Climate change was thrust back into the political spotlight today as the government presented the second stage of its plan to reduce carbon emissions.

The government wants to cut carbon emissions by 40 percent in 2020 compared to 1990 levels. While last year’s energy plan to transition to renewable energy sources found the majority of these cuts, an additional six percent still needs to be cut in order to reach the target. Today’s plan outlined 78 ways that these cuts could by found by reducing emissions in the transport, agriculture, building and waste sectors.

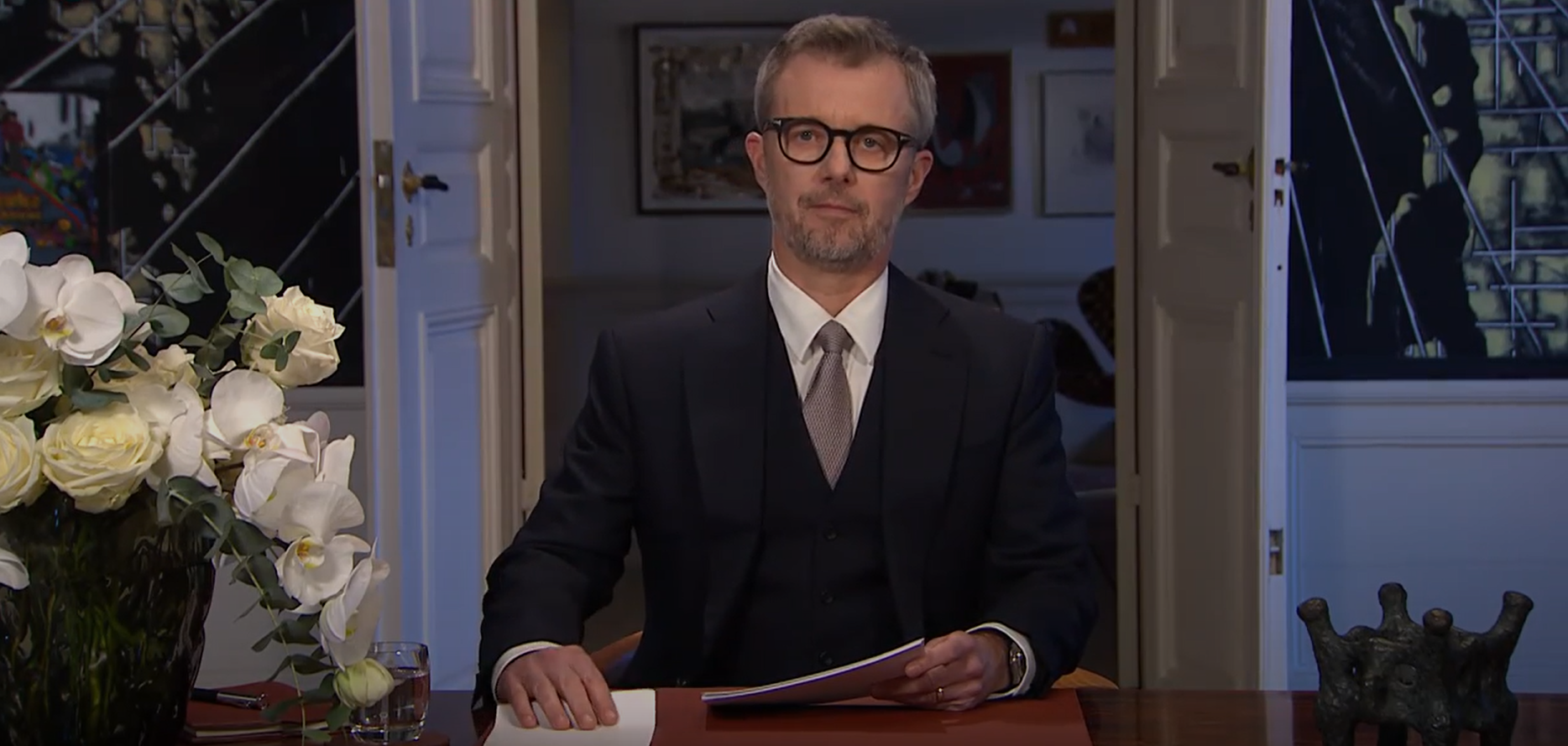

“Climate change is happening right now and over the span of a few decades, the living conditions for millions of people across the world risk getting worse,” the climate minister, Martin Lidegaard (Radikale), stated in a press release. “That’s why we have an ethical duty to act. Denmark is a rich country and we have the opportunity to lead the way. That’s what we will do with our climate plan.”

Prior to today’s presentation, Lidegaard stated that he hoped to find ways to reduce carbon emission by making it easier for people to choose more climate-friendly behaviour, rather than making it more expensive for businesses to pollute.

“We each need to act where we can,” Lidegaard stated in an op-ed in Politiken newspaper last week. “This applies to both our professional lives and personal consumption. It applies to residents and it applies to the state. Every little nudge will change both the market and the political mindset.”

Still, the government admitted in a report accompanying the plan that, “at the moment it won’t be possible to reach the 40 percent target in 2020 without incurring costs”.

Not set in stone

The government announced that it intends to present a Climate Law in the coming parliamentary year to guide future efforts to cut carbon emissions.

The catalogue of ideas will primarily be used by to improve ways of integrating climate strategies and targets into efforts to improve growth, competitive ability, and public finances.

“The climate plan does not give a here-and-now solution for how to reduce emissions or which concrete initiatives should be implemented and when,” the Climate Ministry wrote in its plan. “There is considerable uncertainty about how far we are from reaching the 40 percent target and how much EU initiatives will contribute. That is why the scale of the necessary extra national initiatives are not yet known.”

For each idea included in the catalogue, the government calculated the costs to the state, businesses and individuals and compared those to the potential emission savings.

For example, increasing the insulation requirements for windows could reduce carbon emissions by 59,000 tonnes in 2020 and lead to a net savings for the national economy of 57 million kroner.

Reducing the speed limit on motorways from 130 km/h to 110 km/h is less effective, however. While it could cut 63,000 tonnes of carbon emissions in 2020 and save drivers around 230 million kroner a year in fuel costs, the added costs from longer travel times mean that each saved ton of CO2 will actually end up costing around 13,500 kroner.

Mixed responses

The list of ideas was leaked ahead of time to the national press (The Copenhagen Post requested, but was not granted, an advance copy) and by Tuesday, the opposition had already condemned the government for wanting to impose extra costs on taxpayers.

Lidegaard defended the plan, however, and argued that the list was simply designed to show potential areas for carbon cuts and evaluate their costs. Reducing the speed limit would not be considered any time soon because it would result in little carbon savings compared to the costs, Lidegaard said.

While industry lobby group Dansk Industri (DI) said it could not support any initiatives that made it more expensive to run a business, but welcomed ideas that could both improve the economy and reduce emissions.

“The current registration fees on private vehicles are based on the vehicle's worth,” DI director Karsten Dybvad told Ritzau. “This should be replaced by a levy that depends partially upon the amount of CO2 that the car emits. […] This would increase turnover without reducing the ability to get around. The taxation on cars is currently way too high.”

Other groups were disappointed that the government was trying to play down using any new fees and levies to bring down carbon emissions.

“When the argument against it is the economic crisis, we should not rule out that as we approach 2020 that we could try using fees such as road pricing or cutting the deduction to the energy levy that is given to the trade and service sectors,” Greenpeace spokesperson Tarjei Haaland stated in a press release, adding that many of the government’s ideas could easily be implemented.

“Some of the best ideas that give considerable reductions are giving subsidies to farmers who transform agricultural land into meadows and forest, as well as installing more wind energy in another offshore wind farm.”

While there is the potential to find significant cuts to carbon emissions in agricultural sector, agricultural lobby group Landbrug og Fødevarer argued that the government risked losing jobs and production.

While there is the potential to find significant cuts to carbon emissions in agricultural sector, agricultural lobby group Landbrug og Fødevarer argued that the government risked losing jobs and production.

“We produce our milk, eggs and meat with less carbon emissions than pretty much any other country so it makes no sense to the climate or the Danish economy to punish the best in the class,” the group's deputy chairman, Lars Hvidtfeldt, stated in a press release, adding that the agricultural sector had already reduced emissions by 23 percent since 1990.

Among the ideas targeting agriculture are proposals to cover slurry tanks, reduce the levy deduction for agricultural fuel and cutting the use of nitrogen fertiliser by ten percent, but Hvidtfeldt argues that these could have “enormous economic consequences”.

Ambitions resting on EU policy

Which initiatives the government chooses to implement depends on how far emissions need to be cut to reach the target. While the current estimate is around six percent, this could be significantly reduced if EU policies make it more expensive to emit CO2.

The problem is that the price of a permit to emit a ton CO2 on the European carbon trading market (ETS) is currently about a tenth of what it needs to be if it is to spur consumers and businesses into investing in low-carbon solutions.

An explanation for the low price is that there are too many surplus permits on the market, which led the commission to temporarily withdraw 900 million tonnes from the market until 2020.

This so-called ‘backloading’ has not had an effect on the cost of carbon and has led critics to argue that the price will not rise until the withdrawn credits are permanently removed. This in turn requires that the EU increases its ambitions for carbon reductions beyond its current 20 percent target for 2020.

“Because our national policies and EU policies are interdependent, the government will work to stabilise the EU’s carbon market in the short term, so that the target for 2020 is increased and that a new ambitious target is set for 2030,” the government stated in today’s plan.

Fact box | Climate plan

Denmark set a goal of becoming entirely free of using fossil fuels to produce energy by 2050 in last year's green energy plan.

The energy plan set a target to reduce CO2 emissions by 40 percent in 2020 compared to 1990, but only committed to cuts of around 35 percent.

Today's climate plan outlines 78 different ways that the transport, agriculture, building and waste sectors can cut their emissions and contribute to reaching the target.

The amount of cuts that need to be made depends on the cost of emitting CO2, which is decided on the European carbon trading market.

The cost of emitting CO2 is currently very low and Denmark needs the EU to set more ambitious emissions targets before the price will rise.

The government will present a Climate Law in the next parliamentary year to guide its carbon reduction ambitions.

The government's climate plan and list of potential cuts can be found here (in Danish).