In part one of this story, we saw how the Danish grandson of the Viking leader Harald Bluetooth came to rule over a North Sea empire and ushered in a period of tranquillity and trade.

At the start of his rule Cnut had been ruthless, putting to death many a nobleman and imposing harsh taxes on the populace to pay the soldiers of his invading army. But he soon began to mellow, settling into his role as king of England and Denmark, and turning his efforts towards becoming a more benign ruler.

Charming the church

Cnut was acutely aware that others saw him as a Viking and a pagan. The bishop of Chartres, in France, called him the “pagan prince”. This was no good for Cnut: the church was the most powerful institution of the Middle Ages and he needed to be on the right side of it. So, after his visit to the Holy Roman Emperor in Rome, the young monarch set out on a charm offensive in order to convince people of his impeccable Christian credentials.

Using the considerable wealth he had amassed using the Danegeld regimen, he was able to purchase holy relics and commission great works of art, which he showered liberally on the religious institutions of England.

The English were much in thrall to Christianity at the time and aggrieved at all the damage done to churches and cathedrals by Viking raiders over the years. Cnut set out to make reparations for this, pouring money into restoration efforts and using his favour with Rome to grant English clergymen concessions.

It was the Benedictine monastery Hyde Abbey at Winchester on the south coast that Cnut favoured the most, giving it a gift of a giant gold cross of untold opulence. Indeed, Winchester became Cnut’s favoured place of residence – he had never been keen on London since he laid siege to the city.

Another place favoured by Cnut, not all that far from Winchester, was a small village on a tidal islet of Chichester Harbour, where he had himself a palace built. Some historians believe that Cnut favoured the village of Bosham because it was where he first landed during his invasion of England.

Misreported by the courtiers

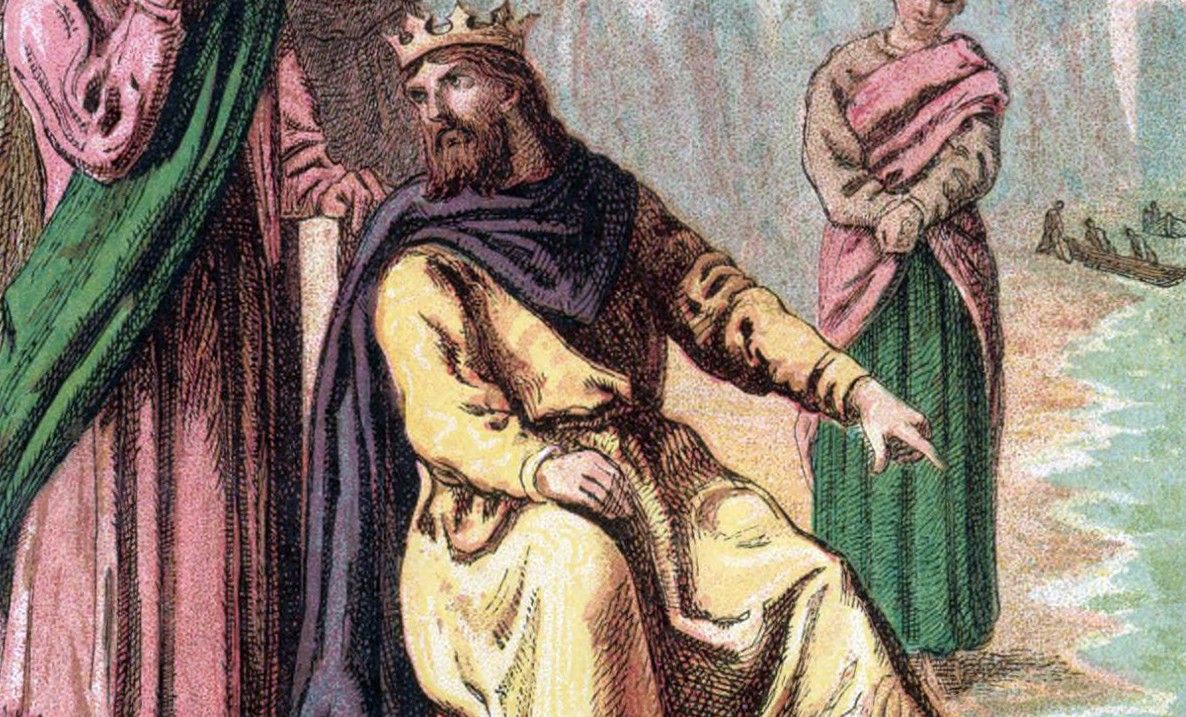

Whatever the reason, it was here that he was said to have placed his throne on the tidal mudflats and with a raised palm and the words “Go back sea!” ordered the waters from rising about his royal ankles.

The common interpretation of this apparent show of egoism is interpreted as a display of self-delusional omnipotence, but the truth of the matter is that Cnut, tired of all the expectations heaped upon him, was merely using slapstick humour to prove to his subjects that even he possessed limited powers.

It’s not hard to imagine the scene, with Cnut wearing his crown and robes and displaying a very Danish sense of humour as he made an ass of himself in front of the incredulous onlookers who had demanded so much of him. When his feet and robes became wet, Cnut was said to have leapt up and cried: “Let all men know henceforth that the power of kings is an empty and foolish thing,” and was said never to have worn his crown again, instead placing it on a statue of the crucified Jesus.

A thousand years later, patrons of the Anchor Bleau pub park their cars outside on the mud flats, only to return hours later to discover the sea still refuses to stop rising at the spot where Cnut performed his play-acting.

But Bosham wasn’t all fun and games for Cnut. He had a young daughter who fell into the mill stream and drowned. Today the mill stream is still there and the bones of Cnut’s young daughter are interred inside the small but perfectly formed Norman church nearby. Also said to be buried in the churchyard are the bones of Harald Godwinson, the last king of England prior to the Norman conquest.

Popular with the people

Cnut enjoyed huge popularity among the English people and would welcome visitors, including the common people, into his court. One day a travelling Icelandic minstrel turned up and, on meeting Cnut, composed the following poem: “To Cnut the Dane I tune my lay; English and Irish own his sway, And many an island in the sea; So let us sing his praise that he be known of men in every land To where heaven’s lofty pillars stand.”

The king was so flattered by the ditty that he took off his cap and filled it with silver coins as a gift to the Icelander, who was of noble birth. But, passing it above the heads of the crowd that thronged his court, the cap was dropped and the silver coins were spilled on to the floor, much to the delight of the poor people, who grabbed at and pocketed them. “Let them have it,” Cnut laughed. “They have greater need for it than you.”

Life ends at 40

But Cnut was not to enjoy a long reign. He died, aged 40, from some type of common malady and was interred in a reliquary at Winchester, where his bones still lie.

His two sons, by different women, lacked their father’s steadfastness and leadership skills and, following a messy period of political manoeuvring with Scandinavia, both died without leaving heirs after only a few short years.

READ MORE: Mystery of Danish king deaths fosters new theory

The dynasty of the Danes was at an end, with power in England passing back into Anglo Saxon hands. Thirty-one years later, in 1066, the aforementioned King Harald was defeated by William the Bastard at the Battle of Hastings and the rest, as they say, is history.

Although his reign was brief, the legacy of King Cnut was considerable. He was the first king who had managed to unite not just the warring elements of England, but also to ally the country with Scandinavia. Under his stewardship, the arts flourished and people enjoyed a period of peace for the first time, literally, in ages. The concept of individual justice was introduced, and trade boomed.

And the story of his failed wave-stopping exploits is still remembered today. In November 2010, Radiohead singer Thom Yorke arranged for 2,000 climate change demonstrators in Brighton to use their bodies to create a giant image of the Danish king attempting to turn back the tide as a metaphor for political inaction on the threat posed by rising sea levels.

And so, it seems, the story of the man with the name one mustn’t miss-spell lives on.