Whether it’s via the increasing airplay of Congolese urban funk or the wide popularity of Afro-beat EDM tracks, regional music created by artists living outside of Europe and USA is finally gaining mainstream recognition. However, their success is a fairly new phenomenon.

Back in 1987, a group of British enthusiasts created the genre of ‘world music’ in an attempt to bring greater profits and recognition to performers from across Africa, Asia and South America, but experienced producer Carolina Vallejo contends that the catch-all term has served to limit the commercial viability of performing artists whose music it’s come to characterise.

A creative education

Born in Greece, Vallejo relocated to Denmark at the age of three. Spending her youth in Copenhagen, she chose to attend an art school in Barcelona during her 20s. Later returning to the Danish capital to study for a further degree in concept design and development, it was here Vallejo took her first earnest steps into the music industry.

“I knew a jazz drummer called Jonas Johansen who was playing with the Danish Radio Big Band,” Vallejo recalled to CPH POST. “He asked me to book concerts for his trio with Steve Swallow and Hans Ulrik.”

Subsequently organising tours across Denmark and Spain, her skills in organisation, promotion and art direction were increasingly sought by a range of different musicians.

“Since I was interested in the whole thing, I would never just do the booking,” recounted Vallejo. “I would also help to do the album covers, take band photos – essentially handle their whole production.”

An unlikely meeting

While continuing to promote and manage local bands, Vallejo began to exhibit her artwork around the world whilst expanding her production at her workshop and gallery, Aurum. And then a chance encounter with a little known Kenyan musician in 2008 reorientated her career to encompass an even more global focus.

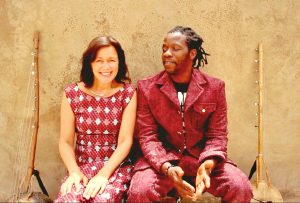

“I went to WOMEX [World Music Expo] in 2008 in Seville, Spain, and that’s where I met one of my most successful artists: Makadem,” she remembered.

“I made friends with him and his sound engineer, and I was saying that I had never been to Kenya – or Africa for that matter – and he said: ‘Oh, we can make that happen’.”

Establishing relations through Makadem with communities in Kenya, Vallejo was granted state support to create a substantial art piece using local methods and materials, which was later featured at the Karen Blixen Museum in Rungstedlund.

“I went to the Masai Mara and worked with people there to develop the pieces,” she recalled fondly. “They are exact copies of the Danish crown jewels, but made with pearls and leather using local techniques.”

It was here, while travelling in the country, that she met Makadem for a second time, latterly agreeing to manage and produce his music through her newly-formed production company.

An inclusive worldview

Over the following years, Vallejo grew her business to comprise a wide variety of international acts. Nevertheless, she argues that the success of her brand has been based on disavowing the typology of world music when promoting her performing artists.

“I understand, completely, why they invented the term [world music] as they were missing a category to put music in that was not pop, rock or jazz,” contended Vallejo. “But it’s too wide; it’s too big, and somehow it gives a sense that it’s not at the same level as other forms of music.”

Vallejo’s determination to change how foreign musicians were being treated won her Celebrate Africa’s ‘Best African Promoter in Denmark’ award in 2011. This, she attests, was given due to the concert invitations she extended to Denmark’s African-expat music fans and her insistence that international performers be properly financially rewarded.

“Normally here, so-called ‘world music’ would be cheap – you might pay 50 kroner [for entry to a concert],” Vallejo remonstrated. “But I would put on concerts where the ticket price was 150 kroner because I wanted people to know that this music is really valuable, and funnily enough, we did have sold out venues.”

Making it in Mali

In the past, Vallejo has won awards for her production work on the albums of Guinean artist Sekou Kouyate and Makadem. Furthermore, her music label is set for a landmark year in 2018, with three of its acts – Harouna Samake (Mali), Yuliesky Gonzalez (Cuba) and John Mutombo (Congo) – releasing full-length records. Yet Vallejo’s daily work remains rooted in an immersive, hands-on approach, viewed in her recent decision to record with Samake in his home city of Bamako, Mali.

“Though I planned to stay one week, I ended up staying there for two months to produce the full album,” Vallejo coolly remarked. “And luckily, I received support for this album from Statens Kunstfond [the Danish Arts Foundation].”

“We worked on the album in his studio in Bamako on the rooftop of the home where he lives,” she continued. “I also later filmed and directed his music videos, took [album] photos and designed his stage clothes.”

In 2012, Mali witnessed two violent uprising. Led by various hard-line groups, music was briefly outlawed in the north of the country. A peace accord was struck between the militias in 2015, and Vallejo stresses that her recent travel experience in Mali was entirely incident-free. However, like many musicians, Samake’s newly-released music considers the prevailing social status quo.

“Harouna’s music is a mix of styles inspired by groovy jazz and blues,” explained Vallejo.

“But the lyrics, sung in his native Bambara with some English and French, are about society, and he talks about issues like immigration, poverty and wealth, respect between men and women, and human rights.”