The commission on one of the most sensitive subjects in Danish politics has now published its findings.

A hot issue

Dagpenge, the unemployment insurance, has been a hot issue for several years now. Being a member of an insurance scheme like A-kasse (as long as you have been one long enough) entitles you to support in the case of unemployment – members contribute individually to it, but there is also considerable government funding – and the support period used to be a generous four years.

But three years ago it was generally accepted that four years was too much. So it was then cut to two years in consideration of the relatively low unemployment figures. And the questions that followed asked how many would be affected.

More than expected

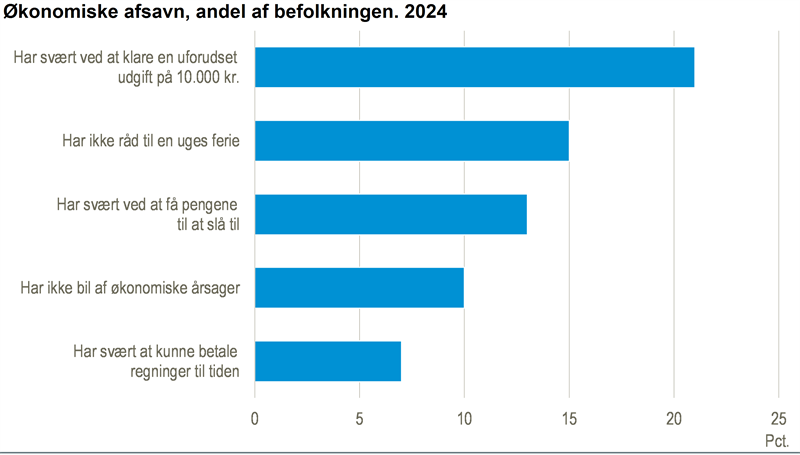

The reduction to two years cost 30,000 people their benefits, forcing them to find any job they could, or leaving them just with the next level of public support, kontanthjælp, which is less generous and depends on household income and savings. That number was far more than expected.

It is now expected that the period might be extended to three years again and that becoming eligible might become a little easier. All of this, of course, is in the interest of getting more people employed, securing their livelihoods and giving them the incentive to take unsuitable jobs if the right one is not at hand.

Seen in context

Compared to other countries, this system would seem to be rather generous, but it has to be seen in relation to a Danish model in which the general assumption is that conditions in the labour market are negotiated between employers and employee unions.

That goes even for public servants when the government or municipalities are negotiating conditions and using labour market instruments against each other. Not long ago, negotiations broke down between the municipalities and teachers, and a lockout was set up against the teachers until they had accepted new terms for working hours at public schools.

Advantage of flexicurity

The Danish model has an advantage which is special. It’s is called flexicurity. On the one hand there is a rather high unemployment benefit. And on the other, it is easier for employers to lay off staff than in many other countries.

Across the political landscape, there is consensus about on the one hand keeping the Danish model as a tool in the growing international competition and on the other finding a balance between insurance payments, dagpenge and the mere life-support payment, kontanthjælp. Not an easy task. It’s worth taking a quote from national comedy writer Holberg to ask: “What are we to do when they are all right?”

Austerity not an option

In Danish politics right now, no party is keen to bring in more austerity and there is even less inclination to be forced to roll back on the too generous handouts if unemployment increases.

The commission has delivered a model which is a zero sum solution and it seems that the responsible political parties – somewhat reluctantly – are forming a solid majority, so the sensitive issue can be dealt with quickly and the labour market can go on with the Danish model, hoping that the problem will go away if more jobs are created.