Dir: Randy Barbato & Fenton Bailey; US biodoc, 2016, 108 mins; featuring Debbie Harry, Fran Lebowitz, Brooke Shields

Premiered june 16

Playing Vester Vov Vov, Gloria & Valby Kino

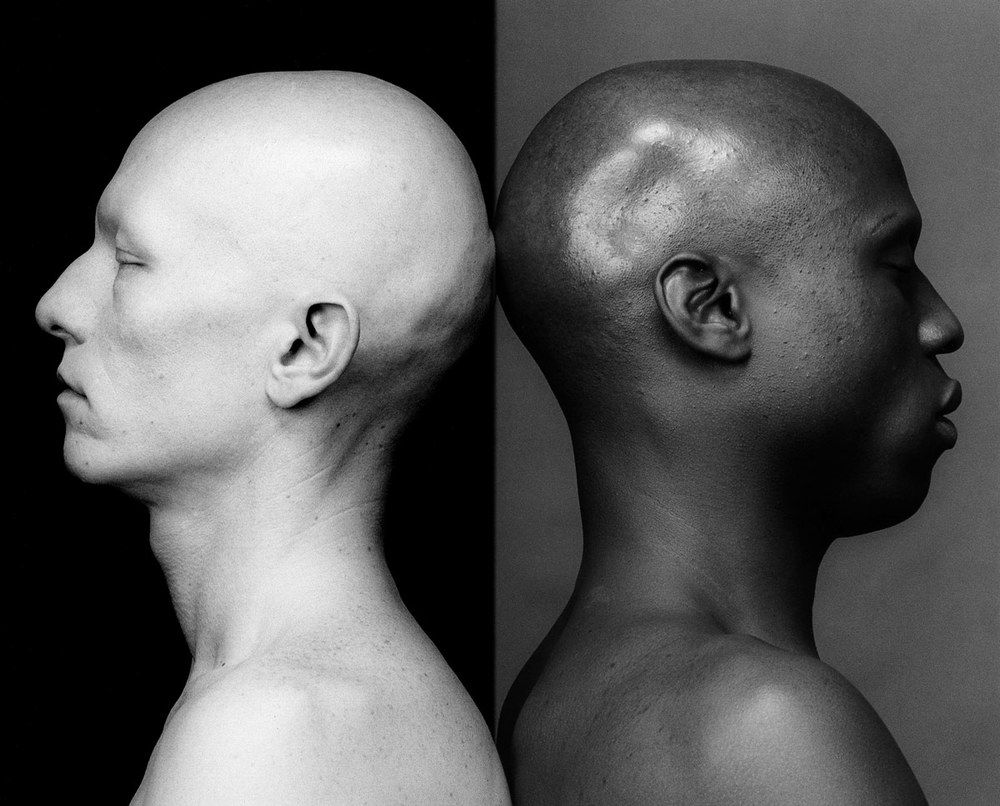

The greatest triumph of Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures is that it delivers a layered portrait which, in accordance with the documentarists’ repeated assertion of duality running throughout photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s life and work, describes a man who was a ruthless force of nature in regards to his career and yet capable of great vulnerability in his relationships.

This becomes considerably more complex territory when one considers that these two areas were not in competition with each other but rather inseparably blurred for Mapplethorpe.

Artist and provocateur

Mapplethorpe was a notorious figure in modern art throughout the 1980s and especially in the early ‘90s following his death from an AIDS-related illness. His photography was a combustible topic throughout America and beyond, with many major media outlets dubbing his work as sick and depraved.

The images still have the power to shock today, but few would dispute their significance. As an art form, Mapplethorpe elevated photography to the same level as painting and started a lasting debate about censorship, ultimately progressing the dialogue between porn and art.

Lover and user

If a dramatisation were made of Mapplethorpe’s life (one is apparently pending, starring Dr Who’s Matt Smith), it would inevitably simplify his approach to work, preferring to focus firstly on his relationship with singer-songwriter Patti Smith and ultimately African-American model Milton Moore, whose penis gained notoriety in one of Mapplethorpe’s most iconic images, ‘Man in Polyester Suit’.

Mapplethorpe was apparently devastated by his split with Milton, becoming inconsolable for weeks. In a fiction film, this point might be laboured over, but here it is felt quickly and sharply; the event is afforded a context by the cumulative effect of many first-hand accounts from and about Mapplethorpe’s litany of lovers and collaborators.

We learn it was rare for Mapplethorpe to love altruistically – often his choice of lover was motivated by money. On the curator Sam Wagstaff, who bank-rolled much of Mapplethorpe’s early career, the artist himself is quoted as saying that were it not for Wagstaff’s money, they might never have been together.

Enigmas and ironies

To further credit to the filmmakers, they don’t allow these findings to give us easy conclusions on Mapplethorpe’s character. Instead we’re given a fully-rounded sense of the human being, so that we feel we’ve grasped something more profound than a handful of details – we’re allowed to neither love nor hate the man, we simply get to know him in a way that stays with us beyond the credit roll.

Bookending this comprehensive chronology of the artist’s life, directors Bailey and Barbato have used the curatorial preparations for an upcoming pair of exhibitions curated by the Getty Museum and LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art) functioning as one show over two venues. This won’t be the first time Mapplethorpe’s work has been split in such a way, as Sam Wagstaff originally had great success with the same approach in New York.

Not only does this further support the dual nature of the man’s art and life, but these bookends come in stark, almost comedic contrast when juxtaposed against Mapplethorpe’s untamed life of sexual and artistic excess: the besuited curators stand in vast, sterile, white storage rooms, clustering around these wild images, all the time gushing their vapid analyses – quite unaware of the ironic distance between their world and Robert Mapplethorpe’s.