Carl August Lorentzen may not be the originator of the line “Where there’s a will, there’s a way,” but for many in this country, his name will forever be linked to the immortal phrase.

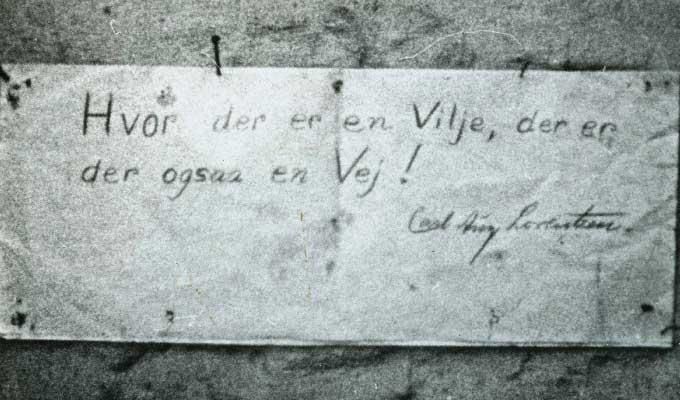

The habitual robber made front-page news over Christmas 1949, after his colourful escape from Horsens State Prison in Jutland in the early hours of December 23. When guards went to check his cell that morning, they found it empty – save for a hole in the wall and a note with the famous quote written on it.

Industrious Lorentzen had spent the last eight months digging his way to freedom, first making a hole and then an 18-metre tunnel from an adjacent room to his cell down to the basement of the prison, where the authorities kept those inmates they deemed the highest security risk. The dirt and earth he couldn’t hide in the room he placed in socks, which he then attached to his belt and carried up the stairs to the loft.

Horsens as Troy

If it all sounds like something from ‘The Great Escape’, it should come as no surprise to hear that Lorentzen had read ‘The Wooden Horse’, a book about a daring POW escape made from the same camp featured in the WW II classic, from cover to cover shortly after its publication earlier in 1949.

After escaping, he enjoyed a mere six days of liberty before being discovered hiding out at a farm just six kilometres south of Horsens. Being hungry, he had broken into the farm’s kitchen, where he was caught by the owner.

After his short-lived flight to freedom, Lorentzen spent the rest of his days at Horsens State Prison, right up until his death in 1958 aged 63. He spent much of his time producing models, wood carvings and drawings – the latter of which he displayed quite a talent for.

The museum at Horsens State Prison (which is available to visit by appointment only) has saved hundreds of these pastel drawings, many of which look back wistfully on Lorentzen’s lonely, poverty-stricken childhood in Frederiksberg in the early 1900s.

Prevailingly in prison

Lorentzen was a career criminal who began stealing young. At the age of 14, his training as a waiter brought him into contact with the smuggling and stolen goods underworld in Nyhavn.

He immigrated to Canada a little later, but upon returning at the age of 19, his career as a burglar moved up to the big time. He seemed to take pride in doing his job well, and he would often break into one of the era’s new, high-security safes not to take any money – which he left untouched – but simply to place a note inside reading “He could”.

Lorentzen appeared to have one failing as a thief: he kept getting caught. From the age of 19 up until his death at Horsens State Prison aged 62, he spent a grand total of five years out of jail. If he hadn’t been so obsessed with making a name for himself, perhaps he could have kept himself out of the glare of the police flashlight.

Lorentzen had attempted to break out of jail eight times before his great escape, but never as flamboyantly as he did that night just before Christmas in 1949. Finally, he had found that fame he so desperately sought.