“Denmark among best EU countries for foreign languages” said the subject line of an email I received last month. Inside, it went on: “Only 4.2 percent of people in Denmark can’t speak another language; an impressive 95.8 percent CAN.” Perfect breaking news for CPH POST, I thought, or so it would’ve been had I received the mail in 2016 – when Eurostat compiled the data. It was updated in 2019, true, but that might have just been the adding of a missing ‘e’ to ‘Grece’ (a change to the metadata), since the actual numbers are still seemingly about four years old.

The email came from the Knowledge Academy, which has given a fresh coating and a new life to this EU survey – perhaps in order to raise awareness about the lack of foreign language skills in the UK? (We’ll return to the Brits later on.) In any case, I took this blast from the past and used it as a springboard to examine Denmark’s current relationship with foreign languages.

In my quest, I encountered two experts on language skills in Denmark: Mette Skovgaard Andersen, the head of the Danish National Centre for Foreign Languages (NCFF), and Anne Holmen, the head of the Centre for Internationalisation and Parallel Language Use (CIP) at the University of Copenhagen. And unsurprisingly both of them had some fascinating insights to offer. Their comments are the main ingredients in what follows, so let the feast begin!

Confidence versus reality

The data is part of the Adult Education Survey of Eurostat, the statistical office of the EU. Taking a look at some of the details behind the impressive numbers, 41.2 percent of Danes reported speaking two languages, and 24.6 percent a total of three. Only 29.9 percent speak just one foreign language. The survey focused on people between the ages of 25 and 64, and their language knowledge was self-reported, which means nobody got tested.

“What we can really deduce from this data is that Danes themselves think that they are mightily good at speaking foreign languages. That might not always correspond to what others experience,” said Andersen.

Indeed, 75.6 percent of the respondents either said they are ‘good’ or that they are ‘proficient’ at the foreign language they know best. Only 24.1 percent claimed to be a basic level, which in this survey means to “understand and use the most common everyday expressions”.

This incompatibility between confidence and reality reveals itself, for example, at universities, contends Andersen: “When Danes start and have to read academic texts in English, they actually have a problem fully understanding them. There have been studies conducted about this.”

The bitter truth

The reality today is that Danes are gradually becoming worse at speaking foreign languages. “In the past, we typically studied three languages at high school: Danish, English and another one,” continued Andersen. “This number has fallen substantially: from about 40 percent of high school graduates studying three languages to 4-5 percent. This decline is why our centre was created.”

Holmen’s opinion, meanwhile, is that the survey “might have been a true picture of language skills in 2016, but it’s a picture that resulted from earlier interest in foreign languages, which has been declining over the last 15-20 years. It is a historical picture that’s fading.”

Scandinavian family drama

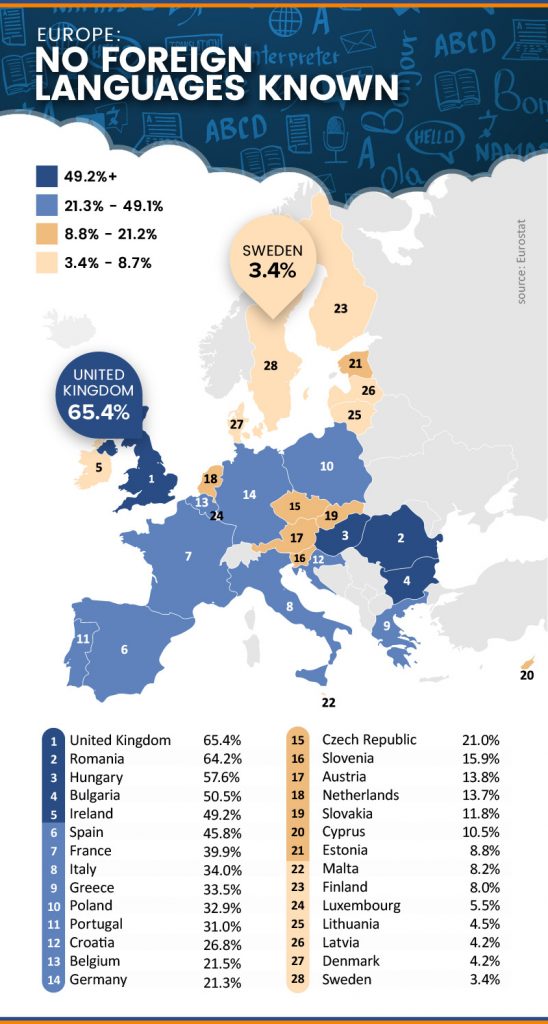

So for self-confidence in 2016, Denmark actually fell short of the gold, continuing a long standing sibling rivalry with Sweden in which their neighbours invariably end up taking first place. Only 3.4 percent of Swedes said they do not speak any other language.

This might be a painful blow to relive for Denmark – partly because they lost the Thorsteinson War to Sweden in 1644, and partly because the Swedes has also beaten them in Education First’s English proficiency index twice since this EU survey – in 2018 and 19. Denmark took fourth place in the most recent iteration of that ranking, falling behind the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway. In the glory days (2017), DK stood tall at the top of the podium.

A somewhat realistic picture

Both language professionals I spoke to contend that the Danish placement relative to other EU countries (second best) seems like a realistic picture even in 2020.

Andersen backed up this aspect of the data: “Of course we are better than many other countries, at least at English. But this makes good historical sense – we are a much smaller country and it has been necessary for us to learn other languages.”

What did Danes do so well?

What code did Danes crack to get to this relatively good position (even if they are in the process of getting worse at foreign languages)? One explanation I got from Andersen is the early introduction of languages in primary schools, where “we have pushed English down to 1st grade and German to 5th grade”.

Holmen pointed to the Danish school system’s focus on speaking, making students put their knowledge to actual use: “I think that the introduction of communicative teaching, which sets communicative skills as its goal, has done a lot of good – especially regarding English – in making students fluent language users. And I think this rubs off on the other foreign-language subjects as well. We started introducing this to primary schools about 30 years ago.”

And then there is pop-culture, adds Andersen: “Young people are constantly surrounded by English – when they play computer games or watch TV, for instance – and they are being told that English is important. Of course, once they gain some English skills in this way, they naturally begin to gravitate more towards English.”

How you doin’?

Certainly, whenever I discuss Danish language skills with others, I bring up the lack of dubbing: most films, TV series and other shows are aired in their original languages – usually English. Thus, Danes grow up reading Danish subtitles and listening to English, while Germans grow up thinking Matt LeBlanc can actually say: “Na wie geht’s denn so?”

(It must be added, however, that dubbing can occasionally enhance the original contents – watch Steve Martin’s Pink Panther in Hungarian and cry with laughter, and you’ll know what I mean).

Language nepotism

Another explanation might be that when Danes learn another language they usually learn English or German as they are, like Danish, both Germanic. But the same choice would be true in Hungary, for example, even though Hungarian is a Uralic language and in the same family as Finnish and Estonian. Hungary is third worst on the list.

But while Holmen conceded that the Hungarian example made good sense, there are “a very large number of Danish words derived from German. So if a teacher conducts language comparisons, students’ vocabularies suddenly undergo a marked expansion. And this, of course, is something that happens with languages related to our own.”

Why the decline?

Holmen and Andersen both concur that foreign language skills are actually declining in Denmark, and the impact of English has played a major role. “There is an implicit sense that we can get by with English: that it is enough to educate a whole bunch of people to speak English. It has had the effect that English has assumed primacy and pushed other languages to the sidelines. I don’t think this was intentional – it’s just what happened as young people are exposed to a massive amount of English,” contended Andersen.

“Also, we cannot get young people to understand that foreign languages are actually an important skill that one can use in a lot of different ways and contexts. You don’t need to have foreign language skills as your main skillset, but basically all professions would gain from such skills as it would allow people to acquire knowledge from other languages – in all fields.”

Hallo? You there? You’re breaking up

Andersen questions whether the Danish education system could be a more seamless experience, as children finish their elementary schooling aged 16 and start considering their university options at an upper-secondary establishment.

“A big problem is that the different levels of education don’t communicate very well with each other: I’m talking about primary school teachers who graduated from Provisionshøjskolerne, and high school teachers who come from universities. The connection between these two teaching traditions is not optimal,” said Andersen

“The reason is that these teachers are educated very differently. At Provisionshøjskolen, there’s a lot of focus on being a teacher – that’s the highest priority for them. The subject they’re learning is also important, but less so. So they actually don’t get too much language even though they choose to study language. They are first and foremost teachers. At universities, on the other hand, you get a lot of knowledge but not about pedagogy. So there are different attitudes as to the nature of the subjects they teach. Thus, young people come to feel that things don’t really fit together. And I think this demotivates them. They run into situations in which some of what they learned before turns out to be wrong later on, or they are told they are going to learn something and then they end up learning something entirely different.”

How could Denmark turn this around?

One area that could influence some change in the larger scheme of things is high school – the gymnasium upper-secondary schools for students aged 16-19.

Holmen recommends a change in the way subjects are offered to students: “In high school, you have packages of subjects that you choose between. It’s important that foreign language subjects are placed so that they become an attractive option. There was a tendency to place high-level English in a package with social studies. We could work with that: we could put another foreign language there as well. And social studies could collaborate with the language subjects regarding the content of the lessons: students could deal with some interdisciplinary topics.”

So, for example, a social studies assignment about Germany that would require German language skills to be properly completed? “Yes. This might be the way forward since it illuminates the fact that languages can function in many different ways and contexts, granting access to many different types of knowledge.”

Kids and curiosity

Holmen believes one of the causes of the decline occurs when kids are first introduced to the language. She thinks changes need to be made at this stage too: “I think it’s very important to build a strong curiosity for languages early on in primary school. In this process, it’s vital that all languages in the classroom are considered legitimate – particularly all the minority languages. Because if all the students’ languages are legitimate, then all the other languages become interesting.”

“One could work with language awareness, for example – so kids can reflect on language. You could do something like have students learn a certain thing in several different tongues: how do you say ‘Hi’ in all the languages spoken in that classroom or how to sing ‘Mester Jakob’ [‘Frére Jacques’ or ‘Brother John’], which exists in 15 different languages?” continued Holmen.

“There are so many of these easy tasks appropriate for kids aged 6-7 – when they are still quite open and you can spark an interest in them. You shouldn’t plague them with correctness at this point. The teacher doesn’t need to know all the languages her students speak, but she can have a pedagogical approach regarding how to respect them, how to speak about them, and how to include them in comparisons etc. This can be mastered without having to learn 25 different languages. And this applies to everyone: we need to have a way to relate to other languages, even if we don’t speak all of them.”

Losses and gains

To recap once more: yes, Denmark is doing well compared to many other countries, while in reality it’s becoming worse compared to its own history with foreign languages. In that light, it’s worth asking the question: what do people gain from having the ability to speak several tongues or, turning the other side of the same coin, what do they stand to lose if they let such abilities deteriorate?

English: a real holy grail

When it comes to English, according to Education First (the international education company), studies show that good English skills raise the chances of getting a higher salary as well as the level of success in one’s professional life. EF also states that there is a proven link between a country’s English skills and quality of life: including average lifespan, education and GDP. And indeed, the number of English speakers around the world exceeds 2 billion – a large market to have access to.

Military means

But it’s not all about English, of course. Holmen talked about how Denmark profits from contact with the rest of the world in general, be it regarding international organisations, private companies, tourism, journalism or defence: “Indeed, the military also requires a lot of English proficiency as we are a NATO country. But it needs other language skills as well: right now mostly Afghan languages and Arabic, whereas it used to be predominantly Russian.”

Objection votre honneur!

Lawyers also benefit from having good foreign language skills. Holmen highlighted the need for French, for example: “There was a report a few years ago about the need for French in Statsforvaltningen [since replaced by the Agency of Family Law]. We have EU laws and agreements, and French is one of the official languages of the EU. There are some EU courts that operate in French. This means that from a legal standpoint we could profit from knowing some French. It’s not necessary to be able to understand, speak, read and write French – you don’t need to have a fully communicative set of skills here. It’s enough if you can read legal French. And this is quite sought-after.”

Expand your mind

Are Danes ethnocentric? Yes, many of them are, according to Andersen.

“The ethnocentric worldview that many Danes unfortunately have becomes widened when their norms are challenged. Every time you learn a new language you get an insight into a new way of thinking and a new worldview. You see the world through different eyes – and I think we need to see through as many different eyes as possible – as a society,” she said.

“If we don’t have sufficient foreign language skills, we miss out on all the knowledge that you can only access by knowing other languages. It’s not just about being able to say things, but about being able to consume insight from other nations – things that haven’t been translated or never will be.”

Holmen agrees: “In terms of moving about in the world, in general, I think you enter into relations in a more respectful manner if you can speak other languages. And I think it’s very important to teach this to our children. Besides, we risk having an exclusively Anglo-American view of the world because those are the only texts we can read.”

ON TO THE BRITS

Babel still in crisis

The Eurostat survey revealed that many of the citizens of Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Ireland, Spain, France and Italy are unable to speak a second language.

However, the king of them all when it comes to a lack of foreign language skills is Britain, the old colonial power who took everything but the languages, with 65.4 percent of Brits unable to hold up their end of the conversation using anything other than English. Thank god most of us speak their language, or otherwise we’ll never get that tower built.

According to iNews, some blame this failing on curricula enforced between 2004 and 2014 that language learning was only mandatory for students for three years, from the age of 11 to 14. However, since 2014, it has again become compulsory in the final years of primary school as well.

A teacher’s view

I met Susanne Richman, a Dane in her 70s who teaches in the UK, while she was drinking beer al fresco in front of the Old English Pub with her daughter Corinna. Richman, the widow of a Brit, has lived a large part of her life in the UK. She shared some of her thoughts on the British school system.

“Perhaps there is not enough emphasis in the English curriculum on children learning a second language. They’re very focused on computers – more than languages. It’s computers, computers all the way,” she recalled.

“We had German in my school and we dropped it because not enough students signed up for it, which is a shame. And now that we’re possibly leaving the EU, they think it’s perhaps even less necessary to learn other languages. Also, I think the education system in England needs to make it sound like it’s fun to learn another language – that it’s interesting and that you can gain knowledge about cultures this way. Instead of just saying ‘Pick a language’ – which is about as much advertising as you get in school. Believe me: I know, I work in one.”

A lack of communicative learning

I met Brian and Gillian Shipp in Raadhuspladsen on December 23. The British couple, both in their 70s, were on a Christmas trip to Copenhagen. Gillian told me that both of them tried to learn a foreign language growing up: “We were taught French in school.”

“But not to speak,” Brian added. “Just learning the language. You didn’t learn conversation … well, very little.”

Not much of the French they were meant to pick up remains with them today and, according to Brian, British teaching practices at the time are to blame: “I just think that the English system didn’t allow for us to learn languages easily. Whilst you need to learn the grammatical side of it, there should be a lot more emphasis on the speaking. We didn’t have any interaction. It was all about the grammar.”

Grounded in realism

Jonathan Simons, a UK government advisor specialising in education under the governments of Gordon Brown and David Cameron, has always urged realism.

“The vast majority of people in the UK who end up going into the labour market will not need to speak a foreign language,” he told iNews. Quite simply, he has always contended, it is not worth it trying to turn the tide.

However, Simons does concede that the “economic centre of the world is moving east” and it wouldn’t hurt to invest in some Chinese lessons – or other Asian languages, for that matter.

Fortunately for most Brits, an immense number of people speak their language. “That’s made us lazy I suppose,” said Gillian Shipp, with husband Brian adding: “Yes, that’s made us lazy but, you know, we’ve gained from it, really, because we can speak to a lot of people anyway.”

Just say it!

Richman attributes Britain’s failing to a widespread inhibition: “I think the English are frightened of not sounding authentically German, so they won’t speak German or any language because ‘No, no, if I don’t sound good I’m not gonna say anything’.”

Gillian Shipp demonstrated this phenomenon herself when she told me: “I know one French phrase but I wouldn’t say it to you because it’s in an English accent and you wouldn’t understand what I’m saying.”

Her husband, however, quickly demonstrated that even a Brit can mount this inner hurdle when he said: “Je m’appelle Brian.”

Indeed, as Luis Von Ahn, the founder of the language learning app Duolingo, told iNews: “The people who are best at learning a language are the ones who don’t care about sounding stupid.”