What happens in art when a modern, industrialised European culture meets an exotic, outside, foreign influence? An exhibition now on at the National Gallery of Denmark provides some answers by highlighting the influences that Japanese art had on Nordic painters.

In the second half of the 19th century, a wave of enthusiasm for all things Japanese swept across the Western World. From around 1853, Japan had gone from being an extremely closed, somewhat enigmatic society, to opening up to the West through trade. Japanese art and artefacts were suddenly being exhibited at world’s fairs – and attracting great attention from the public.

‘Japonism’, as the craze was called, was first popular in France and Britain and spread to the Nordic countries a little later. Artist and art critic Karl Madsen published a book entitled ‘Japanese Painting’ in 1885, and because it was the first work on the subject in a Nordic language, it was very influential in that part of the world.

More mannerism than movement

Initially, Japonism was more of a mannerism than an art movement. It permeated popular culture in the form of photographs, posters and ceramics, in which Japanese motifs were incorporated. Copenhagen Zoo had a poster featuring a samurai in full armour; props such as parasols, kimonos and screens with bamboo designs began to appear in homes and paintings. Bohemians even photographed themselves and their friends in Japanese dress.

Anders Zorn’s painting ‘The Misses Salomon’ shows just such an intimate domestic scene of the kind depicted in many Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, in which a colourful Japanese screen provides a backdrop to a kimono-clad sitter who is having her hair done. For all the world, she could almost be a geisha and her assistant.

Commenting on the trend in 1899, Oscar Wilde said that “in fact the whole of Japan is a pure invention. There is no such country, there are no such people … the Japanese people are simply a mode of style, an exquisite fancy of art.”

Focusing on design

However, the second phase of Japanese influence proved more fruitful. Artists studying Japanese woodcut prints became fascinated by their graphic qualities – the zooming in on the foreground, daring use of cropping and odd angles, the very flat images, and the intense, but simple colour schemes. Japanese prints also often emphasised simplicity and economy of image; a depiction of a spider in a web on a plant could be a work of art in itself.

Danish artist Henriette Hahn-Brinckmann was one of the artists who, through seeing Japanese prints, rediscovered the coloured woodcut around 1900. She had an excellent eye for the imagery and devices used, and this is perfectly illustrated in her portrait of the sculptor Niels Hansen Jacobsen entitled ‘Evening’. The flat image and delicate, but simple framing are very much like the prints that she so admired.

At the time, a number of artists saw the devices and techniques derived from prints as a liberating influence that could open up alternative artistic directions. For several Danish women artists in particular, Japonism was a liberating experience that enabled them to emerge from out of the shadow of the male-dominated art world and its conventions.

The natural world

The second part of the National Gallery exhibition sees works grouped into four themes under the headings of ‘trees’, ‘waves’, ‘the micro cosmos’ and ‘winter landscapes’.

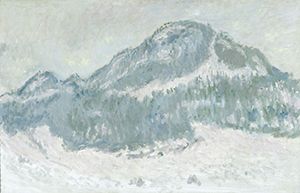

Nature – and the accurate depiction of it – have always been important elements in Japanese prints and this, too, rubbed off on the Nordic artists, as it had also done on some of the French impressionists. Claude Monet, for example, found his own version of Mt Fuji in Norway in a painting of Mount Kolsaas.

To the Nordic artists, Japanese art offered them an exciting new way of seeing, interpreting and depicting their own landscape. The effect of this could perhaps be likened to that which the world of antiquity had on Renaissance art.

Stylistic overlaps

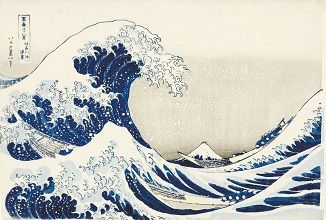

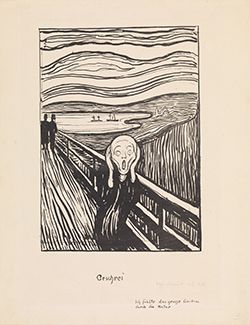

There is a great deal of interest to see in this exhibition. For example, under the theme ‘waves’, the famous image by Katsushika Hokusai entitled ‘The Great Wave Off Kanagawa’ is juxtaposed with a black and white version of the same motif and a black and white print of Edvard Munch’s ‘The Scream’.

The idea here is to draw a parallel between the stylised wave form in the Japanese print and the wavy sky which appears in the background of the Norwegian print.

Munch features several times in the exhibition. His lithograph ‘Harpy’ seems to have a definite connection to a Japanese woodblock print of a swooping eagle – via a watercolour by Danish artist Elise Konstantin-Hansen entitled ‘Vulture’, which Munch had seen and admired at an exhibition in Copenhagen.

It is also almost impossible to see the picture ‘The Artist’s Wife At The French Windows’ by LA Ring without parallels being suggested to the likes of Utagawa Hiroshige’s ‘The Plum Garden at Kameido’. Ring’s wife may appear to be depicted in a very Danish domestic setting, but the treatment of the cherry tree outside certainly shows more than a nod to Japanese prints. To emphasise the connection even more plainly, the exhibition includes a Van Gogh study of the Hiroshige print, which is almost identical to the original.