“People would have to leave low-lying islands, or at most, spend only a few months a year on them.” Nina Baron is an environmental sociologist specializing in climate adaptation and risk management. Speaking about these islands, she says that “One of the main challenges is that they are isolated in a way. And when something like a cloudburst or storm surge happens, they are often not prioritized very highly by emergency management, due to the low population density,” Nina adds.

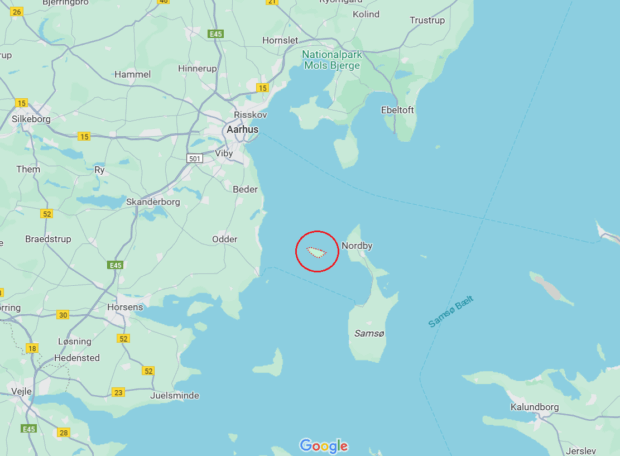

Only about 70 of Denmark’s 444 islands are inhabited. This number is also likely to dwindle in the years to come as climate change compounds the risk and frequency of storm surges, making flooding a major concern.

Crossing to the island

The wind whips around my legs as I stand on the dock in Hou. The outstretched water meets a rising sun on the horizon. My thoughts turn to the island residents. For them, crossing the water to work or to greet loved ones on the mainland is a part of everyday life.

A whistle announces the arrival of a ferry. I see “Tunøfærgen” stretched across the side. Most passengers are in their mid-40s and above. In our research, we found that Tunø has an older population, and the main reason for that is that the island had to close its school in 2022 due to a lack of students. My colleague Ida’s phone then pings. “Can we meet at the post office? I’ll be there at 10:00.”

Welcome to Tunø

We step across the threshold. A younger woman buzzes around the back of the room to the left, and another to the right. The latter is Michala Theilgaard Olesen. They both say “hej”.

Michala explains that her daughter, 21-year-old Julie, moved back to the island after finishing her education. She decided to become a farmer here. Julie’s younger brother, Daniel, has the same aspirations but is currently abroad as part of his education, and the third child, Emil, is at a boarding school on the mainland. “We have the opportunity to send them back and forth, but it’s too long of a day, so we decided to send them all to boarding school,” explains Michala.

Since the former school in Tunø was over after the seventh grade, all of them moved away when they were 14. Michala mentions that she moved back when she was 26, because she was pregnant with Julie.

“We wanted to give our kids the same childhood we had,” she says. Though the number of children was much smaller, they seemed to have enjoyed the island life. “Even though there were times I thought this wasn’t okay, I think they liked it, thank God!” Michala says, gesturing around the room.” She is juggling many possibilities for her children’s future on the island, unsure of what the best choice is. But who could choose?

“Freedom,” Michala says. I refocus my attention and notice the change in tone. “My son rode his bike to daycare on his own when he was three years old. I don’t think that’s something children could experience on the mainland,” remarks Michala.

This sense of freedom did not leave the islanders even in adulthood. Michala is able to plan her work days around her life. She tends to the church and its yard. If there is extreme rain or cold, she can always continue work at another time. “We’ve actually had big problems with the woods. Everything is so wet that we cannot go into the woods and cut down trees, and the farmers are having problems with the potatoes rotting and…” Michala went on.

Last year, Michala’s garden was underwater for about three months, and when it finally dried, very little rain was enough to flood it again. “Once it was so deep it had ducks in it – at least they were happy,” Michala laughs. “Something is changing, but if it’s just a natural change in the environment or if it’s human-caused climate change, I don’t know,” she adds.

An organic ecosystem

We cross the main road to the health center on the other side. Lars Londorf greets us, one of three nurses on the island. “I’m on call 24 hours a day, two to three weeks a month,” he says.

Tunø is a small community of 75 inhabitants, or a big family as Michala said. That

means that Lars takes care of people he knows very well. “It’s a part of the job and I can handle that, but it’s of course hard,” he says. He admits that he leaves the island during his spare time. “I’m not a nurse, I’m… me then,” he explains.

Lars handles emergencies and primary care. He visits people who need help, replenishes the stock of medical supplies, and prepares for the doctor’s visit once a month. If he cannot treat his patients, he calls for help from the mainland. “I receive emergency calls almost every week, but only 10–15 helicopters come here per year. The majority of them are called in during the summer when there are more people on the island,” says Lars.

It takes under an hour for the helicopter to arrive. “It’s a longer response time here than on the mainland,” he adds. Other islanders spring into action if extra help is needed with the fire engine or the ambulance. Tunø is a car-free island, so the ambulance is the only permanent car on Tunø. Tractors were the main means of transport back in the day, now they rely on bikes or golf carts.

The snow is still falling when we walk outside. A tractor passes by, and Lars points out the house where the driver can be found.

A lost childhood

I spot the tractor in the backyard. Vagn Olesen leads us into his house, which was once a bakery—a fact he knows well, having been born and raised on Tunø. Freedom is a keyword from his childhood, as it was for Michala. He had his own boat to go fishing and drove tractors already when he was 4 years old. “We had to put a 5-kilo bucket on the pedal, because we weren’t strong enough to press them down,” Vagn remembers.

In the seventies, there were over 120 islanders on Tunø, around 25 of whom were children. Today, there is only one. There are also a few permanent jobs on the island. Vagn works down at the harbour alongside his wife. He believes the lack of career opportunities hinders others from moving here, but he can’t imagine living anywhere else.

“There is no snow anymore, but there was snow up to my head when I was a kid,” he says. Vagn thinks that the big storms in recent years could be related to climate change. Due to Denmark’s geographical position, surrounded by two large seas, it is not surprising that the country is prone to coastal flooding and storm surges.

Climate change is expected to increase the likelihood and frequency of storm surges, from a once-in-100-years event to something that happens every 20 or 25 years. The frequency of such events has already increased in the last four decades around the Wadden Sea. The lowest lying islands are only about 2 meters above sea level. And sea levels are rising rapidly. A 1.2-meter rise is expected within the century.

Preserving Tunø

Ida and I walk down Vagn’s gravel drive, and as we trudge further down the road, we arrive at a lookout point. It gives us a 360-degree perspective of the entire island – from the thicker woods, to the beaches, some farmland in the west, the harbour, and the entire village back to the east.

Michala, Lars, and Vagn all have something to give to this microcosm of life. Perhaps they have something that non-islanders lack—like a strong sense of community. But they also certainly did not give us the answers we were expecting. They each know that something is happening to Tunø. Still, their individual lives, responsibilities, and memories of the island matter more. Caring for the next generation and cultivating the island come first.

I think back to the conversation with Nina, the environmental sociologist. What is the future of this old farming community going to be like? “I think we can change the way we use these islands. We may not be able to farm the way we once did, but perhaps we can enjoy the islands in a new way. They don’t have to lose everything,” she said.