Today’s media is dominated by images of refugee camps being cleared and documentaries about people trying to flee war-zones, repressive governments – or just abject poverty – in order to make better lives for themselves and their families. At the same time, the rhetoric of the tabloid press has been ratcheted up to fever-pitch against these unfortunate individuals.

READ MORE: Exposing the poverty in New York’s underbelly

In this context, it is extremely timely that Kunstforening Gl Strand has just opened a substantial exhibition of the photographs of the pioneering Danish social commentator, Jacob A Riis. If nothing else, the exhibition emphasises the fact that one good man with a mission really can change things for the better by appealing to the social conscience of decent people.

Riis is probably better known in his adopted country of the United States than he is in Denmark. Born in Ribe in 1849, he emigrated in 1870 – in search of a better life. He was trained as a carpenter, but soon took up writing and journalism and worked as a police reporter for the New York Tribune and Evening Sun for 23 years. Nicknamed ‘the Dutchman’ by his colleagues because of his foreign accent, Riis was a bit of an outsider. His office in Mulberry Street was opposite the police station and right in the middle of some of the worst slums in New York.

A photographer of sorts

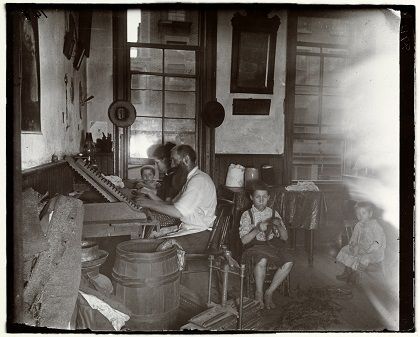

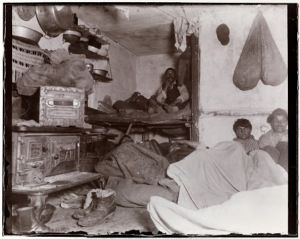

As Riis himself put it, he was only “a photographer after a fashion”, but he realised early on that ‘seeing is believing’, and when he read about flash powder in 1887, realised its potential to augment his camera. Now he could take indoor shots, so it became the tool he needed to document some of the horrific conditions that he witnessed on a day-to-day basis. He allied himself with two other amateur photographers and the three of them went out into the streets and slums. This culminated in 1890 in a bestselling book ‘How the other half lives’.

From 1870-1900, 9 million immigrants settled in New York. Of these, 1,093,000 inhabited 37,000 tenement buildings. Although there were theoretically governing building regulations, they were frequently ignored, and people were crammed into insanitary, dark, damp, verminous, fever-ridden spaces, often eking out a miserable living by piece-work or just plain begging. Those unable to afford the rent had to doss down where they could, or use the infamous Police Lodgings.

Redemption through education

When his book came out, Riis began giving lectures and showing his photographs. They made such an impression that Theodore Roosevelt, who was an upcoming local politician in those days, took notice, and on Riis’s instigation, closed down some of the worst hostels, demolished some tenements and also built three parks in the slums. Riis wrote a follow-up book called ‘Children of the poor’, which combined pictures with statistics on health, education and crime. This propagated the idea that immigrant children could be helped to become productive citizens by being taught about American democracy.

Riis was a product of his time and, in some of his writing, used racial stereotyping about his subjects that we would find unacceptable today. His often overblown and somewhat florid style was also criticised by his contemporaries. However, looking at his work, there is absolutely no doubt that his heart was in the right place. Indeed, his pictures are not a million miles removed from the work of William Hogarth, whose engravings portrayed the hideously crowded rookeries around St Giles church in London in the 18th century, and Charles Dickens, who so eloquently and sympathetically wrote about the London poor in the Victorian era in his novels.

Changing things for the better

Perhaps it is only fitting that much of the exhibition is under subdued lighting; after all, many of the tenements where Riis took his pictures had little or no illumination. This can sometimes give the pictures a rather odd effect, as the subjects appear slightly startled due to the effects of the flash powder going off.

If you have the time, I would recommend the film clip, which is an excerpt from Riis’ lecture in connection with ‘How the other half lives’. But the crown-jewels are on the floor above, where there is a generous selection of the pictures themselves. They are relatively small (8 x 10 inches usually), but there are also a number of large blow-ups of the best ones.

Photojournalism is now firmly ensconced as part of the mainstream, so it is instructive to be reminded just how ahead of his time Riis was; he showed that a powerful image could stir up the public conscience and change things for the better, and that is a lesson we should not forget.

Note: Although all the labelling and information is in Danish, that should not put you off, as foreign visitors receive a free 40-page booklet with translations of everything into English.