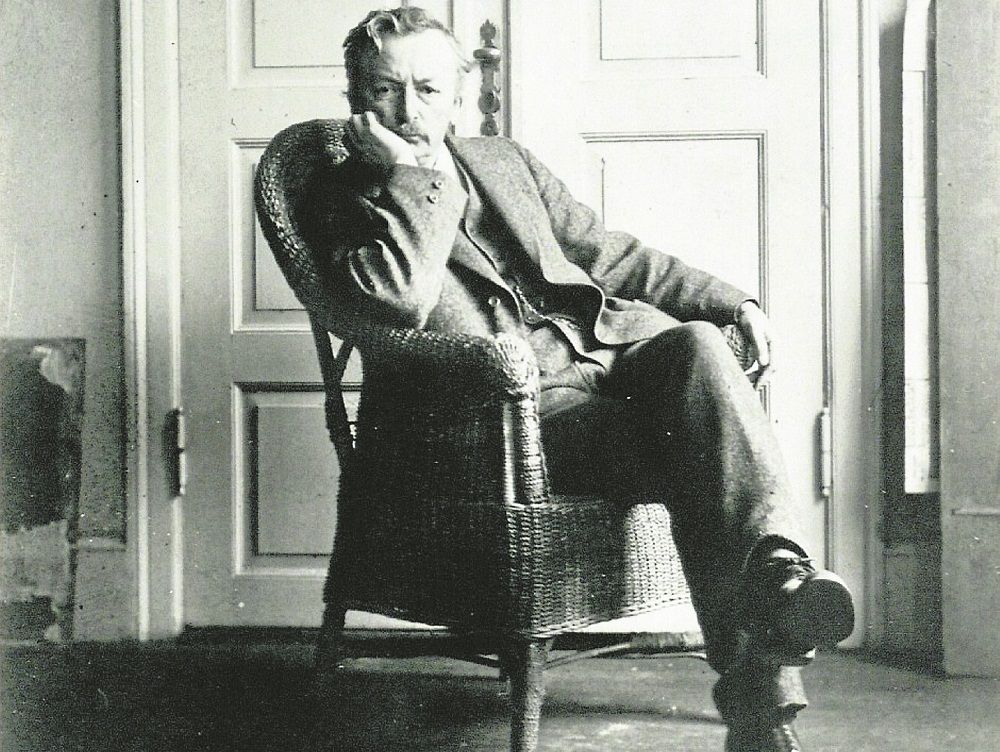

In 19th century Copenhagen, the respected art critic Karl Madsen called the reclusive artist Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916) “the weirdest soul ever to grace Danish painting”. And in his lifetime – an early death from throat cancer silenced the already quiet artist – the majority of critics decried the work of the taciturn artist, who painted in several shades of grey with the occasional splash of black, as boring.

Today, though, Hammershøi is experiencing a revival in popularity – among his fans is the British actor Michael Palin, who made a programme about him. Those that love his work can see far beyond the grey, finding fields of subtle colour in his shadowy canvases. And it’s unsurprising to note that the National Museum (Statens Museum for Kunst) is currently displaying a retrospective of his work, ‘Hammershøi and Europe’.

Hammershøi, who was born into a middle class life in Copenhagen, showed talent for art at an early age. His family supported his talent, especially his mother, and he was able to attend the Danish Royal Academy to study his craft. At school, his colleagues found his work confusing. One of his teachers, the prominent Danish artist PS Krøyer (1851–1909) who was famous for painting sunny beach scenes full of light and colour, maintained a love-hate relationship with the young artist. He first compared Hammershøi’s images to “foetuses in alcohol”, but then acknowledged that although he did not understand the almost monochromatic work Hammershøi was producing, he expected him to be successful and would therefore leave him alone.

Establishment unimpressed

Hammershøi made his debut in the Copenhagen art world in 1885 when he submitted a portrait of his younger sister Anna to be judged by the Danish Royal Art Academy for an important art prize. In the portrait, Anna sits alone, dressed in black, her head cocked anxiously to the side. The painting defied artistic conventions of the time, which favoured including significant objects around the subject of a painting to create a layer of symbolic meaning. Unsurprisingly, Anna’s dour portrait was passed over by the academy. However, even though the establishment was unimpressed, the subdued Hammershøi had developed a following among his colleagues and peers, and the loss of the prize prompted a public outcry from 41 of his fellow artists who supported and admired his work. As Madsen observed, with the portrait of Anna, Hammershøi had thrown down the gauntlet to the academy.

The controversy prompted his fellow artists to create an alternative to the annual painting exhibition at Charlottenborg, which many spent their entire careers bidding to be included in. In 1891, the group created The Free Exhibition, which is today housed at Den Frie Udstillingsbygning in Østerbro. Though he seemed to be surrounded by debate and turmoil, Hammershøi went on quietly making his work, hardly bothering to participate in the uproar.

In fact, Hammershøi wasn’t even around for the Free Exhibition, having married Ida Ilsted in 1890. The pair departed from Copenhagen to tour European capitals. Rather than spend the honeymoon by his wife’s side, however, Hammershøi often left her to visit museums and meet artists, conducting research as part of his personal artistic education. Ida and Hammershøi continued to travel often throughout their marriage, to Paris, London, and through Italy and the Netherlands, but their Copenhagen home at Strandgade 30 would prove to be the artist’s greatest inspiration.

Oldies but goodies

It was at Strandgade that Hammershøi created the studies of empty rooms for which he is famous. The couple moved to this Copenhagen address in 1898 and the artist began his methodical study of rooms, doors, windows, and every other possible architectural configuration, making over 60 paintings of the flat. Many of the paintings from Strandgade, with titles like ‘Dust Motes Dancing in the Sunbeams’ (1900) or ‘White Doors or Open Doors (Strandgade 30)’ (1905), are empty of people and objects, showing only the rooms and the light contained within. Hammershøi, in a rare interview, stated that he just liked the mood of old houses. When the artist did add a person to his sparse canvases, it was most likely Ida. She is, however in keeping with Hammershøi’s convention of flouting tactics, often portrayed with her back to the audience. A typical painting like ‘Interior. Young Woman seen from Behind’ (1904) shows Ida engaged in unknown domestic business, dressed in black, her back to the viewer, with her neck – arched slightly to the side – as the most animated part of the painting.

Hammershøi largely ignored the society of his contemporaries, preferring to keep to himself. However, he did seek a connection with the American-born, British-based artist James Abbott Whistler, another controversial figure in contemporary art circles, who painted in a way that defied categorisation. The Danish artist admired him, probably because he saw a kindred spirit in Whistler’s artwork. He even painted his own version of Whistler’s most famous painting, the austere ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1’ (1871), which is commonly referred to as ‘Whistler’s Mother’. When visiting Hammershøi and Europe at the National Musuem here in Copenhagen, visitors will see that curators have organised Hammershøi’s paintings alongside the work of artists that both inspired and were inspired by him, including paintings by Whistler.

Foggy London town

Unfortunately, on Hammershøi and Ida’s several trips to London, he was never there at the same time as them. Unable to find inspiration in a friendship with a like-minded artist, Hammershøi was instead inspired by the London fog. The grey mist of the British city can be seen in several of his canvases from this period such as ‘Street in London’ (1906).

Madsen, a reluctant supporter of Hammershøi, tried to classify the artist’s unclassifiable style as ‘neurasthenic painting’, derived from the psychoanalytical term neurastehnia. Neurasthenic patients displayed fatigue, anxiety, and depression, believed to be the side effects of industrialisation. Perhaps Hammershøi’s depressive art was actually reflecting the temperament of a society moving into the modern age.

Beyond one dramatic incident in 1907 when Hammershøi and Ida were mistakenly arrested by Italian authorities for forgery, the drama in this Danish master’s life only played out on his canvases. He developed and maintained his stark artistic vision, and it is for this that he is remembered today.