In yet another example of the extraordinarily poor timing exhibited by the industry, the late celebrated French designer Yves Saint Laurent has not one but two releases based on his life and work released within the same year. Ironically this echoes the 2008-09 release of two films based on that other French fashion legend, Coco Chanel (three, if you count the Lifetime min-series, although you probably shouldn’t).

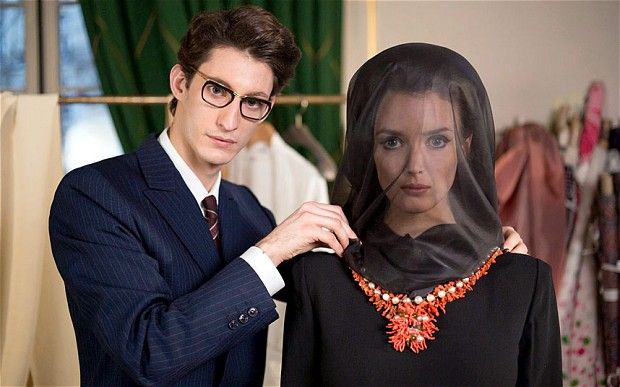

Different model fortunately

Whereas Jalil Lespert’s officially endorsed biopic, Yves Saint Laurent, focused on the chronology of the designer’s life – his early years in Algiers, his meteoric rise through the ranks at the House Of Dior (YSL was famously the lead designer by the age of 21) and, alongside his business partner and lifelong lover Pierre Bergé, the formation of his own brand – this is primarily concerned with the relationship between YSL and Bergé.

The latter’s character provides a voiceover throughout, which posits us at a distance from YSL himself, leaving us to observe rather than experience first-hand.

A consummate collection

Enter Saint Laurent. This version, directed by Bertrand Bonello (House of Pleasures), dispenses with the formative years and begins in 1967, when the YSL brand is at the height of its power, shortly following the creation of the famed Mondrian dress.

Bonello’s film is concerned only with subjectivity. And that is not limited to YSL himself, but instead offers a broad, in-depth study of his entire world from several perspectives. We get the sobbing seamstress who has to restart one collection four times due to YSL’s perfectionism;

Berge’s (Renier) shrewd business dealings with frustrated American distributors; and of course YSL’s distractions – namely his fixation with his mother (whom, the film suggests, is his initial inspiration and a lifelong muse) and his destructive hedonistic affair with the Karl Lagerfield model Jacques de Bascher (a brilliantly dangerous Garrel).

Obsessive stitching

Most refreshingly though, Bonello eschews the usual formula for the artist’s biopic, showing genuine reverence for ‘the creative process’, giving equal attention to YSL’s designs and the craft employed in realising them, as he does to YSL’s turbulent love-life.

The level of detail here is obsessive, to the point the viewer receives a fascinating education on how a fashion house really functions day-to-day. Bonello strives to communicate an overwhelmingly visceral, sensory excitement – so that one gets the impression of having felt the fabric, done the drugs and drank in the decade.

Superior design

Gaspard Ulliel (previously seen in title role of Hannibal Rising) wears the iconic hair and glasses, rather than the other way around, and the support cast are outstanding. Visually, the film is flawless – of particular note is Katia Wyszkop’s exquisite production design, which contrasts the clinical whites inside YSL’s studio with a Paris of blood crimsons and onyx blacks beyond it.

In short, if you’re going to see one film about YSL this year, make it Bonello’s. Both films struggle with an estranged, even chilly protagonist, but Lespert’s approach, being all narrative bones, was weighed down by a duty to a chronology that Bonello’s episodic study wisely pays scant attention to. Overlong and unwieldy it may be, but Bonello clothes his film in all the beautiful flesh that Lespert’s bones so sorely lacked.