It’s often reported how the author of ‘Game of Thrones’ partly bases his books on the state of England during the Wars of the Roses, a bloody 30-year affair in the late 15th century.

READ MORE: This is I, Hamlet the fake Dane

Continuing to shake our world

However, you could argue he owes more to Shakespeare – not least the Bard’s exaggerated villainy of Richard III, a nearly winner of that barbaric war – and his tragic plays.

‘Hamlet’ and ‘Thrones’ have a lot in common, whether it’s regicide, fratricide, the walking dead, icy fogs, antiheroes, raging passions, treason, skulduggery or incest.

And in HamletScenen and London Toast Theatre’s new modernist outdoor production performed against the backdrop of the Renaissance castle Kronborg –the play’s very own Elsinore – passing seagulls deputised for dragons as the heavens brought winter crashing down onto the stage and audience.

But they were too transfixed to care. After all, didn’t somebody once say that in bad weather: ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer, or words to that effect?

In the path of the human tornado

Director Lars Romann Engel and lead actor Cyron Melville go the full antihero hog with their depiction of Hamlet, a human tornado who ruins the lives of everyone who crosses his path.

This Hamlet’s so unlikeable he elicits sympathy for Uncle Claudius and even has a punch-up with Horatio. He’s the kind of man who graphically grabs his groin to illustrate sexual euphemisms – no wonder his prospective father-in-law is so wary of him.

Any aversion to blond Hamlets (we blame Olivier) disappears in the final scene of the first act, as Melville delivers on the promise of a pulsating opening to push his body to the limit as electrical static emanates from his invisible dead father’s ghost.

This Hamlet moves better than he performs monologues, wondrously conveying panic and bewilderment as he scrambles on slippery surfaces, contorting his body into almost impossible positions. He runs like we do in nightmares.

A hive of frenetic activity

The opening signals the intention of this production to boldly mash up Shakespeare’s sacred scenes, taking a relatively dull description of some Trojan War swordplay related by the visiting players in Act 2 Scene 2 and using it to set the stage for the politics, warfare and intrigue ahead.

Nobody stands still for a moment as actors share lines, finish each other’s sentences and chant in unison – a charming moment as Family Polonius chime: “Neither a borrower or a lender be” as if it is their father’s catchphrase – a sustained pace through to the interval to the extent it plays like an episode of ‘24’. A few references to passing time might jar a little, but the audience is too gripped to notice, entranced in the incessant rain.

I recalled how much I disliked the opening half of the last ‘Hamlet’ I saw on stage, and as I returned to my seat for the resumption I was genuinely excited by the prospect that everybody was going to kill each other, instead of just willing them to do so to end the heartache.

Marvelously mashed and cleverly cut

An original score by 20-something electronic composer Mike Sheridan lends gravitas to the dark matter before us, and a relatively unobtrusive set lends itself well to a production that employs width to adeptly intertwine scenes to speed along the action. All in all, this version is just two hours long – some three days shorter than the Kenneth Branagh version.

Engel’s ingenious mash-ups continue as the likes of Horatio and a (dynamic for a change) Rosencrantz and Guildenstern take on extra functions – given the intrigue they bring, it’s shuddering to think Olivier cut them out all-together – and key scenes and characters are completely cut, including the brave omission of Yorick, the jester whose skull is HamletScenen’s logo.

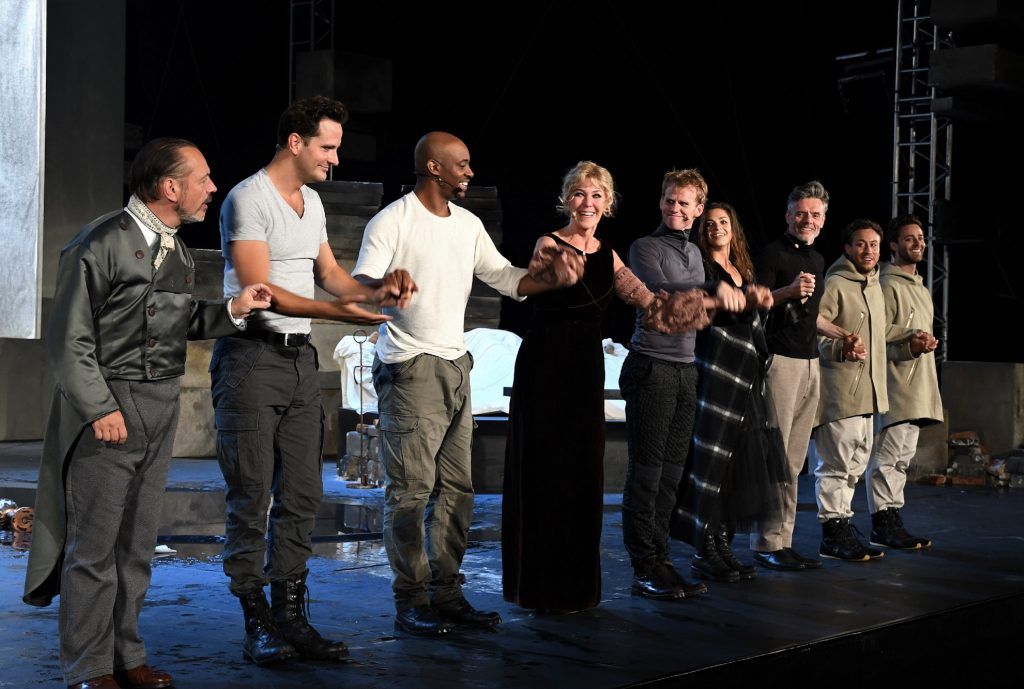

Overall, it’s difficult to signal out any of the nine performers for exclusive praise, as this was a solid ensemble with no chinks in the armour. Richard Clothier gave us a curveball Claudius who would have thrown Colombo off the scent with his understated reaction to the play within a play, and he was ably supported by Vivienne McKee as sister-come-wife Gertrude, who brought consummate inflection to her every line.

Night belonged to Ophelia

But if this was any actor’s play, it belonged to Natalie Madueño’s pitch-perfect performance as Ophelia. Two parts sassy, one part suicidal, while other roles were shrunk, hers was enlarged to depict the demise of a woman in a fiercely patriarchal society failed by all the men in her life.

Symbolically, the mid-stage puddle in which she hauntingly drowned never washed away, reminding us of the true tragedy at the heart of this tale.