According to the Global Peace Index, Denmark has been among the top 5 safest countries in the world for 16 years. In media reports, institutional rankings and the popular imagination, Denmark is widely acknowledged as one of the happiest countries.

Safe-haven illusion

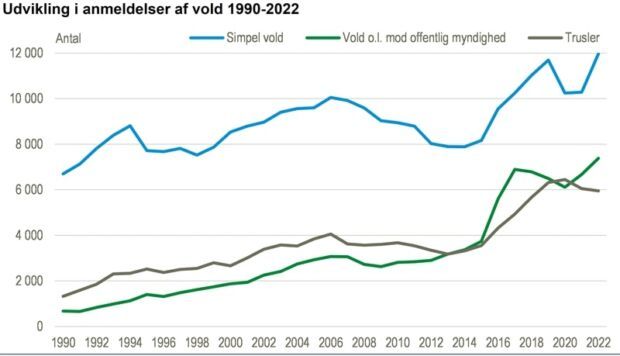

But in 2022, 31,374 cases of violence were reported in Denmark – the highest number since 1990, when Statistics Denmark‘s records began.

In fact, after declining during the pandemic, the number of cases of reported violence increased by 16 percent from 2021 to 2022.

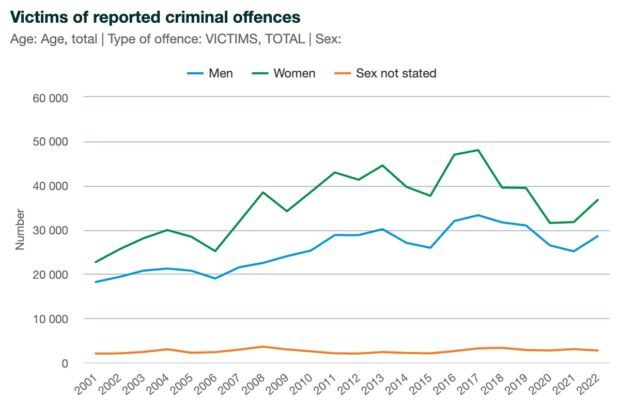

In step with this, the number of reported victims increased by 14 percent between 2021 in 2022, ending a five-year downward trend.

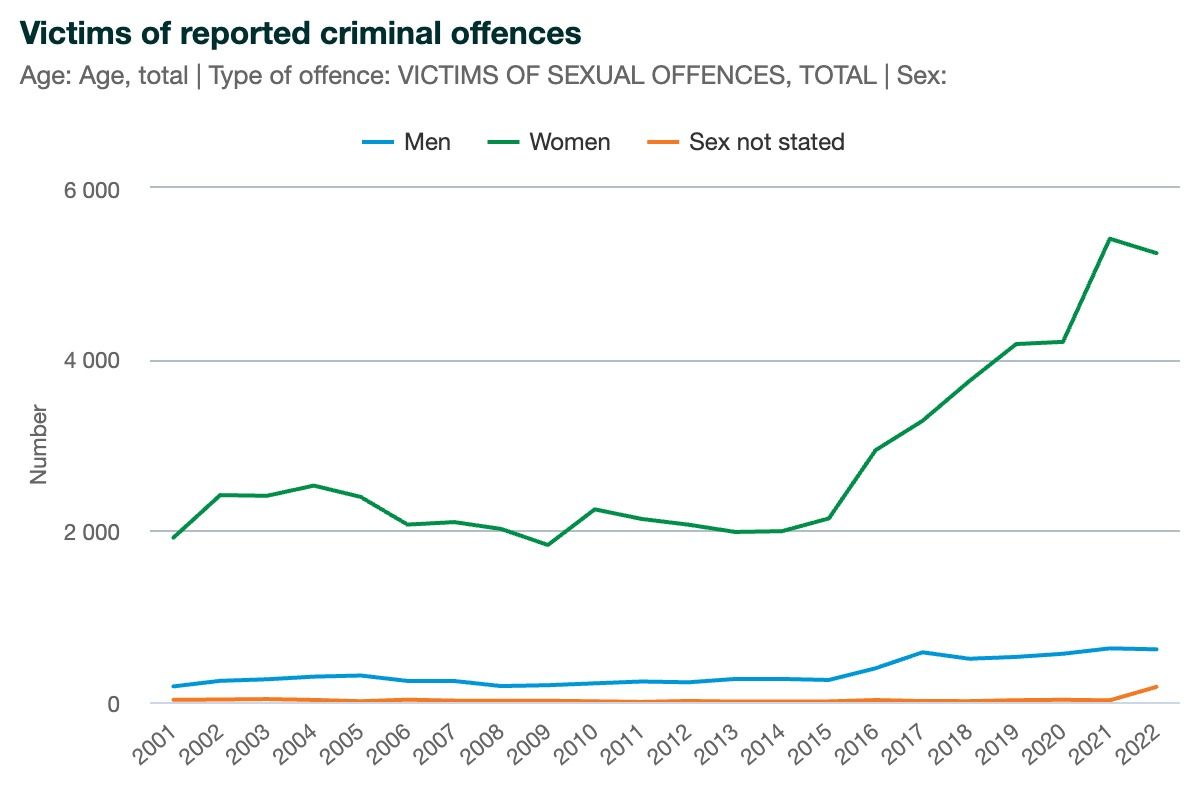

The proportion of cases in which there are female victims has been higher than male since the earliest record of this metric in 2001.

In 2022, there was a pronounced disparity in the gender split of the reported victims: 54 percent were female, while 41 percent were male.

The gap is especially large regarding sexual offences. Female victims overwhelmingly outnumber males, and the difference has grown since 2016.

Violence in the news

Recently, high-profile cases of violence in which the victim or victims are female have appeared in Danish headlines.

In February 2022, 22-year-old Mia Skadhauge Stevn’s death shocked Denmark. After Stevn went missing after a night out with friends, her dismembered body was discovered with signs of attempted rape. A stranger to Stevn, 36-year-old Thomas Thomson, was convicted of her murder.

The brutal incident is one of the most shocking murders in modern Danish history.

This April, a 13-year-old girl was abducted and raped on her way home by a 32-year-old man. The perpetrator was sentenced to prison, and charged additionally with kidnapping, raping, and killing 17-year-old Emilie Meng in 2016. Moreover, he is accused of attempted rape and abduction of a 15-year-old girl in Sorø in November 2022.

Grades of violence against women

While extreme cases of kidnapping or murder occur relatively rarely, other forms of sexual, physical or verbal violence against women are commonplace.

Unexplained animosity, verbal aggression, and physical assaults also constitute violence. When these incidents go unreported by the media or the police, they often leave an indelible mark on the lives of the victims.

In the following accounts of everyday violence, shared by women living in Denmark, names have been changed to protect their anonymity.

In 2018, while riding her bike home one evening in Copenhagen, Ves was touched on the breast by a passing cyclist.

Since then, Ves describes being wary of cyclists, feeling uncomfortable and alert if they come too close.

Last month at a Copenhagen metro station, a teenager aggressively stared at Jane, eventually elbowing her. Jane describes that, panicked and stumbling, she fled the scene as a crowd watched, but no one intervened. The incident continues to affect Jane, making her uneasy every time she goes the station.

“It destroys every confidence I have that someone will step in if something goes wrong,” Jane said.

In Aarhus, Martha experienced harassment on a bus when a man touched her thigh and another girl’s breast. Martha, disappointed by the lack of intervention, compared the situation with what she would expect from her home country, Poland.

“If it had happened in Poland, witnesses would have called the police and strong men would have come up to protect us. But here, people simply don’t care,” Martha said.

Martha asked the other girl if she wanted to report to the police, but she refused on the basis that she did not expect the authorities would do anything.

The next day, Martha went to the police, where she was told that it did not qualify as an assault.

Struggles and solutions

In a study of 500 cases of reported public violence in Copenhagen that took place between 2010 and 2012, 72 percent involved a single alcohol-intoxicated perpetrator who, in 67 percent of those cases, was a stranger to the victim.

In broader violence studies, it is widely acknowledged that women disproportionally suffer from violence and conflicts.

And according to Khanh Overgaard, an analyst at South Jutland Police, “women are more harassed but more unreported.”

In the 2023 Women, Peace and Security Index, Denmark is ranked the top country of 177 in which to be a woman.

In 13 indicators, Denmark scores the best or among the best group in 12 of them. However, its lowest score is for ‘women’s perceptions of community safety’ – in which 78 percent of women aged 15 years and older report that they “feel safe walking alone at night in the city or area where you live.”

In this metric, Singapore takes the top spot with 94 percent.

“When rights for women are achieved or expanded, we might think we’ve solved the problem. But gender inequality is persistent and historical. there are struggles and inequalities we may not able to see even after the achievement or the expansion of some rights,” says Pablo Selaya, an economist at the University of Copenhagen who studies gender inequality.

How can violence against women be mitigated?

Khanh suggests that alcohol control may be a key factor in decreasing public violence.

Compared to other Nordic countries, Denmark provides easier access to alcohol.

Firstly, the legal age for purchasing beer and wine is 16, lower than 18 – 20 in other Nordic countries. Secondly, most stores are allowed to sell beverages with an alcohol volume of up to 16.5 percent ABV, while in Finland, Norway and Sweden, beverages with an ABV above 3.5 to 5.5 percent are only available in government-owned alcohol retailers.

“We should make alcohol more expensive and inconvenient to get, thus decreasing the accessibility to alcohol,” Khanh argues.

Bystander intervention

Bystander intervention has been proved effective in countering violence. Researchers argue that bystanders could be an available crime preventive resource, especially in crowded night-time settings.

Camilla Bank Friis, a postdoc at the Department of Sociology, University of Copenhagen researching crime, says “the point here is for victims to see other people as resources to seek help. And when bystanders intervene, it’s usually successful. Also, the risks for interveners to be victimized are relatively small.”

In a cross-national study of 219 public conflicts in South Africa, the Netherlands and the UK, 9 out of 10 conflicts were disrupted by bystander intervention. This type of intervention can informally regulate public violence before the police arrive.

Do interveners risk their own personal safety?

A study of bystander behavior in 69 cases of public violence in Copenhagen between 2010 and 2012 found that interveners do expose themselves to some risks – but that the majority are not subsequently victimized during the intervention. Meanwhile, the general risk to the intervener was classed at a “low degree of severity”.

“People should only intervene when they feel ok to do so,” Friis emphasizes.