An increasing number of people in Denmark have a so-called ‘Alien’s Passport’ recognising them as “stateless” because they can neither get a Danish passport, nor are eligible for a foreign one, reports DR.

While this is the case for many refugees and their reunified family members, tight Danish legislation means their children, born in Denmark, are too.

Many Danes affected

Zaniab Al-Ubboody, 22, was born in Viborg and went to school in Nivå and Helsingør, but rather than the usual red Danish passport, she has a grey ‘Fremmedpas’.

“I feel ashamed when I stand in line at the airport. Why do I have to have an Alien’s Passport when I was born here and my Danish friends have a red passport? It affects me a lot,” she told DR.

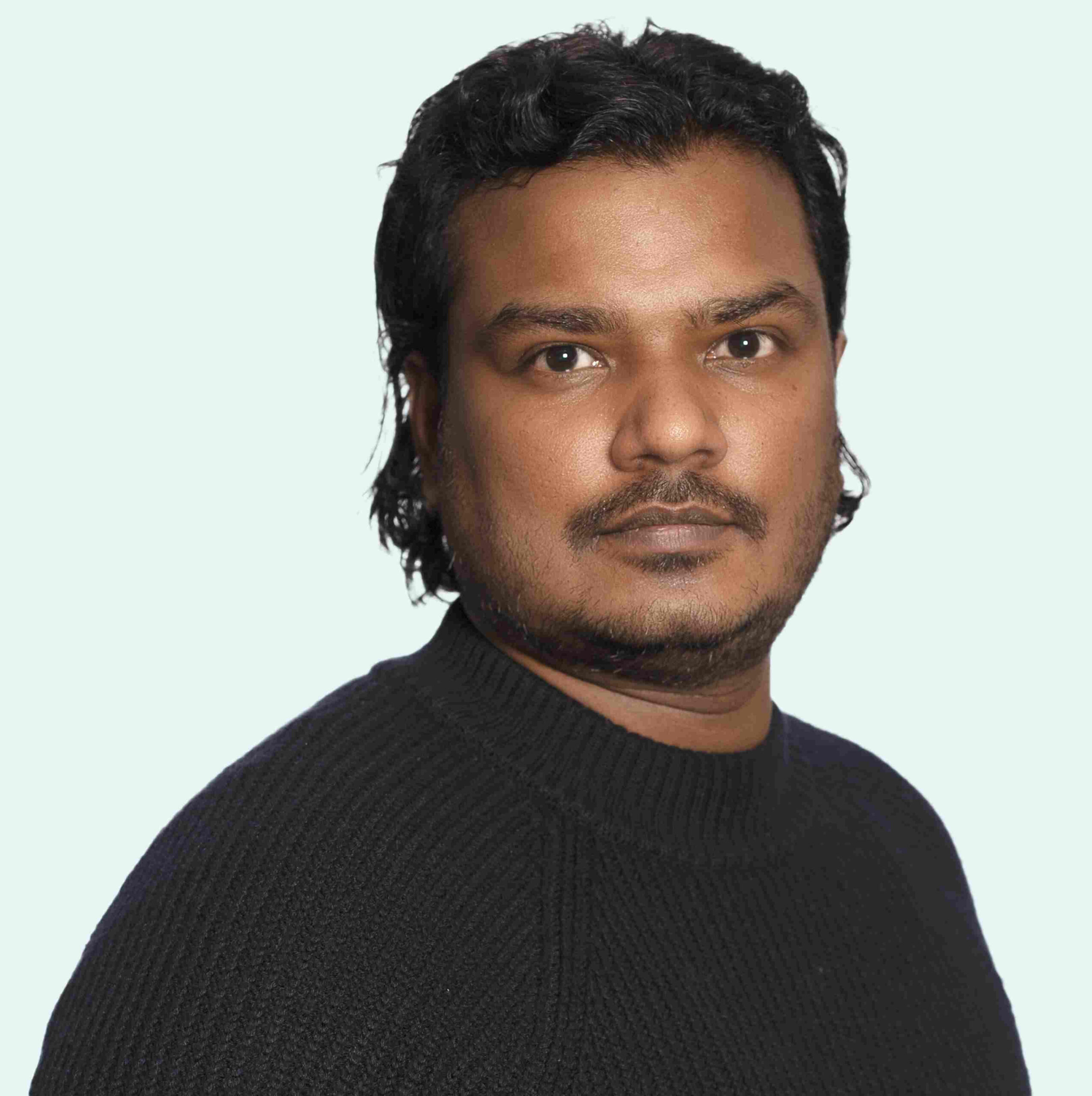

For Anders Maher, 23, who was born and raised in Frederiksberg and is studying medicine at the University of Copenhagen, it’s the same story.

“I was born and raised in Denmark. I think it’s absurd,” he says.

Why is this happening?

Between 2012 and 2014, some 8,000 to 9,000 people a year were issued an Alien’s Passport. In recent years, the figure has risen to around 14,000 annually, according to documents from the Danish Immigration Service.

The increase reflects a rise in foreign asylum-seekers, but also how it has become more difficult to become a Danish citizen thanks to amendments to the Citizenship Law, explains Jesper Lindholm, a professor at the Department of Law at Aalborg University.

Opposition on the right

Dansk Folkeparti asserts that the rising number of Alien’s Passports is the result of an immigration policy that is too relaxed.

“They are foreigners if their parents have not taken root in Denmark and do not have a right to be here. Denmark is not their home and cannot be. They have to go home to the country where their parents are from, even if they aren’t familiar with it,” contends DF spokesperson Marie Krarup.

Ny Borgerlige wants refugees and their children sent home faster and citizen rules tightened even more. “If people don’t live up to the requirements, it’s fine if they have a foreign passport for years,” according to spokesperson Mette Thiesen.

“I don’t see what the problem is. You can have a good life in Denmark without being a Danish citizen. Denmark throws around far too much citizenship. It should be for the very, very few,” she added.

Support on the left

However, Radikale and Enhedslisten agree it has become too difficult to achieve citizenship.

“It’s a democratic disgrace that we have a growing number of citizens who have legal and permanent residence, but not full rights,” contended Enhedslisten’s Peder Hvelplund.

“Alien’s Passports are an eternal reminder that you are not a full member of society.”

Tesfaye won’t budge on the rules

Claiming to understand the frustration, the immigration and integration minister, Mattias Tesfaye, said: “If you were born and raised in Denmark and are active in society, then I also think that you should become a Danish citizen.”

But in 2021, he and incumbent party Socialdemokratiet stonewalled a proposal by Radikale that would have made it easier for young people born and raised in Denmark to become citizens.

“We previously had more lenient rules where people who did not speak Danish got citizenship. It’s good we have tightened the rules. I will only encourage people to apply if they feel like Danish citizens. Several thousand are accepted every year, and I’m happy about that,” said Tesfaye.

A lengthy process

The current citizenship process takes several years. Many young people can expect to wait until their late 20s to become Danish citizens, according to Kristian Kriegbaum Jensen, a professor specialising in politics and administration at Aalborg University.

“One of the rules is that young people must have worked full-time for three and a half years out of four to even be able to apply for citizenship – which is next to impossible while studying,” he explained.

On average, a citizenship application took 16 months in 2020. Applicants need to pass a written test and be approved via a constitutional ceremony in their municipality.

Still, according to many right-wing voices in Parliament, it’s too lenient.

“We wanted the rules tightened even more, and a limit imposed on how many non-European and Nordic citizens can get a Danish passport every year,” said Marcus Knuth of Konservative, who encourages young people with Alien’s Passports to be grateful and to “stop complaining”.