On September 11, Denmark’s neighbours across the Øresund headed to the polls. A right-wing bloc has now emerged with a majority in the Swedish Parliament, stripping PM Magdalena Andersson and her social democrats of their position at the head of government.

However, it was the days and weeks prior to the election that revealed the full extent of Sweden’s shift to the right. During this time, Andersson and her party proved more willing than ever to adopt the type of anti-immigration measures that have made their opponents popular, including one distinctly Danish policy that has earned Denmark the ire of activists, NGOs and the UN: the ghetto plan.

The years-old ghetto plan, which was rebranded as Denmark’s “parallel society” policy in 2021, imposes special housing, education and policing measures in residential areas that the state has designated on the basis of not only their socioeconomic status but also on their racial and ethnic composition.

“Holes have been made in the map of Denmark,” contends the government’s ‘One Denmark without Parallel Societies’ report. “Here, an excessive proportion of citizens do not take sufficient responsibility. They do not actively participate in the Danish language, society and labour market. We have a group of citizens who do not embrace Danish norms and values.”

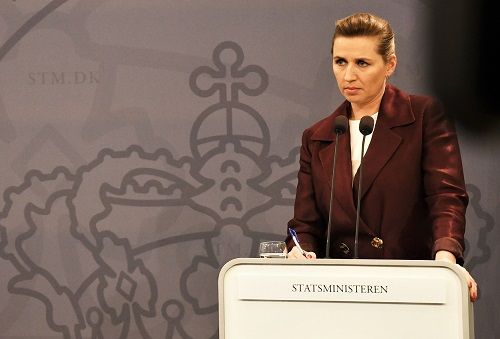

That irresponsible, values-lacking group of citizens, according to the plan, is Denmark’s immigrant population – particularly those of “non-Western origin”. Due largely to this distinction, Denmark’s ghetto plan has been subject to widespread international condemnation, with critics calling it racist and discriminatory. Nevertheless, Mette Frederiksen and her Socialdemokratiet party have continued to support the policy, which was first implemented and then overhauled during the non-consecutive terms of former PM Lars Løkke Rasmussen, the former leader of the right-wing Venstre party.

Socialdemokratiet’s Swedish counterparts then duly followed suit with their pre-election campaign push, which included language and policy proposals eerily reminiscent of the Danish policy. The party’s election manifesto, for example, outlined policies to prevent new arrivals from settling in areas where large concentrations of non-Swedish ethnicities already reside.

And in early August, the Swedish PM announced new punishments for gang-related offences, including lengthier prison sentences, linking the problems explicitly to immigration. “Too much migration and too little integration has led to parallel societies where criminal gangs could take root and grow,” explained the Swedish PM regarding the new punishments.

Finally, the Swedish integration and migration minister, Anders Ygeman, proposed a 50 percent limit on concentrations of people with “non-Nordic” backgrounds in “troubled areas”.

Tough on immigration

It’s a tired tale. With an election approaching, politicians rush to rile voters to their side. Inevitably, it’s another draw from the well that never seems to run dry: the threat of the other. Whether on the basis of some political calculus or deeply-held values, they bet on those voters who believe that immigrants and outsiders are to blame for their country’s woes.

In France’s last election, right-winger Marine Le Pen predictably drew deeply from that well, making immigration a centerpiece of her campaign. Despite gaining ground in her third attempt at the presidency, the approach failed to grant her victory over incumbent Emmanuel Macron – the candidate of the long mythicised political centre whose campaign promises also included a tougher stance against immigration.

In the time since the last US election, Republicans have perpetually shone a light on the crisis at the border as evidence of President Joe Biden’s lack of leadership, hoping such sentiments will keep the political pendulum swinging in states like Arizona, Georgia and Wisconsin when the Oval Office is up for grabs again in 2024.

The underlying fear that critics say is exploited by tough-on-immigration politicians – and that which makes it such a potent political talking point – is at least in part exemplified by such baseless notions as the ‘Great Replacement’, which has under the guise of an academic theory become a buzzword in both France and the US.

It is Denmark however – the progressive beacon that American leftists acclaim to prove socialism isn’t a bad word and French expats move to for better work-life balance – that has most explicitly put forward a policy aimed at preventing the outcome forewarned by conspiracy theories such as the Great Replacement: the rise of a majority-minority state and the subsequent collapse of national values. That explicit goal of the parallel society policy, according to a 2021 government statement, is to ensure that residents with non-Western backgrounds amount to a maximum of 30 percent in all residential areas in Denmark by 2030.

Denmark’s ghettos

‘Ghettolisten’, the government-curated list of Danish ‘ghettos’, has been published every year since 2010. In 2018, when the term parallel society replaced ghetto as the official designation for these areas, a majority non-Western population became the only mandatory criterium for inclusion on the list, along with meeting at least two of four thresholds in the categories of low income, high crime, high unemployment and low levels of education. As of 2021, there are three categories of residential areas in addition to parallel societies: ‘prevention areas’, ‘vulnerable housing areas’ and ‘transformation areas’.

Danmarks Statistik, an agency under the auspices of the Ministry for Economic and Interior Affairs, defines non-Western as any country outside the EU, with the exceptions of Andorra, Australia, Canada, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Monaco, New Zealand, Norway, San Marino, Switzerland, the UK, the USA, and the Vatican State.

According to critics, the effect is that non-Western disproportionately means non-white. And because the non-Western definition includes both recent immigrants and their first and second-generation descendants, even a person born in Denmark and raised speaking Danish will be considered non-Western if they have recent ancestry in a country not included on the Danmarks Statistik list.

Garbi Schmidt, a migration researcher at Roskilde University, says that the notion of the ghetto has always been tied to race, at least conceptually. In Danish politics, however, Schmidt says that the word has, until recently, had more to do with socioeconomic factors.

“If you look through the 60s, 70s, 80s, and a good part of the 90s, when there’s discussion of the ghettos, it relates to the question of social class,” contended Schmidt.

Since the early 2000s, however, when Denmark first unveiled its national strategy against ghettoisation, this has changed. In its 2004 action plan, for example, the government detailed goals such as achieving a more balanced composition of residents and reducing the concentration of ethnic minorities, as well as immigrants and their descendants, in “ghetto areas” .

Today, furthered Schmidt: “It’s quite obvious that what the plan sees as the problem is immigration and integration.”

Myth or reality?

Unlike Schmidt, Davide Secchi’s research at the University of Southern Denmark doesn’t typically focus on issues such as immigration and race, but rather organisational behaviour and decision-making. Secchi deals in numbers, computational models and, above all else, evidence. After reading about Denmark’s parallel society in policy in 2018, however, he couldn’t help but investigate.

“I was shocked by the claims that were being made, mostly without a shred of evidence,” said Secchi. “There’s nothing called parallel societies in the academic world. There’s no literature on it.”

Secchi asked simple a question about the parallel societies the government was telling him existed in Denmark. Using an approach known as agent-based modeling, an advanced computational method for simulating the actions and interactions of autonomous agents in complex systems, he sought to assess the veracity of the theory of parallel societies. Was it likely, or even possible, for such a social structure to emerge?

“The answer was no,” said Secchi. “You can’t. It’s very unlikely that a high number of people with a similar set of non-Western values would basically aggregate in a specific area in a city.”

“There’s not a one-to-one type of correspondence that if you have a low income, and if you are an immigrant, then you also have values that are not compatible with Denmark. That’s not holding up.”

Secchi planned to continue his research on the matter, but after having two proposals rejected by the Danish Research Council, he lacked the funding and left the question behind.

“I hope that at some point it will be discussed again by politicians with greater orientation towards scientific evidence or scientific methodology,” said Secchi. “I’m not saying that they should be using agent-based modeling, but it certainly deserves more serious interest.”

Speaking of the current policy, he concluded: “It’s not based on evidence, and that’s the most dangerous part.”

Being ‘non-Western’

Amandeep Midha has been living in Denmark for nearly a decade. He is, by the government’s definition, non-Western. An accomplished engineer and industry standout, it is being ‘non-Western’ that to a great extent has shaped his experience in the country.

Last year, Midha scrapped plans to move from Copenhagen to Gladsaxe over concerns that his soon-to-be neighbourhood would end up on the government’s ghettolisten. According to the most recently published list, no community in that municipality has met the criteria, but two have met the requirements to be considered prevention areas – where immigrants and descendants of non-Western origin exceed 30 percent of the local population.

Prevention areas emerged as a result of 2021 legislation passed by a broad majority in Parliament. To keep prevention areas from becoming parallel societies, the legislation introduced special rental rules in the areas and opened the door for “strategic demolition”.

Midha, by moving to one of these prevention areas, would have brought the percentage of non-Western residents ever so slightly closer to 50. And with the percentage already exceeding 30 – the maximum allowed by the 2030 target – he doubted he’d be able to stay for long.

So, Midha moved to nearby Rødovre – a neighborhood not on any of the government’s lists. Here, still, being ‘non-Western’ has brought its own challenges. He recalls a party held at his home in Rødovre shortly after moving in, when a Danish friend of a friend confronted him with a seemingly innocuous question: “How come you live here? Are you Danish?”

For Midha, the question underpinned the kind of sentiment that in some ways explains the existence of the parallel society policy.

“You are not white enough to come and mingle and live in this neighbourhood, and don’t you dare go to another brown neighbourhood because you’ll be here to destroy our society,” he said.

“The entire understanding of immigrant is based on a stereotype of a Middle Eastern patriarchal, brutal, half-terrorist Arab.”

Midha, thankful for the opportunities he’s found in Denmark, was born in India, not the Middle East. Still, while unable to escape the stigma and stereotype of being non-Western in Denmark, he has expressed even greater hope for those who have been more directly affected by the parallel society policy.

This may include those who have lived in one of Denmark’s longest standing ghettos, Mjølnerparken. The infamous housing estate in Copenhagen, of which around 80 percent of residents are classified as non-Western, has been subject to some of the most aggressive efforts by the government to eradicate so-called parallel societies from the country. Proposed measures have included the relocation of entire blocks of residents and the conversion of former public housing into private and co-operative housing.

“Imagine the plight of those people,” said Midha. “The next generation will grow up thinking they were kicked out of a neighbourhood because of their skin colour.”