Formerly used as command posts, air raid shelters, surveillance stations, radar stations and forts, Copenhagen’s underground bunkers are slowly being transformed into shops, galleries and even nightclubs opening their doors again.

Built to house government leaders, the reigning monarch, mayors, police chiefs and military personnel to ensure Denmark could operate in the event of war, Copenhagen’s secret bunkers, after years of being kept under wraps, are gradually opening their doors to an inquisitive public.

As in most other European capitals, city centre space is at a premium in Copenhagen. It is indicative of this problem that an increasing number of people are willing to consider locating their shops, clubs or galleries in a windowless, subterranean cellar up to five metres below street level. The bunkers are becoming increasingly popular with those seeking cheap, centrally located, albeit unorthodox property.

Mostly Cold War

Most of the country’s military bunkers were constructed 60 years ago. With the Cold War at its height, Denmark was a front-line state, counting both Poland and East Germany among its near-neighbours. Worried that Copenhagen might be a prime target, the government took the decision to build some 2,000 bunkers, of which 1,000 were sited in Copenhagen.

Located mostly in parks and other public areas, the vast majority of Copenhagen’s underground shelters are empty, damp, poorly maintained and, on the whole, uninhabitable.

Popular conversions

Many are situated in what are now some of the most desirable areas of the city. Responsible for overseeing the bunkers, Copenhagen Municipality is turning these former white elephants into money-spinning enterprises.

Those deemed to be in good enough condition are being rented out as shops, art spaces or clubs, and the municipality is also willing to rent them out for a weekend or just a single night. At Fælledparken some bands have been allowed to use the bunkers as rehearsal rooms, and this was a huge success.

Cavernous under Christiansborg

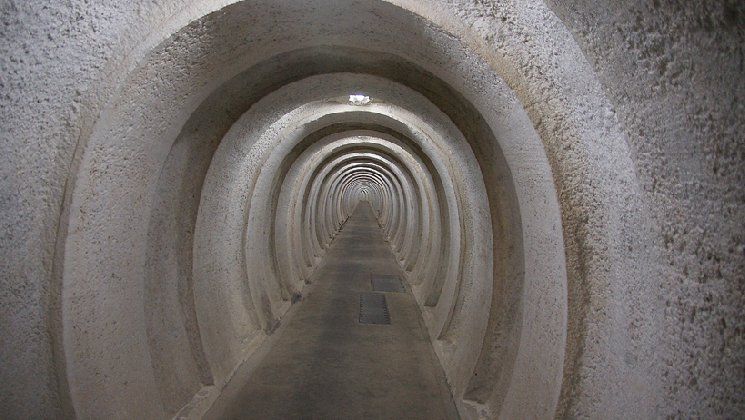

Some have not been fully opened yet – take for example the network of corridors under Christiansborg, which were reportedly built as escape routes for politicians and royals to use during the war.

The tunnels are no longer used, but located pretty much under the prime minister’s office and the King’s Gate, close to Christiansborg Palace Church, there is a command centre where the government could lead the country.

The secret room dates back to the 1930s – not when the concern was war but rather a coup d’etat orchestrated by the Nazis or Communists.

Huge hospital in a hole

Similarly, under the old municipal hospital on Østre Farimagsgade is situated a 600 sqm emergency hospital built during the Cold War to be used in the event of a nuclear attack.

Back when it was built, it had the capacity to operate on 30 people at the same time. Inside the walls are painted a pastel green – designed to give off a luminescence to help people to see. Other walls are coloured a darker green because of its calming effect.

Today the hospital is obsolete, but it is sometimes used as a warehouse and sometimes for cultural events such as opera.

Subterranean to the skies

One of the largest bunkers in the Copenhagen area was built in Rødovre in 1954 as a command centre for the Danish Air Force.

In the middle of the 1,300 sqm bunker is an operating room connected to radar stations that monitored the airspace and cannon and missile batteries around Copenhagen. The bunker was manned around the clock, ready for battle.

It was only in 2004 that the last employees left the bunker, and in 2012 it was opened to the public as part of an experience centre in Vestvolden.

Potholes in the park

One of the most popular bunkers is situated in the middle of Copenhagen’s Faelledparken and, until recently, anyone could have rented it. The spacious underground cavern, with no neighbours to complain about the noise, was a huge favourite with the techno party crowd. It is still possible however to rent other bunkers for whatever reason through Hovedstadens Beredskab.

Close to Copenhagen Zoo, an innocuous looking entrance built into the lawns of Søndermarken public park houses a trendy art gallery and exhibition space, called Cisternerne. The dark, cold and moist underground world beneath was formerly used as a large water reservoir containing 16 million litres of drinking water, which was dug out in 1856.

Other Copenhagen bunkers include one located by Dronning Louise’s Bridge, which for a while housed the specialist occult bookshop Osculum Infame, and another on Sankt Hans Torv, where a second-hand clothes shop opened, retaining the original name, Bunker 301, although it has since then, like the Cold War, closed forever.

Bunkered in by the Brits

Some of the bunkers have a story to tell that goes way beyond the 1950s. Although most structures date from that era, some were built in the early 1800s after the Danish capital suffered a firebombing in 1807.

During the Napoleonic wars, the British subjected the city to a bombardment that destroyed hundreds of buildings and injured many thousands of people, with at least 200 dead. Despite Denmark’s declared neutrality, the British rained shells and rockets on the city’s terrified inhabitants. Houses, apartments and entire buildings were ripped apart and reduced to rubble.

After the blitz was over, the civic authorities realised that many deaths could have been avoided if the citizens had somewhere to shelter. A project was envisaged to build vast underground halls to allow every Copenhagener a place of safety underground. Although these plans never came to fruition, some evidence of the ambitious scheme remains.

Examples of early shelters can still be seen in inner city squares such as Israel Plads, Kongens Nytorv, and Christianshavn Torv, where construction workers recently discovered what is thought to be an early shelter 10 metres below the surface.

Denmark’s largest

To find Denmark’s largest bunker, you need to venture outside the capital region to the west coast of Jutland. Named after a German battleship, the Tirpitz Bunker was originally supposed to defend the seaport of Esbjerg but never saw military action, and Nazi soldiers abandoned it in 1945 when the German surrendered.

For decades, it sat empty – a dark reminder of Nazi-occupied Denmark. However, in 2017, the BIG architecture firm expanded and redesigned the bunker to house a WWII museum. Dubbed as ‘a sanctuary in the sand’, it delicately cuts into the neighbouring dunes, enabling plenty of daylight to shine into the underground space.

Despite being tucked away, the museum stretches across a generous 2,800 sqm floor plan, which includes four large exhibition spaces within and beyond the imposing cast-concrete bunker. And at the heart of the museum a central courtyard with six metre-high glass panels surrounds the space.

Warsaw Pact police

Another Jutland bunker in use can be found close to the royal park of Marselisborg outside Aarhus. Currently under the jurisdiction of the Maritime Intelligence Service, the structure was constructed by the Germans during WWII.

Notable for its metre-thick walls, it was taken over by the intelligence service after the war as a place to chart the sea traffic – particularly Warsaw Pact ships and submarines – in the Baltic.

Today, with no enemy to keep tabs on, there is an air of neglect about the place. Most of the military staff have departed, and those who remain are concerned mostly with the monitoring of civil vessels. The formerly top-secret establishment is a favourite of visiting schools parties, and its very existence is currently under review.

Carved into a cliff

Monitoring Warsaw Pact traffic was also the chief concern of a bunker carved into the cliffs at Stevns Klint just south of Copenhagen.

Built between 1950 and 1953, it included a 1.7km long corridor with rooms for hundreds of people, as well as a hospital and a chapel.

Its task was to control the Øresund. Together with the fort at Langeland, its purpose was to prevent the Warsaw Pact’s large fleet in the Baltic Sea from gaining access to the world’s oceans – by among other things stopping them from de-mining the minefields.

Fittingly today, it is now a Cold War Museum.

Not so lucky

Other bunkers have not been so lucky and been long since abandoned.

Some 60 metres beneath Rold Forest in Regan Vest near Aarhus, a bunker was built between 1963 and 1968 in case the government needed a Jutland base to manage a civilian crisis in the event of a military attack on Denmark.

Built in a lime pit blown into a hill, the bunker consists of 150 rooms and space for 350 people. With almost 2 km of walkways, tunnels and shafts, the bunker is huge. The last employees left here in 2003, and today there is no access to the bunker at all.