Åle, a sleepy hamlet in rural Jutland will, on 4 May – Denmark’s Liberation Day, commemorate 80 years since it woke to the smouldering wreckage of a shot-down Allied Lancaster Bomber, five dead Australian and British airmen and two survivors.

When Nazi officers stormed Horsens Hospital to take an Australian airman prisoner of war, a young Danish nurse rushed to put flowers in his arms while her terrified colleagues hid.

Magda Jørgensen, now nearing 103 years old, lives in a care home in the old hospital building where she started her nursing career during the Second World War.

It was here that 22-year-old Ted Suffren received initial medical treatment after a large bit of flak from the plane explosion penetrated his back and pierced his bladder.

A brave Danish doctor refused to hand him over to the Germans for about three days, she said.

‘‘He was a sweet young man, around the same age as me,’’ Mrs. Jørgensen, told The Copenhagen Post.

She couldn’t speak English and he couldn’t speak Danish, but she desperately wanted to communicate with him.

‘‘As they took him away, I grabbed a bouquet of flowers and gave them to him on the stretcher,’’ she said.

‘‘It was a token of appreciation for what he did. I wanted him to know I sympathised with his fate.’’

Suffren had been navigating Lancaster Bomber ME 663 back to England after an overnight mission laying mines at Danzig Bay – the Baltic coast of German-occupied Poland, when a German fighter attacked at 23,000 feet.

That plane was one of nine out of 12 Lancaster aircraft shot down over Denmark on April 9 and 10, 1944.

Australian pilot Peter Crosby, 20, pulled an evasive manoeuvre, diving to 18,000 feet.

He ordered the crew to bale but the aircraft flipped over, plummeting to 6000 feet before Crosby could level it out.

The plane burned from the wings and flames licked the fuselage before sixteen tonnes of wreckage was strewn across farmland and forest near the village of Åle.

Crosby, a surf lifesaver, was dead at the controls along with his fellow Australians – bomb aimer Clive Billett, 25, air gunner Laurence Robb, 33 and wireless operator Leslie Chapman, 20 as well as British engineer Milton Bender, 20. They are all buried at the Danish war cemetery at Esbjerg.

Suffren became trapped trying to help Bender who may have died in his arms.

As the plane was spinning to the ground, Suffren was hurled out and spent the next four hours lying in agony.

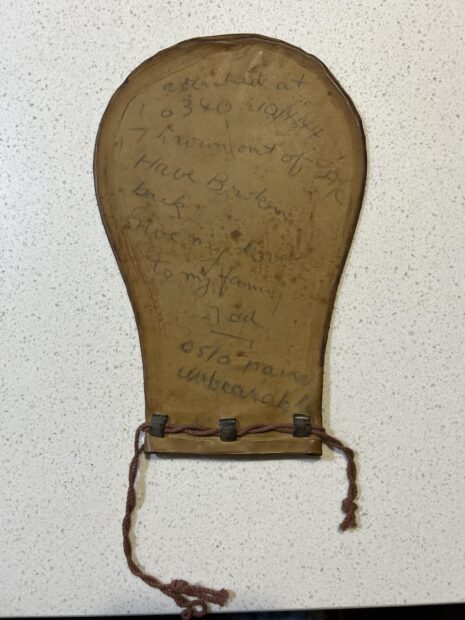

The bank clerk and rowing champion managed to scrawl a farewell message to his family on his water pouch.

‘‘Attacked at 0340 on 10-04-44. Thrown out of aircraft. Have broken back. Give my love to my family. Ted. 0510 Pain unbearable.’’

Police at the crash site initially thought Suffren was dead too, but then saw him move underneath his parachute and called an ambulance.

Danish news photographer Gregers Hansen found Suffren’s pouch and hid it from the Germans.

For 50 years, it sat forgotten in a desk drawer before his journalist son Lars managed to reunite it with Suffren’s sister Roma Pearson in Ballarat via Australia’s Embassy in Copenhagen.

It’s now a treasured family heirloom, Suffren’s nephew David Pearson told The Copenhagen Post.

‘‘One of the stories I remember Mum saying was that her brother didn’t have to go on this last mission. He had already done his 30-something missions. He did it to stay with the crew so they could all finish up on the same day,’’ he said.

Suffren died on February 16, 1945, in a German military hospital and is buried at a war cemetery near Munich.

‘‘Had he lived he undoubtedly would have been paralysed from the hips down and bedridden for life. The German doctors and nurses fought hard for him… they did as much for him as they would have done for one of their own lads,’’ fellow prisoner of war British airman Ronald Chapman wrote in a letter to the Suffren family.

‘‘Your brother was a fine chap and a grand example of the best of Australian manhood.’’

‘‘Our Danish grandmother’’

Rear gunner Stanley Hodge, 21, from Bundaberg, Australia, survived the parachute landing and hid in the forest ‘‘like a bloody mongrel dog’’ for several days until a ‘‘little, whippersnapper of a kid’’ found him and took him to the Boring schoolhouse.

An English-speaking school teacher named Emilie Henriksen gave him food and patched him up but Hodge worried that his presence would place her in danger with the Germans.

He hit the road and intended to try to escape to Sweden, but the Germans apprehended him at a local inn.

He became a prisoner of war and marched between camps across Germany and Poland including Stalag Luft III, which featured in the film ‘The Great Escape’.

‘‘He used to tell us he was so cold that they had to pee on their feet to stop the chilblains. Frostbite. That was the only thing that saved a lot of their feet,’’ his daughter Janelle Clark told The Copenhagen Post.

When the war ended, Mrs. Henriksen tracked down Hodge who had incidentally married the daughter of a Danish migrant to Australia.

‘‘[Mrs Henriksen] sent a letter to the BBC in London and asked them if they could tell her if [Hodge] had survived… when she found out he was alive, Mum and Dad got a letter from her. They wrote to each other until she passed away,’’ Mrs. Clark said.

Mrs. Henriksen also wrote to the other airmen’s families and hosted their visits to Denmark.

‘‘She was like a train station for people,’’ said Danish historian Kristian Zouaoui, who grew up near the crash site and is the present guardian of the airmen’s story.

He inherited Mrs. Henriksen’s photo albums and said among the Australian visitors were Crosby’s fiancée and parents, Suffren’s brother John and Stanley Hodge’s wife Lorna and his daughter Janelle Clark.

A 1950 Australian newspaper report about the airmen, described Mrs. Henriksen as a woman with a beaming face ‘‘who you wanted to hug on the spot’’.

‘‘When we were growing up, she was referred to as our Danish grandmother,’’ Mr. Pearson said.

‘‘We didn’t have one. She was a good substitute.’’

‘‘Mum wrote back to Mrs. Henriksen at least three or five times a year. And Mrs. Henriksen would send her… cross-stitches with our names. Mum once sent her pressed flowers.’’

Mrs. Henriksen’s efforts to help Hodge and her correspondence with the airmen’s families saw her selected as a Danish representative at the funeral of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1965.

A cross stitch embroidery she made, with the names of 47 allied airmen who lost their lives in air crashes near Horsens, hung in the St. Clement Danes church in London.

Ole Kraul from Horsens continued writing to the families after Mrs. Henriksen’s death and he visited them on a tour of Australia in 1978.

Mr. Kraul also helped reunite the wristwatch Chapman’s parents had given him for his 17th birthday. It had passed through two generations of Danes before it was returned to his sister Norma Smyth, 50 years later in Ararat, Australia.

Eighty years on, correspondence continues; Mr. Zouaoui is in email contact with some of the Australian descendants of the airmen and Mrs. Clarke recently shared pictures of her father’s log book with him.

Mr. Zouaoui’s home is like a World War II Museum – he has parts of the wreckage, Crosby’s compass, photos of the aircrew, and Suffren’s star map hanging on the wall.

Standing by the memorial stone erected in 1947, Mr. Zouaoui, a father of two teenagers, says it’s hard to fathom the resilience, courage and daring of the ‘‘greatest generation’’.

‘‘Would [my kids] be able to fly a Lancaster with six of their mates? Not sure if they’d be up to the task.’’

‘‘The people back then just endured. They were hard.’’

Across the world, on a South Australian beach, Gareth Gray from the Seacliff Surf Lifesaving Club also contemplates the fearlessness of Crosby and his crew, as members paddled out on boards and boats to lay a wreath and sprigs of rosemary on the water for the 80th anniversary April 10.

‘‘Peter was called upon to do this job that cannot be imagined,’’ he said.

‘‘I see in the kids at the club the exact same traits today that made Peter do these amazing things. Daring and skill, a great sense of mateship.’’

But the late Stanley Hodge, who died in 2007 at age 87, always shrugged off any bravado.

‘‘I hated the bloody lot. I was frightened of every one of them… If anybody wasn’t frightened, he was a liar, or he was mad,’’ Hodge told the Australian War Memorial’s oral history project in 1987 when asked about his operations.

On May 4 at 13.00, there will be a special ceremony for the airmen of Lancaster ME663 at the memorial stone at Åle.

More than 1100 Allied airmen from 300 crashed aircraft are buried in Denmark.

Lisa Martin is an Australian freelance journalist in Copenhagen.

www.lisapmartin.com