As the world waits impatiently for a COVID-19 vaccine, Denmark’s chosen candidate has hit a stumbling block following the admittance of a trial participant into hospital. It is not the only vaccine in the works, but it is the one upon which Europe had pinned its hopes.

Meanwhile, Danish medical experts offer a bitter-sweet reminder that humanity’s hopes in a vaccine may be overstated.

Instead, they contend, we should be looking to improve treatment if we are to properly overcome the pandemic.

Danish saviour on hold

Three weeks ago, a vaccine deal was landed that will give Denmark 2.4 million doses. This deal, struck by the EU, relates to a vaccine being developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, but as of yesterday trials for the vaccine have been put on hold.

READ MORE: Denmark inks coronavirus vaccine deal with the EU

The vaccine, seen as one of the frontrunners in the global vaccine race, has been suspended after a participant was hospitalised with a suspected severe adverse reaction. AstraZeneca described the response as “routine”, and the patient is reportedly expected to make a full recovery.

It is a worrying stumbling block, but the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that elsewhere there are a further five vaccines undergoing late-stage trials: three in China and one each in the US and Germany.

Denmark itself reached an important stage in developing its own vaccine when researchers from the University of Copenhagen reported the success of its mice trials in June. Clinical trials on humans are expected before the end of the year.

READ MORE: Milestone as Danish corona vaccine works on mice

Vaccinate against vaccine-hysteria

Before the setback causes too much alarm and disappointment, however, we are urged to bear in mind the clarifying if troubling fact that a vaccine is not the only possible solution to the pandemic, nor can it be expected to be a fully effective one.

Unease regarding the vaccine-hype is two-fold: not only can we expect it to still be a long time before a vaccine becomes widely available but, even when it does, it is unlikely to be the cure-all solution that some have proclaimed.

Most experts believe that a vaccine that has undergone sufficient testing will not be available until mid-2021 at the earliest. This is still much quicker than the development of most vaccines and a real medical feat but – with a second wave looming – this nonetheless seems a long way off.

Even with the introduction of a vaccine, the virus will still represent a danger. For the older community – who are typically more vulnerable to COVID-19 than their younger counterparts – vaccines generally prove less effective as their aged immune systems respond less well to immunisation. The danger for them will not disappear overnight.

An ounce of treatment worth an ounce of vaccine

Instead, it is important that we take a holistic view when looking to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. At least, this is the view emerging from Danish medical experts.

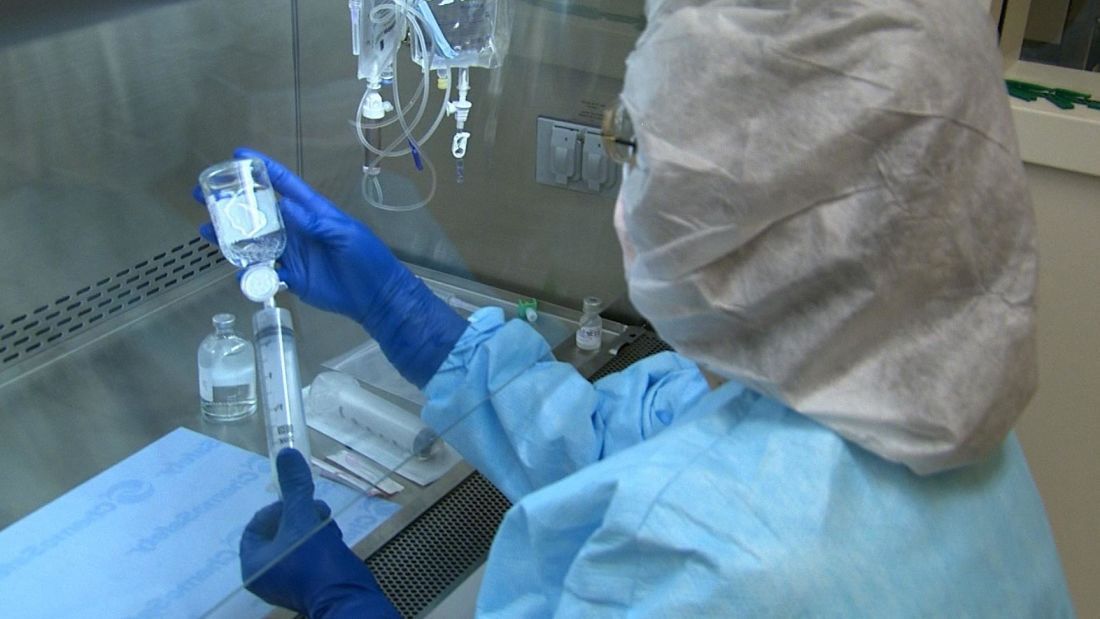

Morten Sommer, the research manager at DTU Biosustain, concedes to DR that the “development of a vaccine is fundamentally important”, but offers the reminder that “the development of improved treatment is crucial to making society function in the short and long-term”.

Improved treatment will not only make life easier for those infected before a vaccine is rolled out, but it will also help protect those who remain vulnerable even when a vaccine is available.

This is also the view of Jens Lundgren, a professor of infectious disease medicine at Rigshospitalet, who makes the worrying claim to DR that “I think most doctors would agree that we do not yet have a treatment that is good enough.”

Sommer is himself involved in the trial of a new treatment, niclosamide, which researchers hope could be significantly more effective in relieving the symptoms of those suffering from COVID-19.

A new concern

These views emerge on the back of an increasing number of reports that COVID-19 can have long-term adverse effects – both in terms of continued and previously unseen symptoms.

Lars Østergaard, a professor at Aarhus University Hospital, has described to Politiken the appearance of patients with late-stage symptoms as “completely different from anything I’ve seen before”. He reports young, healthy individuals coming into hospital with newly emerging symptoms, despite appearing to have previously recovered from the infection.

Clearly the virus impacts people in a number of different ways, but there is currently a lack of research and understanding regarding its long-term effects. Given how little time has passed (despite how long it feels), this should come as no surprise, but instead acts as a reminder that our understanding of the virus and its treatment has a long way to go.