The fantasy horror writer H.P. Lovecraft used him as the model for his creepy character Olaus Wormius, who translated the notorious ‘Grimoire the Necronomicon’ from Arabic into Latin, thus inspiring ‘Cthulhu Cult’ copycat novels and video games for centuries to come. But the real-life Olaus Wormius was the Latin translation for one Ole Worm, the learned title Denmark’s first antiquarian used himself.

Renaissance man Ole Worm (1558-1654) was a physician from Aarhus who was sent by his wealthy family to study in Germany aged 13, and who after much time spent in the various universities of Europe finally received his last degree in Copenhagen aged 29. His duties as a doctor ranged from being assigned personal physician to King Christian IV, to being one of the few people to remain in Copenhagen during the Black Death in order to minister to the plague’s victims.

A specialised embryologist, the ‘Wormian’ bones, small bones that fill the gaps in the cranial sutures, were named after him. Moving away from science, he was fascinated by the runic alphabet of Nordic history, translating many runic sagas and collecting huge amounts of early Scandinavian literature.

Arch-archivist

But it was for his work as an archivist and antiquarian that we remember him. Perhaps the real reason why most of what we now know as history began with the Renaissance period is that this era heralded the birth of the ego. This egoistic drive towards immortality amongst kings, scientists and scholars of the 14th and 15th centuries resulted in huge amounts of artefacts, portraits and documents saved for future generations. Like King Christian and Tycho Brahe, Ole Worm desperately wanted to be remembered for something brilliant.

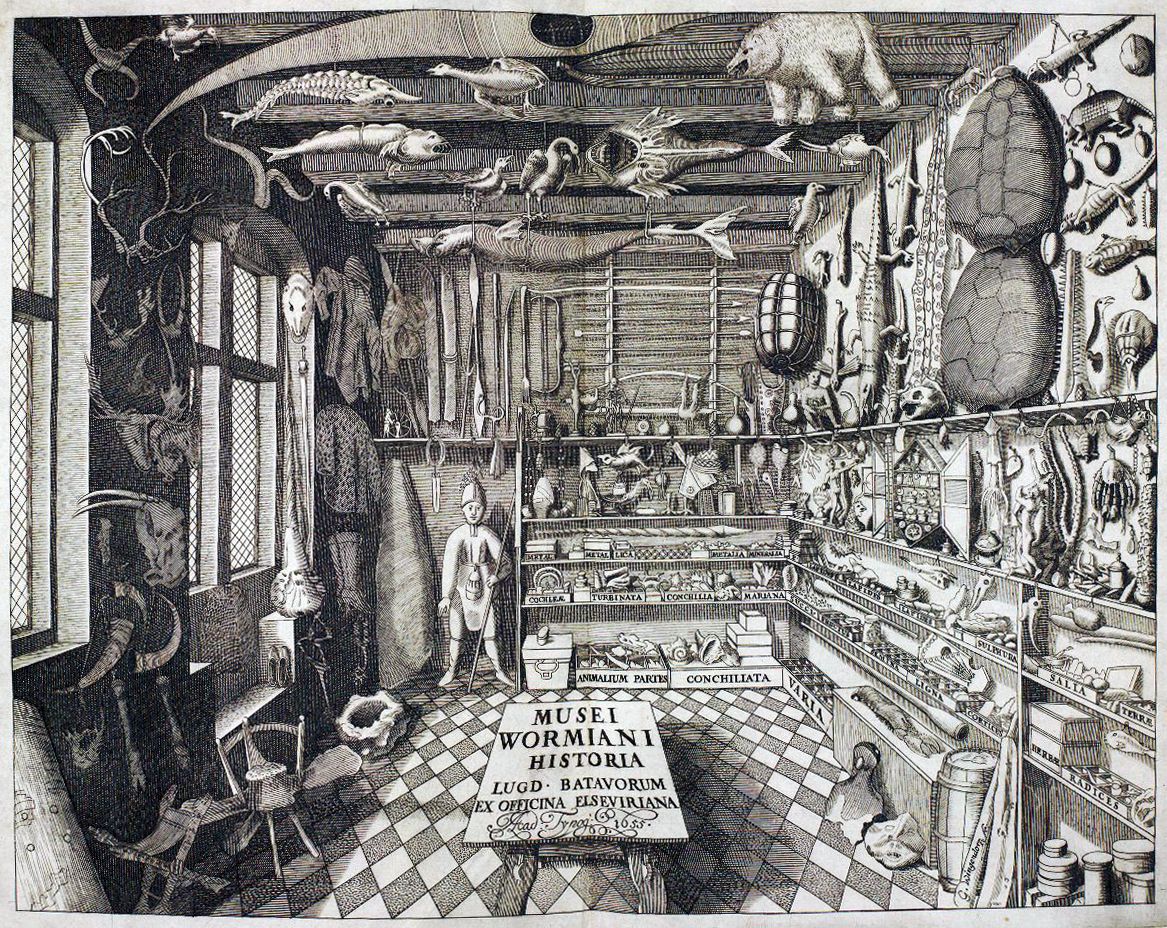

His almost obsessive desire to collect and catalogue just about everything he came across has meant that many of his findings can still be seen today. His ‘Museum Wormanium’, which was stored in rows upon dusty rows in a building on ‘Skidenstræde’ (now known as Krystalgade, the street where Copenhagen’s central library now stands), was Denmark’s first ever museum.

The Wormanium was filled with stuffed animals, cultural curios from Worm’s extensive travels to newly discovered lands, and fossils, which he never tired of. The select few who got the chance to view his artefacts back in 17th century Denmark must have marvelled over the stuffed polar bear, the tribal weapons, the dried exotic fish and the turtle shells.

Unicorns debunked

His scientific studies emphasise the fascinating transition which the Renaissance straddled: from a world shaped by the belief in magic to one governed by modern, rational analysis. One such empirical investigation provided convincing evidence that lemmings were in fact rodents and not, as was the general belief at the time, spontaneously generated by the air. Another was his detailed drawing of a bird of paradise, which proved once and for all that they did in fact have feet like normal birds.

It was his study into unicorns though that went furthest in its pursuit of the truth. He determined that unicorns did not exist and that those horns purported to be from the unicorn were actually narwhal tusks. Still, he couldn’t help but be carried along by the notion that unicorn horns contained an antidote to poison, and with this in mind he carried out primitive experiments where he poisoned pets and then served them ground-up narwhal tusk. He reported that they did recover, suggesting that this poisoning wasn’t quite so efficient.

Ole Worm died of bladder disease in 1654. His extensive collection was then purchased by King Frederik III, who used it for the basis of ‘The Royal Kunsthammer’, a fascinating collection of historical artefacts which can still be seen today. Most of what remains of Worm’s antiquaries is on view at the zoological museum in Copenhagen.