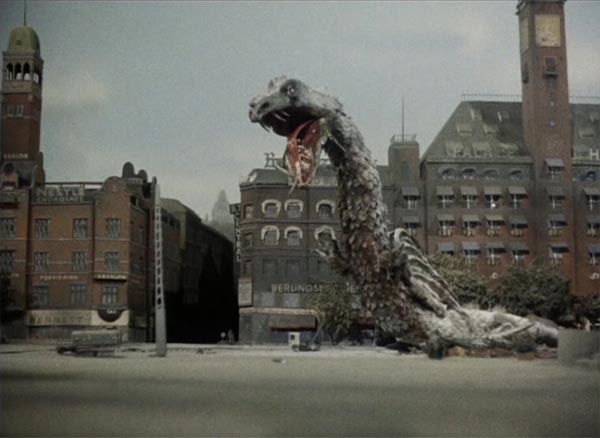

In 1961, Copenhagen was held in an icy grip of terror as a recently-thawed, 90-foot monster, found frozen in the Arctic Circle, wrought havoc throughout the city. Known only as Reptilicus, the beast had an insatiable appetite for Danish farmers and an uncanny knack for avoiding bullets, grenades and rocket launchers …

Born in 1917 in Copenhagen, the screenwriter, director and novelist Ib Jørgen Melchior lives in his adopted hometown of Los Angeles with his wife Cleo Baldon. He has a life story that is in itself worthy of a movie: the son of a Wagnerian tenor, Melchior saw the classic American horror ‘The Man Who Laughs’ (by Paul Leni) in 1928 and became enamoured with motion pictures.

After graduating from Copenhagen University, Melchior began travelling as a theatre actor and this eventually took him to Broadway. In 1941, Melchior joined the war. He became decorated for his services within the ‘Office of Strategic Services’, which would eventually become known as the CIA.

Later in New York, Melchior worked as a director in live television before heading to Hollywood to realise his dream of directing for the cinema. Upon his arrival he soon discovered that despite having worked as a director in New York, one needed to be a union member in Hollywood in order to direct a film there. However, without a Hollywood directing credit, it was impossible to join the union. Producer Sid Pink, well-known for his frugality, agreed that if Melchior could deliver a script at minimum cost, he’d allow him to direct it – for minimum payment. That film was ‘The Angry Red Planet’. It was a box-office success and AIP (American International Pictures) commissioned two more films from Melchior and Pink.

Aquarium-born carnage

Their next film was to be ‘Reptilicus’. Melchior recycled many elements from his abandoned script called ‘Volcano Monsters’ and, thanks to contacts in Denmark, he enabled Pink to generate Danish finance for what would be a rare Danish-American co-production. It would be shot at key locations around Copenhagen with both Danish and English language versions made simultaneously.

The narrative follows the discovery by miners of an ancient reptile frozen underground. The beast’s tail is returned to Denmark’s Aquarium, which serves as the central location for most of the film’s narrative. Under closer inspection, scientists learn of the creature’s ability to ‘regenerate’. Like a starfish or a worm, Reptilicus can grow a whole new self from any severed part. Before long, the tail has grown a body and Copenhagen is host to a pre-historic monster.

In fact, the city is very well served by ‘Reptilicus’, with one central sequence acting as a travelogue of sorts: two American characters go for a drive and as we’re treated to a montage of all the sights, we hear enthusiastic commentary from the actors: “Look, the Little Mermaid, how lovely – it is a beautiful city.”

A case of Pink eye

Despite the understanding that this would be Melchior’s next film as writer-director, Pink made the surprise declaration that he was to act as both producer and director of the picture. Pink had never directed a single frame of dramatic fiction before, nor did he understand a word of Danish. Understandably Melchior was concerned. “It takes more than just wanting to direct a film, you have to have some knowledge of it, but unfortunately Mr Pink had none,” he recalled.

Pink also credited himself as co-writer, but as Melchior recalls, Pink’s only contribution to the writing was the removal of anything he feared he couldn’t handle directing. Melchior recounts (undoubtedly with some amusement) one anecdote that clearly illustrates the extent of Pink’s inexperience. During the filming of a set-piece involving hundreds of extras and the raising of the Langebro Bridge, supposedly as a means of preventing Reptilicus crossing it, the nation’s press were gathered. Many athletes were poised to hurtle themselves off the end of the bridge in this huge scene, which one could really only shoot once.

“Wisely enough, Pink had six cameras in different positions, shooting this scene. However, not being used to directing, Pink forgot to call ‘ROLL’ for his cameras. He just yelled ‘ACTION’ and everybody ran but he never rolled his cameras. Fortunately one camera man was smart enough to see something was wrong and rolled. We got one shot and everything else was gone.”

A monster turd

Pink’s finished cut was rejected by the studio and Melchior was called in by producer Sam Arkoff to see if he could save the picture: “It was so bad that American International refused to release it. So I doctored up ‘Reptilicus’. I did some re-editing, putting in extra scenes and cutaways that we made without actors, and the end result was that AIP accepted the film and distributed it.”

Pink and Melchior rarely spoke following their commitment to AIP. Melchior was awarded the Golden Scroll (now Saturn Award) in 1976 from the Academy of Science Fiction for his body of work. By that time Pink had become an exhibitor, running cinemas in Puerto Rica and Florida, before passing away in 2002.

Today Melchior reflects knowingly on the film’s cult status: “‘Reptilicus’ is kind of a classic, because it is both good and very bad. Somehow the very bad augments the good and it becomes fun. It cannot be designated as a great film by any stretch of the imagination, but it is probably in some instances much more fun than many so called ‘great films’.”

Gone and almost forgotten

The closing line of dialogue in ‘Reptilicus’ refers to the monster: “It’s a good thing that there’s no more like him.”

Ironically the credit ‘Produced and Directed by Sidney Pink’ follows shortly after.

Ib Melchior’s 2009 book ‘Six Films From The Sixties’ chronicles the production of ‘Reptilicus’ in great depth. A special thanks to Brett Homenick and his excellent blog sidelongglancesofapigeonkicker