In the last decade alone, Denmark has experienced several instances of devastating flooding, most recently in the winter of 2023, where several areas of the country had to be evacuated due to high sea levels and the total cost of damages was estimated to run up to 1.2 billion Danish kroner. Furthermore, experts are expecting the danger from storm surges, “monster rain,” and rising groundwater levels to grow significantly in the coming decades.

So what can Copenhagen do to combat the dangers that the surrounding waters pose to the city, and is there a risk of large portions of the city ending up underwater? While there are currently several plans in the works, the road leading to absolute protection of the city is still murky—if even possible.

Not a matter of if, but when

According to a report released in November 2024 by DTU in collaboration with the CIP fund, the number of people in Denmark who will be affected by storm surges will grow five times higher in the next century compared to the current number. What’s more, 500,000 houses and buildings are at risk of being flooded in the next 50 years.

While sea levels themselves will rise by approximately 54 to 74 cm, according to GEUS (The National Geological Surveys of Denmark and Greenland), it is especially future storm surges that are concerning for Copenhagen politicians, as the water levels in Øresund could rise by over 4 meters in certain powerful cases, effectively threatening large parts of the city.

The possibility of these powerful storm surges threatens a large part of Denmark’s population. According to a report released in September last year by the Danish Coastal Directorate, 51 of Denmark’s 98 municipalities are now in danger of being flooded to some degree in the case of storm surges, including Copenhagen and its surrounding municipalities.

The cost of damages from these occurrences will also rise if no action is taken. The DTU report states that flood-related damages could reach 72 billion Danish kroner if no protective measures are implemented within the next decade. This figure could rise to 158 billion within 25 years and 262 billion within 50 years.

Many architects and city planners are aware of the situation, and various strategies—from large-scale urban planning to micro-level solutions like water-absorbing pavement tiles—have been developed in recent years. Several strategies have already been implemented in Copenhagen to address the issue. One example is the numerous “Local Diversion of Rainwater” strategies, which involve designing city spaces specifically to divert rainwater away from streets and into underground reservoirs. These have been in place since the 2011 cloudburst that flooded many parts of the city.

Examples include Enghave Parken in Vesterbro, which was renovated in the late 2010s to withstand large amounts of water, as well as “the climate district” in Østerbro, where every renovation is carried out with climate resilience in mind.

Protect what can be protected

While the city has already implemented these local strategies, several large projects are in development to protect Copenhagen in the future. One such project is the much-debated Lynetteholm, a proposed artificial island between Nordhavn and Refshaleøen designed to shield the city from storm surges.

Architectural firms are also exploring more innovative ideas, such as Schønherr’s vision of a Copenhagen consisting of islands to help manage rising water levels.

However, many experts warn that not everything can be saved and that some areas will likely be lost if water levels rise. This perspective is beginning to influence local politicians as well.

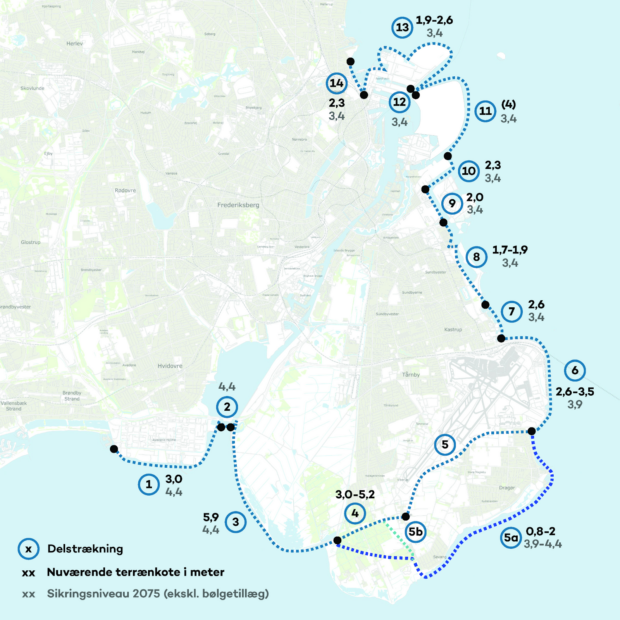

One example is a new municipal plan that has just completed its first research phase. It proposes building a “wristband” of dykes around the island of Amager to protect the greater Copenhagen area. According to the plan, these dykes would reach several meters in height and serve as the last line of defense against severe storm surges that could otherwise flood much of Amager, Christianshavn, and the inner city.

However, some proposed versions of the project do not include large areas in the southern part of Amager, including the town of Dragør. This means that if a rare but powerful storm surge occurs, residents in these areas may be left unprotected.

As a result of this announcement, some Dragør residents have reported difficulties selling their homes. This version of the plan has been heavily criticized by local citizens, who feel abandoned.

The total cost of the project is estimated at 13 billion Danish kroner. While the financing has not yet been determined, involved mayors have stated that they are looking for a solution based on solidarity between municipalities and their citizens.

The project is expected to take around 40 years to complete—a long time in an era where storm surges may become more frequent and severe.

The final version of the plan to protect the city from storm surges has not yet been confirmed, but as extreme weather events become more common, the countdown to the next major flood in Copenhagen continues.

An exhibition about rising waters and climate change

Currently, at the Danish Architecture Center, the exhibition Water is Coming is on display.

It will be open until March 16, 2025.

“Poles are melting, groundwater is rising, and torrential rain is flooding roads and houses. It’s no longer a question of if, but when the water is coming – and how we adapt.”