Dansk Metal have analysed employment trends in Denmark and found that of the 33,000 new jobs created last year, one fifth were taken by locals and two fifths by non-western immigrants.

However, while non-Western immigrants have played a crucial role in Denmark’s workforce growth, only a small fraction are employed through the Positive List scheme.

This programme, designed to attract highly skilled labour, has seen surprisingly limited uptake. The programme was started originally in 2008 for so-called Highly Educated immigration from “third countries” (as in, not from the EU or Scandinavia where different rules apply).

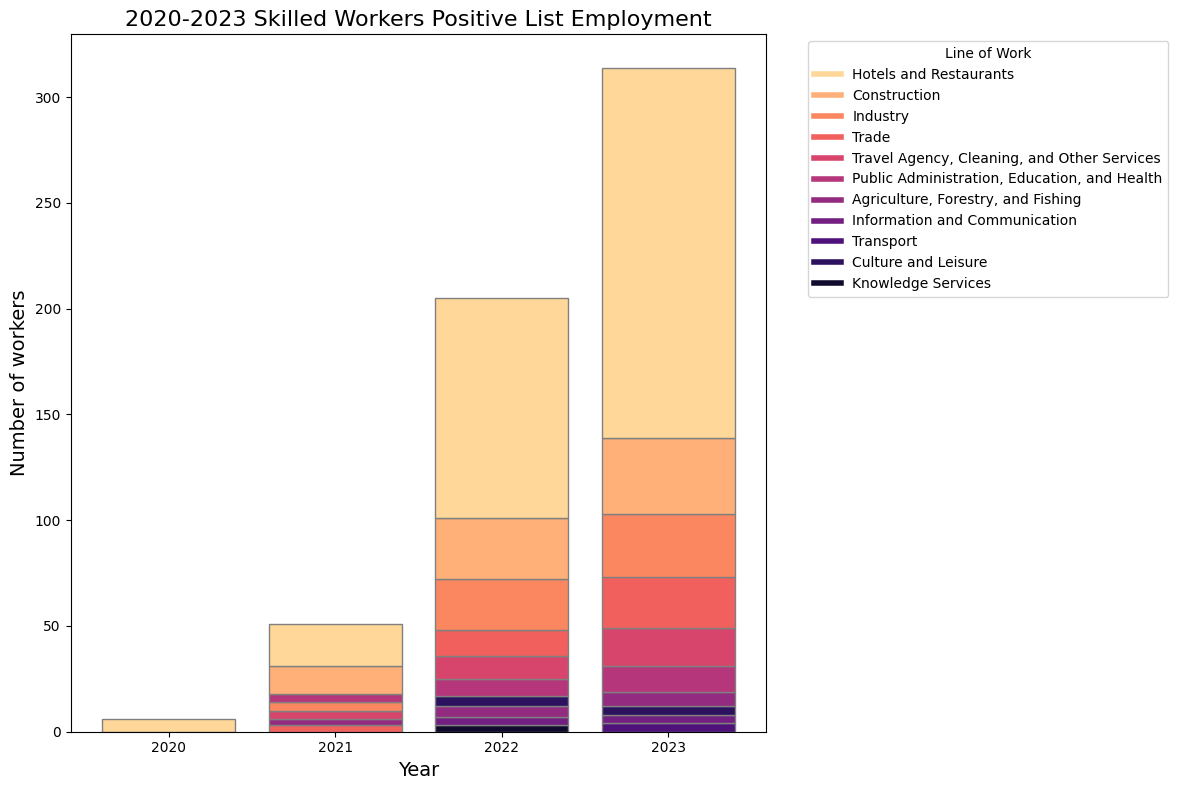

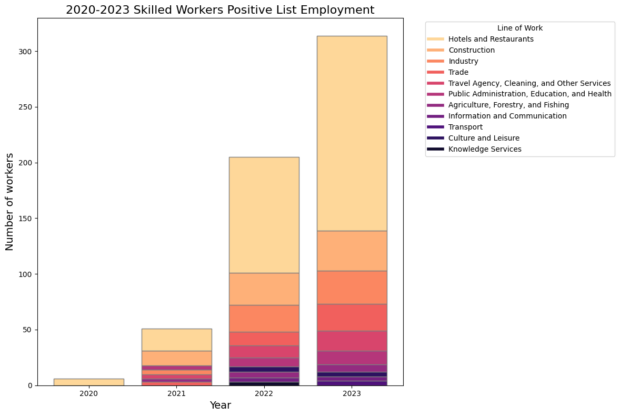

In the first year around 2000 people were employed on this residency permit but as of last year, only 40 new people were employed on this system. A need for more healthcare workers, builders and chefs was identified and so the scheme was diversified to include these industries. In 2020, the programme was broadened to Highly Skilled positions but did not get off to the best start due to the pandemic.

Peak popularity was in 2022, with around 140 new workers on this permit in Denmark but last year, there were only 100 new employees on the scheme.

Looking at the government’s analysis of the first three

years, less than a third of those who applied under this scheme were granted work permits.

Of those given this permission, just over half were chefs.

If Denmark is in such dire need of highly skilled labour, as Dansk Metal highlighted, it is a little mysterious that the Positive List is not the key route of entry for non-western immigration.

Read also: Internationals in employment set a new record: there are now 498,000

There are a couple of possible explanations. There are other ways to immigrate to Denmark as a skilled worker, for example the Fast Track scheme, which clearly has shorter processing times. Another reason could be the rules about receiving ordinary pay compared to others in Denmark make recruitment too difficult. Too little, and that is social dumping. Too much, and it makes the authorities think there is a scam in play.

Since employers must offer Goldilocks pay to the international workers, sometimes that means that they cannot attract the right people. An ordinary salary for Denmark might not be attractive to someone with highly specialised skills. Which might be where the Pay Limit Scheme is more useful.

Having three different schemes for recruiting international talent suggests there is a commitment to addressing labour shortages, yet there is a mismatch of intentions with actions when you look at the data. The system excludes many workers who could fill critical roles across various industries.

Charging over DKK 6,000 per application — especially for workers whose salaries may not match those of high-paying sectors — feels counterproductive, especially during a labour shortage. With a bit more flexibility and a little less bureaucracy, Denmark could attract a workforce that strengthens its economy. The limited use of the Positive List scheme, in particular, suggests that the current requirements and processes may actually discourage rather than support meaningful workforce growth.

Read also: Immigrants boom in trade and transport, but lack in healthcare