suspicious square boulders in a Viking church ruin called the Hvalsey Church that dates to 1000 AD.

Widening the visual search, I found a replica Viking stone and turf house at a museum in the village of Narsaq. That village sits at the end of the Tunulliarfik Fjord. I contacted the museum and was able to talk to the curator, another Dane by the name of Jesper Enevoldsen, who was quite supportive of my research. He sent me a photo of what appears to be a quarry of columnar basalt from his village. The story was a grand theory, but I still did not have conclusive evidence that the archaeology community would accept.

Having found a promising location for the rock source, I started drilling down through the internet concerning basalt in that area. I eventually found research carried out by the University of Edinburgh: some spectrographic analysis for mining purposes on the fjord. By comparing the two data sets, I was able to see that the list of mineral elements absolutely matched. What a relief!

Behold the holy ballast

It now seems so easy to understand that Erikson would have ballasted his boat in his home fjord. The boat would have been very light as they sailed from Greenland to Newfoundland with no cargo, so the addition of extra weight was necessary.

The essential thing to know is that the square boulders of about three feet long, 12 inches high, and 18 inches wide were apparently then used as foundation blocks in the temporary turf houses they built in Vinland – turf houses in Iceland have a foundation of similar columnar basalt blocks crucial for moisture drainage.

As a matter of interest, one of the ballast blocks can still be seen in situ in what appears to be a turf house foundation in Newfoundland. Specialists at the Roskilde Ship Museum who I contacted were highly sceptical of this kind of sizeable square ballast. Other mariners have told me that you use whatever is available at the location you are departing from. The matching of the rocks answers that argument.

False seeds, or perhaps berries

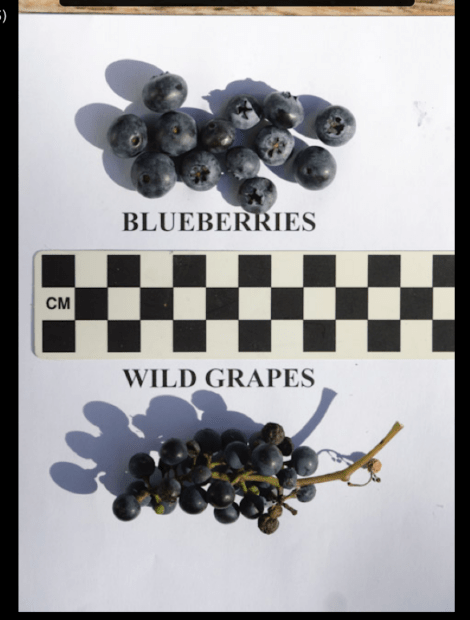

Another vital part of this ‘saga’ that needs to be considered is the name Vinland – the land of grapes. Historians for centuries have argued that Vinland can’t be in Newfoundland because grapes don’t grow there and never did.

No-one, it seemed, has ever questioned the veracity of Erikson’s statement that he found grapes! Was it a deliberate attempt to promote his discovery of the wonderful island, or a genuine mistake. The Greenlanders had never seen grapes growing, so you can understand the mistake.

And of course, the similarity of wild grapes to blueberries is easy to see. They are still making outstanding blueberry wine in Newfoundland.

On the verge of greatness

Now that I have absolute scientific proof of the stones having come from Greenland, a full-on archaeological survey will most likely show a turf house ruin that still exists on Bellevue Beach. Once that is established, connecting it to Erikson will be easy, and we can say we have indeed found Vinland!

As a contemporary footnote to this discovery, the spectrographic analysis of the ballast stone indicates that they are full of rare earth Minerals. Thus my curiosity about some contentious Viking runic inscriptions has bridged a historical 1000-year-old myth with contemporary geo-political ambitions, as China has claims on the homeland of Erick the Red and Leif Erikson for mining purposes.

I only wish that Niels Vinding had lived long enough to see his work proven.