Immigrants and their descendants, along with outraged Danes, were not the only ones left reeling when Parliament suggested on February 9 that immigrants and their descendants could not be Danish.

READ MORE: Poor wording in resolution denies ‘Danishness’ of some immigrants

Parliament felt it was well-advised to officially respond to the news that there are now two postcodes in Denmark where the majority of people are immigrants from non-Western countries.

READ MORE: Immigrants and their descendants now the majority in two Danish neighbourhoods

However, several adoption groups and adoptees feel the statement was ill-advised, with one South Korean adoptee calling the official statement “outrageous”.

Outraged, worried, awkward

“I am extremely worried this has happened,” Kim, a 26-year-old adoptee who arrived in Denmark as an infant in 1990, told CPH POST.

While Kim concedes that the impact on non-Western adoptees will probably be minor, that hasn’t stopped him from feeling “uncomfortable” in the only country he has ever called home.

Only fractionally Danish?

Sharing Kim’s concern were two Danish adoption services, Adoption & Samfund Ungdom (ASU) and Adoption & Samfund (A&S), which issued a joint statement on February 14 to register their displeasure with the language in Parliament’s statement.

“The feeling that we are not accepted as Danish is an unbearable feeling for all of us,” said the groups in a joint statement.

“Does this now mean that international adoptees in Denmark must think of themselves as non-Danes? Should everyone now be divided into categories like half-Danes, quarter-Danes or full-Danes?”

False claims

The think-tank Tænketanken Adoption disagrees. It made a statement on Facebook on February 15 seeking to give the statement important context.

“The approved statement must be seen in the context of decades of anti-Muslim racism in Denmark – it is directly targeting Muslim minorities and asylum-seekers. Yet this important aspect is not even mentioned in Adoption & Society’s statement,” Lene Myong, a researcher at the University of Stavanger who is a member of TA, told CPH POST.

“It falsely claims that transnational adoptees have been stripped of their right to freely choose where to live in Denmark. This is not true. You are defined as a Dane if one of your parents holds Danish citizenship and is born in Denmark. As adoptees we are categorised as Danes because our adoptive parents are Danish. The Danish state does not recognise kinship between adoptees and our first (non-Danish) parents.”

Still collateral damage

However, Michael Paaske, the executive chairman at A&S, claims that TA “missed our point” and that “the adoptees are heavily impacted by this”.

“These words by Folketing [Parliament] put Danes and non-Danes into two different boxes, and this is not good for anything, neither for the adoptees nor for all other people in Denmark with a foreign background,” he said.

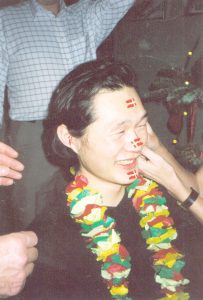

Jes Eriksen, 37, who was adopted and brought to Denmark in 1980 from South Korea, agrees.

“I don’t think adoptees were the prime target of this specific event. But we’re still going to be hit by it,” he told CPH POST.

“The problem is that we’re still collateral damage in terms of the way we are treated by strangers since most people can’t really tell an adoptee from an immigrant. Until people hear you speak and maybe talk to you, they only judge you by your appearance. And having to constantly need to legitimise yourself in society is really stressful. If immigrants were treated better overall, we’d be treated better as well.”

Already a sensitive subject

Parliament’s statement is not legally binding, and Jacob Ki Nielsen, an associate researcher at the University of Copenhagen, believes it will not affect transnational adoptees in Denmark because “most have been naturalised upon arrival and accordingly have the legal status ‘Danish origin’ (dansk oprindelse).”

However, according to Hans Christian Riis, 29, who arrived in Denmark as an infant in 1987 from South Korea, that will be scant consolation for the many adoptees who already have mixed feelings, whether they feel more attached to the countries they were born in, or hate them for not wanting them.

“Danishness or your sense of belonging is quite a sensitive matter of discussion for many adoptees. There are many perspectives,” Riis told CPH POST.

“Those who see themselves as purely Danish and have no ties to the adoption country: what would happen if they are labelled by the government ‘non-Danish’? After all, ‘Danishness’ is indefinable, so when you start to question someone’s integrity and pride, that can be dangerous.”

Words of wisdom

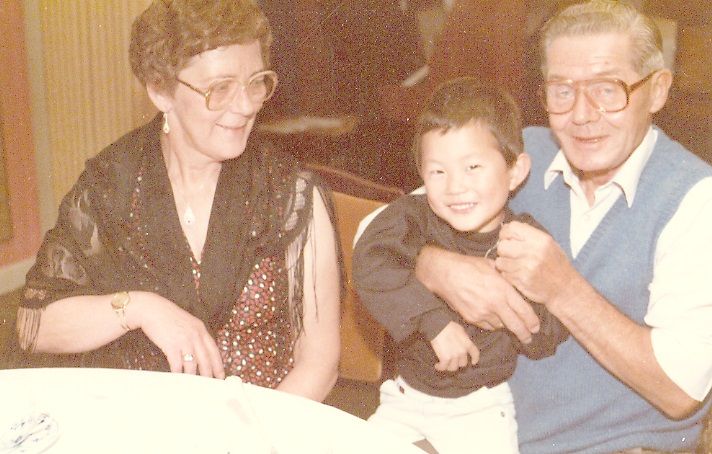

His Parliament might have let him down, but at least Riis can rely on some of his fellow Danes for rational thought: his parents.

“My parents said: you are as Danish as one could be and that sometimes decisions are made without proper thoughts,” he said.

“Plus, I shouldn’t care about it at all.”